Amarcord

"The Fantastic World of Fellini!"

Overview

"Amarcord," which translates to "I remember" in the Romagnol dialect, is Federico Fellini's semi-autobiographical reverie of his youth in 1930s Rimini. The film does not follow a conventional plot but instead presents a series of episodic vignettes that unfold over the course of a year, marked by the changing seasons. It begins with the arrival of spring, celebrated by the entire town with a large bonfire.

The narrative loosely centers on Titta Biondi, an adolescent boy, and his eccentric family: his hot-tempered socialist father Aurelio, his long-suffering mother Miranda, his layabout uncle, and his farting grandfather. Through Titta's eyes, we witness the town's daily rituals, its inhabitants' sexual frustrations and fantasies, the pranks of local youths, and the pervasive, often ridiculous, presence of the Fascist regime. Characters are larger-than-life caricatures, from the town beauty Gradisca, who dreams of marrying a film star, to the buxom tobacconist who fuels adolescent desires, and the nymphomaniac Volpina.

The film weaves together moments of broad, bawdy humor with instances of surprising beauty and melancholy. We see the townspeople unite in collective events, like gathering to watch the passage of the magnificent ocean liner, the Rex, or enduring a freak summer snowstorm. These public spectacles are contrasted with intimate family squabbles, schoolboy antics, and personal fantasies, creating a rich tapestry of life in a small Italian town during a turbulent period in history.

Core Meaning

"Amarcord" is a profound exploration of memory, nostalgia, and the Italian national character. Fellini isn't presenting a factual autobiography but rather a distorted, embellished, and subjective recollection—memory transformed by affection and fantasy. The film's title itself, a blend of Italian words for 'love,' 'heart,' 'remember,' and 'bitter,' encapsulates this complex feeling of a fond, yet poignant, nostalgic evocation.

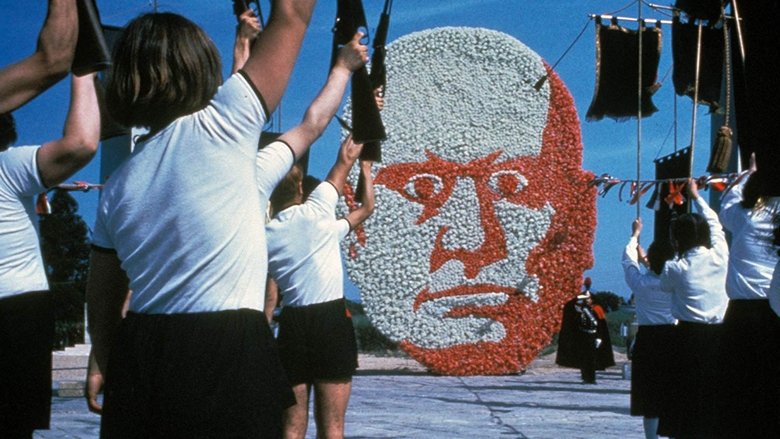

At its core, the film serves as a critique of what Fellini saw as Italy's "perpetual adolescence." The townspeople, with their foolish sexual fantasies, reliance on ritual, and susceptibility to grand spectacles, are portrayed as being in a state of arrested development. This collective immaturity, Fellini suggests, is what allowed Fascism to take hold. The regime is depicted not as a monstrous evil, but as a ridiculous, theatrical, and clownish extension of the town's own infantilism. Thus, the film is a deeply personal yet universally resonant commentary on how private lives and individual failings can reflect and explain a dark period in a nation's public history.

Thematic DNA

Memory and Nostalgia

The entire film is structured as a collection of memories, but they are subjective and dreamlike rather than historically accurate. The title "Amarcord" itself means "I remember" in the local dialect. Fellini recreates his hometown not as it was, but as he remembers it, filled with exaggerated characters and fantastical events. This creates a powerful sense of nostalgia, a bittersweet yearning for a past that is both cherished and critiqued. The film suggests that memory is not a perfect record but a creative act of reconstruction.

Adolescence and Coming-of-Age

The film explores the turbulent world of adolescence through the character of Titta and his friends. Their experiences are defined by burgeoning sexual curiosity, awkward encounters, and rebellion against authority figures like teachers and priests. The obsession with women, from the glamorous Gradisca to the buxom tobacconist, is a central comedic and thematic element. Fellini links this individual, adolescent state to a national one, suggesting that Fascist Italy was trapped in a state of "eternal adolescence," unable to achieve genuine moral responsibility.

Critique of Fascism and Authority

"Amarcord" presents a scathing satire of Italian Fascism. Rather than depicting fascists as monstrous villains, Fellini portrays them as pathetic, posturing clowns engaged in ridiculous parades and gymnastic exercises. The regime's power is shown as a form of theatrical, puppet-like control that exploits the townspeople's immaturity and love of spectacle. The film critiques not just the political regime but also other authority figures, particularly those of the Catholic Church, who are mocked for their hypocrisy and inability to guide the town's moral development.

Community and Ritual

The film is as much a portrait of a town as it is of any individual. The life of the community is structured around seasons and rituals, from the spring bonfire that opens the film to the collective boat trip to see the ocean liner Rex. These events bring the eccentric cast of characters together, highlighting their shared dreams, absurdities, and sense of belonging. Fellini uses these communal set-pieces to examine the social fabric and the ways in which ritual can both unite people and reinforce their collective delusions.

Character Analysis

Titta Biondi

Bruno Zanin

Motivation

Titta's primary motivations are quintessentially adolescent: to satisfy his burgeoning sexual curiosity, to assert his independence from his family, and to find his place among his peers. He is driven by his fantasies about the town's women, especially Gradisca and the tobacconist.

Character Arc

Titta does not have a traditional character arc of profound change; rather, he is an observer and participant through whom the audience experiences the town's life over a year. His journey is one of sentimental education, navigating the confusing worlds of sexuality, family, and politics. He moves from schoolboy pranks and communal masturbation to more direct, albeit clumsy, encounters with female sexuality, and witnesses the harsh reality of Fascism when his father is interrogated. His mother's death marks a significant moment of maturation and confrontation with loss, pushing him from adolescence toward a more somber understanding of life.

Gradisca

Magali Noël

Motivation

Gradisca is motivated by a deep desire for a grand, cinematic romance and to escape the provincial limitations of the town. She longs for a husband, a family, and, most importantly, affection, which she feels she has in abundance but no one to give it to.

Character Arc

Gradisca begins the film as the town's primary sexual fantasy, a glamorous hairdresser who walks with an air of unattainable allure. She dreams of a grand, romantic love, fantasizing about film stars like Gary Cooper. Her arc is one of disillusionment and compromise. As the year progresses, her fantasies give way to the reality of her aging. Her story culminates in her marriage not to a movie star, but to a Carabiniere (a state police officer), a practical match that signifies the end of her youthful dreams and an acceptance of a more mundane life. Her departure marks the end of an era for the town's dreamers.

Aurelio Biondi

Armando Brancia

Motivation

Aurelio is motivated by the desire to provide for his family and to maintain his dignity and anti-fascist principles in a hostile political environment. His constant shouting and frustration stem from his inability to control his chaotic household or the oppressive political forces around him.

Character Arc

Aurelio is a volatile but ultimately loving father and husband, a construction worker whose socialist beliefs put him at odds with the Fascist regime. His arc is not one of transformation but of endurance. He rails against his family, the government, and life's frustrations in theatrical outbursts. A key moment of his story is his arrest and humiliation by Fascist thugs, who force-feed him castor oil—a brutal reality that pierces the film's comedic tone. His character represents the powerless frustration of the common man under an oppressive regime.

Miranda Biondi

Pupella Maggio

Motivation

Miranda's motivation is the well-being of her family. She is driven by a deep-seated anxiety and love for her husband and children, which manifests as constant fretting, complaining, and emotional outbursts designed to keep them in line and safe.

Character Arc

Miranda is the emotional core of the Biondi family, a histrionic and perpetually worried mother who holds the chaotic household together. She constantly threatens to kill herself over her family's antics but displays deep affection. Her arc is the most tragic in the film. After a year of enduring the family's madness, she falls ill and dies unexpectedly. Her death brings a sudden and profound sense of loss, shattering the film's carnivalesque atmosphere and forcing the family, particularly Titta, to confront a stark and painful reality.

Symbols & Motifs

The SS Rex

The ocean liner Rex, a real-life pride of Mussolini's regime, symbolizes the grand, hollow promises of Fascism. It represents a dream of American luxury, escape, and modernity that is ultimately an illusory and artificial spectacle.

The entire town rows out in small boats at night into a sea made of plastic sheeting just to catch a glimpse of the magnificent, brilliantly lit ship as it passes. The obvious falseness of the sea and the fleeting, distant nature of the ship underscore the artificiality and unattainability of the Fascist dream it represents.

The Peacock in the Snow

The peacock, spreading its tail feathers in the middle of a snow-covered piazza, represents a moment of inexplicable, mystical beauty amidst the bleakness of winter and the mundane reality of the town. It is a surreal, fleeting image that symbolizes the power of imagination and the sudden, unexpected eruption of wonder in everyday life.

During a rare and heavy snowfall that transforms the town, the Count's peacock appears as if from a dream. The townsfolk, engaged in a snowball fight, stop and marvel at the dazzling, out-of-place beauty of the bird's plumage against the white snow.

Poplar Seeds ('Manine')

The fluffy poplar seeds, called 'manine' (little hands), signify the cyclical nature of life, marking the passage of time and the changing of seasons. They represent the arrival of spring, renewal, and the beginning of the film's one-year narrative cycle.

The film opens with the seeds floating through the air, signaling the end of winter and the start of a new year. The image is repeated at the end of the film, as Gradisca gets married, bringing the story full circle and emphasizing the recurring rhythms of life, death, and new beginnings in the town.

Fog

The dense fog that occasionally envelops the town symbolizes a state of confusion, moral ambiguity, and the blurring of reality and memory. It represents a loss of direction, both for individuals like the grandfather who gets lost in it, and for the town as a whole, lost in the haze of Fascist ideology and their own delusions.

In one memorable scene, Titta's grandfather wanders out into a thick, disorienting fog, unable to recognize his surroundings and feeling as though everything has disappeared. This visual metaphor captures the sense of being lost in a world where clear moral and historical signposts are absent.

Memorable Quotes

Voglio una donna!

— Uncle Teo

Context:

The Biondi family takes Titta's Uncle Teo out from the mental asylum for a day's picnic in the countryside. During the outing, Teo suddenly climbs a tall tree and refuses to come down, repeatedly shouting this line to the sky, much to the family's exasperation and embarrassment.

Meaning:

Meaning "I want a woman!", this desperate, repeated cry from the top of a tree encapsulates the film's central theme of rampant, unfulfilled sexual desire and frustration. It is both hilarious in its absurdity and deeply pathetic, symbolizing the infantile and primal urges that characterize many of the town's male inhabitants.

Se la morte è così, non mi piace per niente. È sparito tutto. La gente, gli alberi, gli uccelli...

— Grandpa

Context:

Titta's grandfather wanders away from the house and gets completely lost in a thick, dense fog that has descended upon the town. Unable to see or recognize anything, he speaks these lines aloud, equating his sensory deprivation and isolation with the nothingness of death.

Meaning:

Meaning "If death is like this, I don't think much of it. Everything's gone. People, trees, birds...", this quote reflects a moment of profound existential disorientation. It blurs the line between a physical state (being lost in the fog) and a metaphysical one (contemplating death), highlighting the film's themes of confusion and the search for meaning in a world where familiar landmarks have disappeared.

Philosophical Questions

What is the nature of memory and its relationship to truth?

"Amarcord" is built on the premise that memory is not a factual record but a creative reconstruction. The film constantly blurs the line between what really happened and what is imagined or embellished in recollection. Characters break the fourth wall to tell stories they admit might not be true, and events take on a dreamlike, surreal quality. Fellini suggests that the emotional truth of a memory—the joy, the fear, the desire—is more important than its factual accuracy. The film asks us to consider if our own past is a fixed history or a story we continually retell and reshape.

How do collective fantasies and societal immaturity shape political reality?

The film explores how the personal failings and psychological state of a populace can create fertile ground for a political ideology. Fellini posits that Fascism took root in an Italy that was "imprisoned in a perpetual adolescence." The townspeople's obsession with spectacle, their sexual frustrations, their deference to authority, and their preference for comforting myths over difficult realities are shown to be the very characteristics the Fascist regime exploited. The film raises the question of whether people get the governments they deserve and how much individual moral responsibility contributes to national political disasters.

Alternative Interpretations

While the dominant interpretation of "Amarcord" sees it as a satirical critique of Fascism rooted in national immaturity, alternative readings exist. Some critics view the film less as a political statement and more as a purely personal, lyrical poem about the nature of memory itself. In this light, the political elements are secondary to the film's primary focus on the way the past is distorted, romanticized, and kept alive through subjective recollection. The film becomes a universal story about anyone's relationship with their own childhood, where memories are a blend of truth and fantasy.

Another perspective downplays the critique and emphasizes the warmth and affection Fellini has for his characters and his hometown. Foster Hirsch, for example, found the film to be Fellini's "warmest, most subdued film," though he missed the director's grander flourishes. From this angle, the film is less a scathing satire and more of a bittersweet love letter to a vanished world. The grotesqueries and absurdities are not just symbols of a flawed society but are also embraced with a genuine, if complicated, fondness for the vitality and humanity of the people, however flawed they may be.

Cultural Impact

"Amarcord" is widely regarded as one of Federico Fellini's last great masterpieces and a quintessential example of his unique cinematic style. Released in 1973, it came at a time when Italy was grappling with its Fascist past. The film offered a complex cultural interpretation of the period, not through a direct political denunciation, but through a satirical and psychological exploration of the national character that allowed such a regime to flourish. Fellini's portrayal of fascism as an extension of an immature, adolescent mindset was a groundbreaking and influential perspective.

Critically, the film was a major success, winning the 1975 Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film and earning nominations for Director and Screenplay. Roger Ebert hailed it as "not only a great movie, it's a great joy to see," praising its universal accessibility. While some contemporary critics found it less vigorous than his earlier works, it has since been cemented as one of his most beloved films. Its influence can be seen in countless nostalgic, magical-realist depictions of small-town life in cinema. The film's visual language, with its carnivalesque atmosphere, eccentric caricatures, and blend of the mundane with the fantastical, has become synonymous with the term "Felliniesque." "Amarcord" permeated popular culture to the extent that its title became a neologism in the Italian language, signifying a fond, nostalgic memory.

Audience Reception

Audiences have generally responded to "Amarcord" with great affection, making it one of Fellini's most accessible and beloved films. Viewers praise its vibrant humor, warmth, and the universal themes of youth, memory, and community. Many are captivated by the gallery of eccentric and unforgettable characters, finding them both hilarious and poignantly human. The film's visual splendor and Nino Rota's evocative score are consistently highlighted as key elements of its enduring appeal. On Rotten Tomatoes, it holds a high approval rating, with the consensus calling it "Ribald, sweet, and sentimental... a larger-than-life journey."

Points of criticism are less common but do exist. Some viewers, particularly those less familiar with Fellini's style, can find the episodic, plotless structure to be meandering or undisciplined. The film's humor, which is often bawdy and grotesque, may not appeal to all tastes. A few critics at the time of its release felt it was a "safer" and less artistically vigorous work compared to Fellini's earlier masterpieces like "8 ½".

Interesting Facts

- The title "Amarcord" is a univerbation from the dialect of Fellini's native Romagna, meaning "a m'arcôrd" or "I remember." Fellini also suggested it was a fusion of the Italian words for 'love' (amare), 'heart' (cuore), 'remember' (ricordare), and 'bitter' (amaro).

- The film is semi-autobiographical, but Fellini took many liberties. The central character Titta is based on Fellini's childhood friend, Luigi 'Titta' Benzi, and the family depicted is Benzi's, not Fellini's.

- Despite being set in Fellini's seaside hometown of Rimini, the entire film was shot on meticulously constructed sets at the Cinecittà studios in Rome, including the town square and the ocean.

- "Amarcord" won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1975, marking Fellini's fourth win in that category.

- The famous scene with the SS Rex passing by at sea was created using a large-scale model, and the sea itself was made of black plastic sheeting manipulated by stagehands.

- The voluptuous tobacconist was played by Maria Antonietta Beluzzi, a non-professional actress who was discovered by Fellini. Her casting perfectly embodied Fellini's preference for characters with larger-than-life physical attributes.

- Many of the film's characters and events, while exaggerated, were drawn from real people and legends from Fellini's youth in Rimini.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!