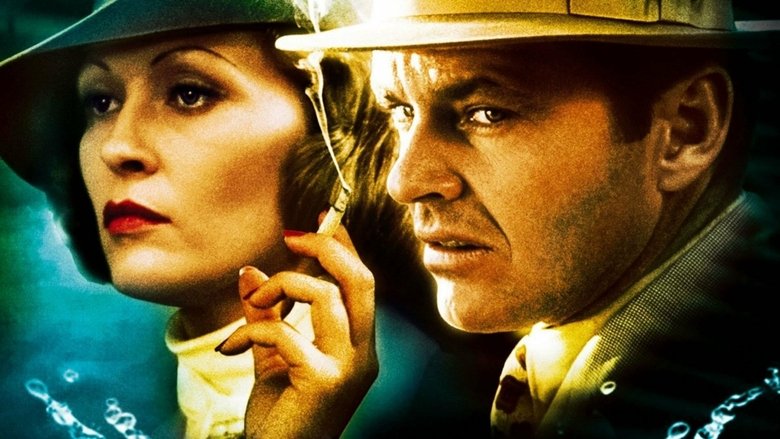

"You get tough. You get tender. You get close to each other. Maybe you even get close to the truth."

Chinatown - Symbolism & Philosophy

Symbols & Motifs

Water

Water symbolizes life, power, and the future. In the drought-stricken setting of Los Angeles, control over water is tantamount to control over the city's growth and prosperity. Noah Cross's manipulation of this vital resource for profit highlights his god-like ambition and moral corruption. The dumping of fresh water into the ocean is a powerful image of this corruption—a wasteful, unnatural act that serves a greedy agenda.

The entire plot is driven by the conspiracy to control Los Angeles' water. The investigation leads Jake to reservoirs, dry riverbeds, and orange groves. Hollis Mulwray, who opposes the new dam, is found drowned in a reservoir, a bitter irony that underscores the symbol's significance.

The Flaw in the Iris / Broken Glasses

These symbols represent flawed perception and the inability to see the full truth. Evelyn has a visible flaw in her iris, which Gittes notices. This physical imperfection mirrors her fractured emotional state and the hidden truths she conceals. Similarly, the broken bifocals found in the pond are a crucial clue that ultimately points to Noah Cross, a man whose vision of the future is monstrously distorted. The recurring motif of lenses—cameras, binoculars, cracked glasses—emphasizes the theme of obscured or partial vision.

Gittes first observes the flaw in Evelyn's eye when they meet. He later finds the bifocals in the saltwater pond at the Mulwray residence. The glasses do not belong to Hollis, which becomes a key point in Gittes's investigation, eventually leading him to confront Cross.

Gittes's Bandaged Nose

The prominent bandage on Jake's nose for much of the film symbolizes his vulnerability and the painful consequences of being "nosy." It's a constant, visible reminder that his investigation has made him a target and that he is in over his head. The injury, inflicted by a thug played by Polanski himself, serves as a direct warning to stop digging into matters that powerful people want to keep hidden. It also represents a form of impotence, a mark of his failure to command the situation.

Early in his investigation, while snooping around a reservoir at night, Gittes is caught by thugs. One of them cuts his nostril, telling him, "You're a very nosy fellow, kitty cat." Gittes wears a conspicuous bandage for the majority of the film, a visual manifestation of the danger he is in.

Chinatown

Chinatown is not just a location but a powerful metaphor for the unknowable, the corrupt, and the futility of good intentions. It represents a world with its own set of rules where outsiders are powerless and attempts to impose order or justice are bound to fail, often with tragic consequences. It symbolizes a state of mind, a place of past trauma for Gittes, and the ultimate heart of darkness where evil triumphs.

Gittes reveals he used to be a cop in Chinatown and his past experience there was tragic. He tells Evelyn he was trying to "save" a woman, but ended up "hurting her." The film's climax is deliberately set in Chinatown, bringing Gittes's past and present failures full circle as his attempts to save Evelyn lead directly to her death. The final line, "Forget it, Jake. It's Chinatown," cements the location's symbolic meaning.

Philosophical Questions

Can an individual truly effect change in a systemically corrupt world?

The film explores this question through the character of Jake Gittes. Despite his skills as an investigator and his growing determination, every step he takes to expose the truth and protect the innocent results in disaster. The film's bleak conclusion, where the villain wins completely and the heroine is killed, provides a deeply pessimistic answer. It suggests that individual action is futile against entrenched, systemic corruption. The powerful, like Noah Cross, own the institutions meant to provide justice, rendering any single person's efforts meaningless. The final line, "Forget it, Jake. It's Chinatown," is the ultimate concession to this grim reality.

What is the nature of evil?

"Chinatown" presents a profound and disturbing portrait of evil through Noah Cross. He is not a one-dimensional villain but a charming, intelligent, and powerful man who commits heinous acts without remorse. The film explores evil not as a simple aberration but as a fundamental aspect of human potential. Cross's assertion that anyone is "capable of anything" given the right circumstances challenges the audience's moral certainty. The film suggests that the most terrifying evil is not chaotic but rational and calculating, born from an insatiable desire for power and control over the future.

Is it better to uncover a painful truth or to leave secrets buried?

Gittes's relentless pursuit of the truth drives the narrative, but the film constantly questions the virtue of this pursuit. Uncovering the conspiracy leads to multiple deaths, and forcing the truth from Evelyn about Katherine's parentage leads directly to the tragic climax. The film seems to argue that some truths are so monstrous that their revelation causes more destruction than their concealment. Gittes's failure lies in his inability to comprehend the depth of the depravity he is dealing with until it is too late. He operates under the detective's assumption that truth brings clarity and justice, but in the world of "Chinatown," it only brings pain and death.

Core Meaning

At its heart, "Chinatown" is a cynical exploration of the pervasiveness of corruption and the powerlessness of the individual in the face of systemic evil. Director Roman Polanski and writer Robert Towne present a world where wealth and influence allow the powerful to operate above the law, manipulating vital resources like water for personal gain. The film suggests that even the most determined efforts to uncover the truth and achieve justice are ultimately futile. The title itself becomes a metaphor for a state of moral confusion and helplessness, a place where good intentions lead to tragic outcomes, and the only sensible advice is to "do as little as possible." Ultimately, the film posits that the past is inescapable and that some secrets are so monstrous they corrupt everything they touch, leaving no room for heroism or redemption.