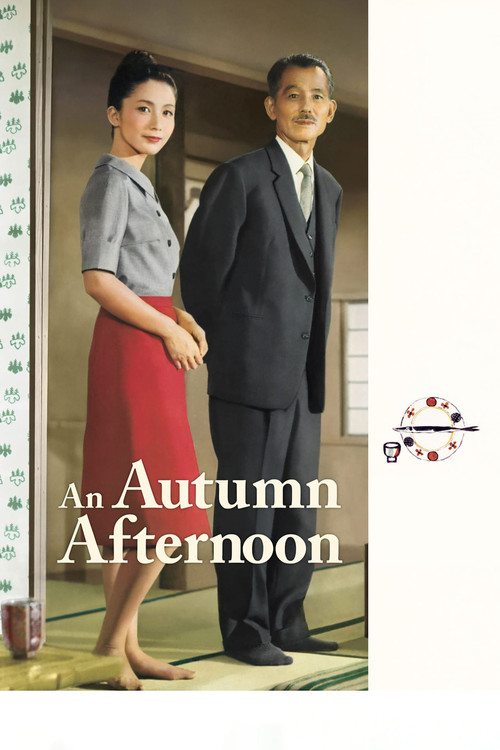

秋刀魚の味

An Autumn Afternoon - Symbolism & Philosophy

Symbols & Motifs

The Taste of Sanma (Mackerel Pike)

The original Japanese title, Sanma no Aji, translates to "The Taste of Sanma." Sanma is a fish associated with autumn, and its taste is considered somewhat bitter. This symbolizes the bittersweet feelings Hirayama experiences—the happiness for his daughter's marriage mixed with the sadness of his impending loneliness, mirroring the melancholy of the autumn season of life.

While the fish itself never appears in the film, the title itself sets the entire emotional tone. It's an abstract symbol that permeates the film's atmosphere, representing the complex, bittersweet emotions tied to aging, family, and letting go.

Empty Spaces (Pillow Shots)

Ozu frequently uses shots of empty rooms, corridors, and objects after characters have left the frame. This technique, known as a "pillow shot," symbolizes absence, loss, and the quiet loneliness that pervades the characters' lives. These empty spaces are filled with the emotional residue of the events that have just transpired.

This is most poignant at the end of the film. After Michiko's wedding, Ozu repeatedly cuts to shots of the now-empty rooms of the Hirayama household. Hirayama is seen in his kitchen, alone and hunched over. The lingering shots of the empty living room where Michiko once was powerfully convey the void she has left behind.

The Color Red

In his later color films, Ozu strategically used the color red to draw the viewer's attention and often to signify a point of emotional intensity within his otherwise muted color palettes. It acts as a visual accent that breaks the calm surface of the scene.

Ozu places red objects—a teapot, a sign, a piece of clothing—in otherwise neutrally toned scenes. For example, a bright red lampshade or container in the bar or a red sweater. These splashes of color punctuate the visual composition and subtly heighten the emotional undercurrent of the moment.

The 'Warship March'

The military tune Hirayama hums and sings at the end is the "Gunkan Māchi," a famous Imperial Japanese Navy march. It symbolizes a retreat into nostalgia and memory as a coping mechanism for his present loneliness. It juxtaposes a song of nationalistic, youthful fervor with a moment of profound personal solitude in postwar Japan.

After Michiko's wedding, a drunk and melancholy Hirayama is alone in his now-quiet house. He drunkenly sings snatches of the march, a sound from his past as a naval officer, underscoring his final, lonely state.

Philosophical Questions

Is selfless action truly selfless if it leads to one's own suffering?

The film explores this through Hirayama's central decision. He acts out of a selfless love for his daughter, believing he is securing her happiness. However, this action directly leads to his own profound loneliness. Ozu doesn't provide an easy answer. He presents the action as both necessary and heartbreaking, questioning the very nature of parental sacrifice. The film suggests that in this traditional framework, there is no other choice, and the resulting sadness must be borne with quiet dignity.

How does one reconcile personal happiness with societal and familial duty?

This question is embodied by Michiko. She has a hint of a personal desire—an unspoken affection for Miura—but this is quickly subsumed by her duty as a daughter to accept the marriage her father arranges. The film meticulously portrays a world where personal desire is secondary to the smooth functioning of the family and society. It asks whether true contentment can be found in fulfilling one's prescribed role, or if this fulfillment always comes with a sense of quiet resignation and lost opportunity.

Can we ever escape the cycle of life and the loneliness it inevitably brings?

The film presents life as a repeating cycle: parents raise children, the children leave to start their own families, and the parents are left alone. Hirayama sees his own future in the lonely figure of his old teacher. He knows what awaits him, yet he pushes his daughter along the same path. Ozu's calm, cyclical narrative style suggests that this is an immutable law of nature. The film doesn't offer an escape but instead advocates for a form of acceptance, finding a bittersweet beauty in this inevitable, sorrowful process.

Core Meaning

The core meaning of "An Autumn Afternoon" revolves around the themes of change, acceptance, and the bittersweet nature of family life. Director Yasujirō Ozu poignantly explores the quiet melancholy of a father who, out of love and a sense of duty, arranges his daughter's marriage, thereby ensuring her future happiness at the cost of his own companionship. The film is a meditation on the cyclical nature of life—children growing up and leaving the nest—and the quiet dignity in accepting loneliness as an inevitable part of life's progression. It suggests that true parental love involves letting go, even when it brings personal sadness. The "taste of sanma" (the original Japanese title, referring to the Pacific saury fish) evokes a sense of autumn and a corresponding bitterness, reflecting the father's mixed feelings about his daughter's departure and the onset of his own later years.