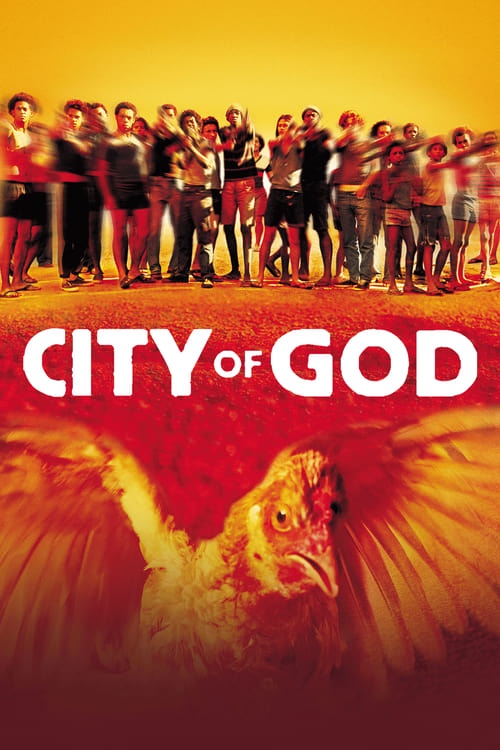

Cidade de Deus

"If you run, the beast catches you; if you stay, the beast eats you."

City of God - Ending Explained

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

The narrative of "City of God" is framed by a tense standoff involving a runaway chicken, which is revealed in the third act to be the catalyst for the final, bloody confrontation between the gangs of Li'l Zé and Knockout Ned. A key twist earlier in the film involves the massacre at the motel. Initially, the event is portrayed as a robbery by the Tender Trio, but a later flashback reveals it was orchestrated by the child Li'l Dice (a young Li'l Zé), who murders everyone inside, establishing his psychopathic nature from a very young age.

The central tragedy of the film is the death of Benny. Seeking to leave the life of crime, Benny is accidentally shot and killed at his own farewell party by Blacky, who was actually aiming for Li'l Zé. Benny's death is the crucial turning point; it dissolves the last vestige of moderation in Li'l Zé's crew and directly triggers the all-out war with Carrot and Knockout Ned, as Li'l Zé uses the event as a pretext to eliminate his rivals.

The ending provides a devastating confirmation of the film's central theme: the inescapable cycle of violence. After the climactic gunfight, the police arrest Li'l Zé but are bribed to let him go. Immediately upon his release, he is surrounded and murdered by the "Runts," a gang of young children seeking revenge and wanting to take over his turf. The final scene shows the Runts walking through the favela, making a list of dealers they plan to kill to consolidate their new power. They are the new Li'l Dices, destined to become the new Li'l Zés. Rocket achieves his personal dream of escape by getting a job at a newspaper, but his success is juxtaposed with the grim reality that nothing has fundamentally changed in the City of God.

Alternative Interpretations

While the dominant interpretation of "City of God" sees Rocket's escape as a hopeful conclusion, an alternative reading views it with more cynicism. This perspective argues that Rocket's success is not a true escape but a form of complicity. He becomes a successful photographer by profiting from the violence and tragedy of his own community, selling its brutal reality to the outside world. His final choice to photograph Li'l Zé's body for the newspaper, rather than the corrupt police, can be seen as a pragmatic, self-serving decision rather than a purely moral one. From this viewpoint, the film offers a bleaker commentary on the media's role in sensationalizing poverty and violence, suggesting that even the 'way out' is fraught with moral compromise.

Another interpretation focuses less on the individual journeys and more on the favela as a character itself—a living, breathing organism governed by its own laws. In this view, the human characters are merely transient cells within this larger body. Their rise and fall are less about personal choice and more about the inevitable, violent metabolism of the slum. Li'l Zé's death and the immediate rise of the Runts are not just a cycle of violence but the favela's natural process of regeneration and self-perpetuation. The ending is not bittersweet but simply a statement of fact: the City of God endures, and its nature remains unchanged, regardless of who holds power within it.