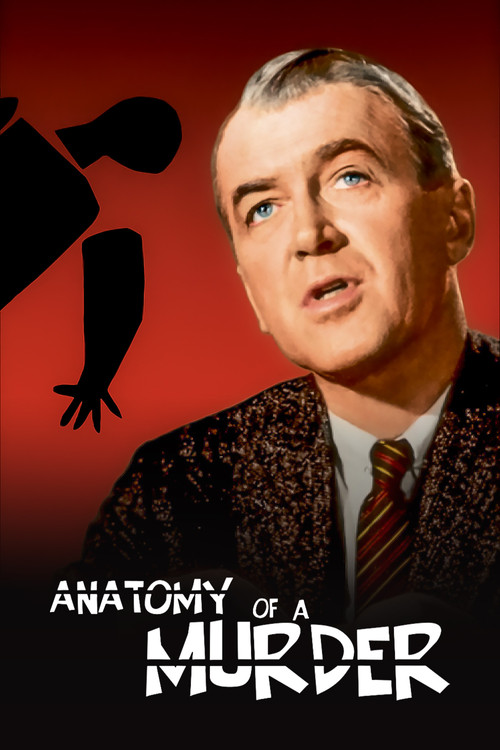

"No search of human emotions has ever probed so deeply, so truthfully as… Anatomy of a Murder."

Anatomy of a Murder - Ending Explained

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

The central twist of "Anatomy of a Murder" is not a last-minute revelation but the gradual and unsettling realization that the entire defense may be a carefully constructed lie. Defense attorney Paul Biegler subtly coaches his client, Lt. Manion, on the concept of "irresistible impulse," a form of temporary insanity defense. Manion, who initially claims to have no memory of the murder, conveniently adopts this as his official story. The brilliance of the film lies in its ambiguity; it never explicitly confirms whether Manion was genuinely insane or if he was coached into a phony story.

During the trial, the prosecution, led by Claude Dancer, attempts to paint Laura Manion as a promiscuous woman who may have consented to a sexual encounter with the victim, Barney Quill. A key piece of evidence, Laura's missing panties, becomes a central point of contention. The case takes a surprising turn when it is revealed that the innkeeper Mary Pilant, whom Dancer had accused of being Quill's mistress, is actually his illegitimate daughter. This revelation discredits the prosecution's theory about her motives.

Ultimately, the jury finds Lt. Manion not guilty by reason of insanity. The final, cynical twist comes after the trial. Biegler and his partner Parnell go to collect their fee from the Manions, only to find they have skipped town. Manion has left a note for Biegler, stating that he had to leave due to an "irresistible impulse," mockingly throwing the very legal defense that acquitted him back in his lawyer's face. This ending strongly implies that Manion was guilty and manipulated the legal system to get away with murder, leaving Biegler and the audience to grapple with the unsettling nature of the verdict. It becomes clear that Laura was likely aware of the deception, and her earlier fear of her husband's temper suggests a more complex and potentially abusive relationship.

Alternative Interpretations

A significant alternative interpretation revolves around Laura Manion's role in the events. While the primary narrative presents her as a potential rape victim, some analyses suggest she may not have been raped at all. This perspective posits that she might have been having an affair with Barney Quill. When her violently jealous husband, Lt. Manion, discovered the affair, he beat her (explaining her injuries) and then murdered Quill in a jealous rage. In this reading, the entire rape story is a fabrication concocted by Laura and her husband to create a legal defense. This interpretation views Laura not as a victim, but as a manipulative femme fatale who orchestrates the entire legal defense to save her husband.

Another interpretation focuses on the character of Paul Biegler. While he is the film's protagonist, he can also be seen as a monstrous figure whose primary interest is not in justice, but in winning a high-profile case. From this viewpoint, Biegler knowingly helps a guilty man escape conviction by carefully feeding him the "irresistible impulse" defense. The film's "happy ending," where Biegler and McCarthy decide to restart their practice, is therefore seen as deeply cynical, celebrating a victory for legal maneuvering over actual justice. This reading emphasizes the film's critique of a legal system where the truth is secondary to the skill of the lawyers.