生きる

"A big story of a little man which will grip your soul..."

Ikiru - Ending Explained

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

The narrative structure of "Ikiru" is one of its most brilliant and revealing aspects. The film is divided into two distinct parts. The first part follows Kanji Watanabe chronologically from his cancer diagnosis to his discovery of a new purpose in building a park. Just as he finds his resolve, the narrator announces that Watanabe died five months ago, and the film abruptly shifts to his funeral wake.

The entire second half of the film reconstructs Watanabe's final months through the fragmented, biased, and slowly dawning recollections of his family and co-workers. Initially, they are clueless, speculating that he was involved with a young woman or simply behaving erratically. As they drink and talk, the truth of his single-minded, heroic effort to build the park is revealed through a series of flashbacks, pieced together by their combined memories and testimony from the mothers he helped. We learn that he battled the bureaucracy, faced down gangsters, and endured pain with quiet determination, all to see the park built.

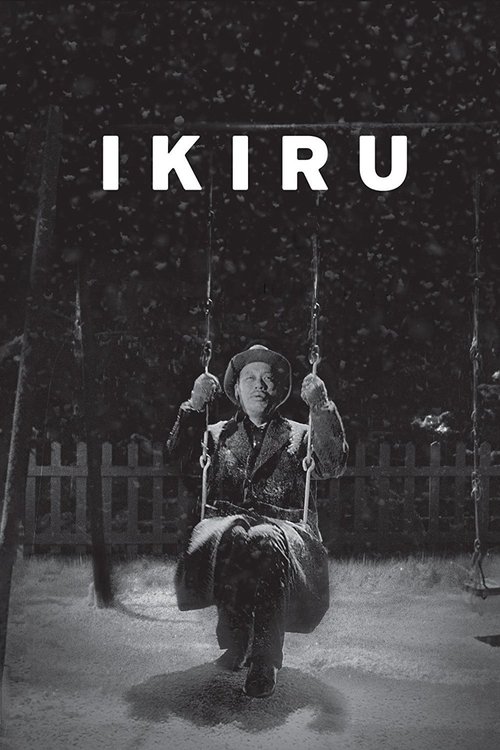

The ultimate hidden meaning is revealed in the final flashback, recounted by a policeman: Watanabe's death was not a sad, lonely event. He died peacefully in the park he created, sitting on a swing in the snow, gently singing "Gondola no Uta." This final image recasts his entire struggle as a triumph. The devastating irony is that after this night of emotional revelation, his colleagues, who had drunkenly vowed to change their ways, return to their desks and continue the same meaningless bureaucratic shuffle, demonstrating that his personal redemption did not reform the system.

Alternative Interpretations

While the dominant interpretation of "Ikiru" is one of hopeful redemption, some critics offer a more cynical reading of the ending. This perspective focuses on Watanabe's colleagues at his wake. After spending the night piecing together his story and tearfully vowing to live with the same purpose and integrity, they return to work the very next day and immediately fall back into their old, mindless bureaucratic routines.

This interpretation suggests that Watanabe's transformation was a singular, isolated event that ultimately failed to inspire lasting change in the system he fought against. His heroic act, therefore, might be seen not as a triumph that redeems society, but as a beautiful, tragic exception that proves the rule of systemic inertia. The final shot of another bureaucrat walking past the park, barely giving it a glance, could support this view—that Watanabe's legacy is cherished by the community but ignored by the very people who should have learned from it. The film, from this angle, is less a story of universal hope and more a somber reflection on the immense difficulty of effecting genuine change.