"The Fantastic World of Fellini!"

Amarcord - Symbolism & Philosophy

Symbols & Motifs

The SS Rex

The ocean liner Rex, a real-life pride of Mussolini's regime, symbolizes the grand, hollow promises of Fascism. It represents a dream of American luxury, escape, and modernity that is ultimately an illusory and artificial spectacle.

The entire town rows out in small boats at night into a sea made of plastic sheeting just to catch a glimpse of the magnificent, brilliantly lit ship as it passes. The obvious falseness of the sea and the fleeting, distant nature of the ship underscore the artificiality and unattainability of the Fascist dream it represents.

The Peacock in the Snow

The peacock, spreading its tail feathers in the middle of a snow-covered piazza, represents a moment of inexplicable, mystical beauty amidst the bleakness of winter and the mundane reality of the town. It is a surreal, fleeting image that symbolizes the power of imagination and the sudden, unexpected eruption of wonder in everyday life.

During a rare and heavy snowfall that transforms the town, the Count's peacock appears as if from a dream. The townsfolk, engaged in a snowball fight, stop and marvel at the dazzling, out-of-place beauty of the bird's plumage against the white snow.

Poplar Seeds ('Manine')

The fluffy poplar seeds, called 'manine' (little hands), signify the cyclical nature of life, marking the passage of time and the changing of seasons. They represent the arrival of spring, renewal, and the beginning of the film's one-year narrative cycle.

The film opens with the seeds floating through the air, signaling the end of winter and the start of a new year. The image is repeated at the end of the film, as Gradisca gets married, bringing the story full circle and emphasizing the recurring rhythms of life, death, and new beginnings in the town.

Fog

The dense fog that occasionally envelops the town symbolizes a state of confusion, moral ambiguity, and the blurring of reality and memory. It represents a loss of direction, both for individuals like the grandfather who gets lost in it, and for the town as a whole, lost in the haze of Fascist ideology and their own delusions.

In one memorable scene, Titta's grandfather wanders out into a thick, disorienting fog, unable to recognize his surroundings and feeling as though everything has disappeared. This visual metaphor captures the sense of being lost in a world where clear moral and historical signposts are absent.

Philosophical Questions

What is the nature of memory and its relationship to truth?

"Amarcord" is built on the premise that memory is not a factual record but a creative reconstruction. The film constantly blurs the line between what really happened and what is imagined or embellished in recollection. Characters break the fourth wall to tell stories they admit might not be true, and events take on a dreamlike, surreal quality. Fellini suggests that the emotional truth of a memory—the joy, the fear, the desire—is more important than its factual accuracy. The film asks us to consider if our own past is a fixed history or a story we continually retell and reshape.

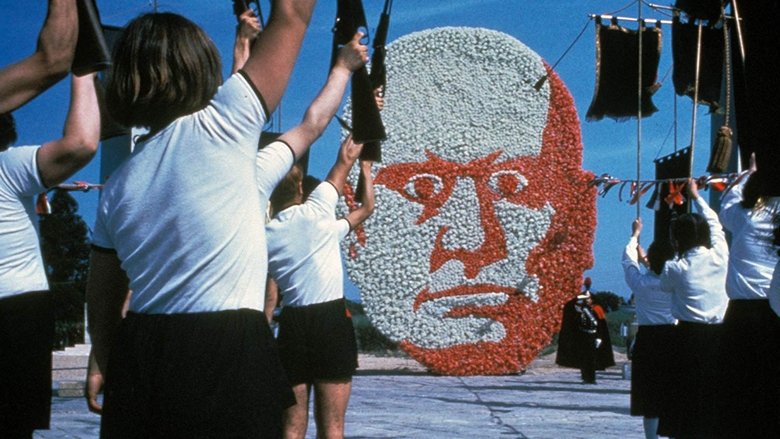

How do collective fantasies and societal immaturity shape political reality?

The film explores how the personal failings and psychological state of a populace can create fertile ground for a political ideology. Fellini posits that Fascism took root in an Italy that was "imprisoned in a perpetual adolescence." The townspeople's obsession with spectacle, their sexual frustrations, their deference to authority, and their preference for comforting myths over difficult realities are shown to be the very characteristics the Fascist regime exploited. The film raises the question of whether people get the governments they deserve and how much individual moral responsibility contributes to national political disasters.

Core Meaning

"Amarcord" is a profound exploration of memory, nostalgia, and the Italian national character. Fellini isn't presenting a factual autobiography but rather a distorted, embellished, and subjective recollection—memory transformed by affection and fantasy. The film's title itself, a blend of Italian words for 'love,' 'heart,' 'remember,' and 'bitter,' encapsulates this complex feeling of a fond, yet poignant, nostalgic evocation.

At its core, the film serves as a critique of what Fellini saw as Italy's "perpetual adolescence." The townspeople, with their foolish sexual fantasies, reliance on ritual, and susceptibility to grand spectacles, are portrayed as being in a state of arrested development. This collective immaturity, Fellini suggests, is what allowed Fascism to take hold. The regime is depicted not as a monstrous evil, but as a ridiculous, theatrical, and clownish extension of the town's own infantilism. Thus, the film is a deeply personal yet universally resonant commentary on how private lives and individual failings can reflect and explain a dark period in a nation's public history.