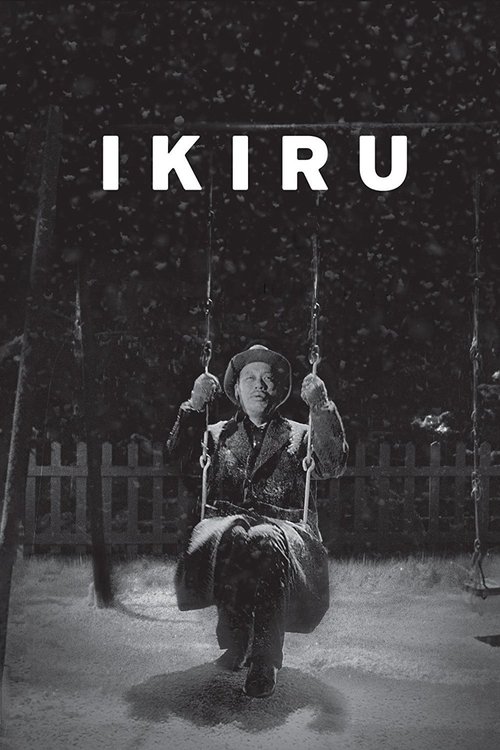

Ikiru

生きる

"A big story of a little man which will grip your soul..."

Overview

"Ikiru" (生きる, "To Live") is a 1952 masterpiece by director Akira Kurosawa. The film follows Kanji Watanabe, a veteran civil servant who has spent thirty years in a monotonous bureaucratic post. His life is a dull routine of stamping papers, earning him the nickname "The Mummy" from his subordinates. When he is diagnosed with terminal stomach cancer and given less than a year to live, he is thrown into a profound existential crisis.

Forced to confront the emptiness of his past, Watanabe embarks on a desperate search for meaning. He initially explores Tokyo's nightlife, seeking pleasure in hedonism, but finds it hollow. His journey then leads him to an unexpected friendship with a cheerful young woman, a former colleague, whose simple zest for life inspires him. This encounter catalyzes a transformation, pushing Watanabe to find a purpose in his final months by championing a cause he once ignored: converting a hazardous cesspool into a children's playground.

Core Meaning

The core message of "Ikiru" is a powerful meditation on the meaning of life and the inevitability of death. Kurosawa suggests that a truly fulfilled life is not measured by longevity or material possessions, but by purposeful action and selfless contribution to the well-being of others. The film argues that confronting one's own mortality can be a catalyst for profound personal transformation, awakening an individual from a passive existence to a life of active engagement and meaning. Watanabe's final act of creating a park demonstrates that even one small, altruistic achievement can redeem a lifetime of monotony and provide a lasting, positive legacy.

Thematic DNA

The Search for Meaning

This is the central theme, triggered by Watanabe's terminal diagnosis. Having lived a life devoid of purpose, he is forced to ask what it truly means "to live." His journey through nightlife proves unfulfilling, showing that meaning is not found in fleeting pleasures. Ultimately, he discovers that purpose lies in altruistic action—creating something tangible and beneficial for the next generation, thus giving his remaining days profound significance.

Mortality and the Human Condition

The film is a deep exploration of the existential crisis that arises from the awareness of death. Watanabe's cancer is the catalyst that forces him to examine the "unexamined life." Kurosawa posits that it is only when faced with the certainty of death that one can truly appreciate the beauty and potential of life. This confrontation with mortality transforms Watanabe from a passive "mummy" into a man of determined action.

Critique of Bureaucracy

"Ikiru" serves as a sharp critique of the stifling nature of post-war Japanese bureaucracy. Watanabe's office is depicted as a place of meaningless routine and inaction, where public servants are more concerned with procedure than with serving the public. Watanabe's heroic act involves breaking through this very red tape, demonstrating that individual will and humanism can overcome institutional inertia. The failure of his colleagues to change after his death underscores the deep-seated nature of this systemic problem.

Family and Generational Disconnect

The film portrays a decaying family life in modern Japan. Watanabe's relationship with his son, Mitsuo, is strained and distant. Mitsuo and his wife seem more concerned with their inheritance than with Watanabe's well-being, highlighting a failure of communication and empathy between generations. This personal isolation further fuels Watanabe's quest for connection and meaning outside his own home.

Character Analysis

Kanji Watanabe

Takashi Shimura

Motivation

Initially, his motivation is a desperate, fear-driven need to feel alive and find meaning before he dies. This evolves into a genuine, altruistic desire to create something positive and lasting for others, specifically the children of his community.

Character Arc

Watanabe begins as a passive, lifeless bureaucrat, nicknamed "The Mummy," who has been spiritually dead for decades. His terminal cancer diagnosis acts as a catalyst, shocking him out of his inertia. He goes through stages of despair, hedonism, and vicarious living before finding his own authentic purpose. He transforms into a determined, single-minded activist who, through an act of selfless creation, achieves a state of profound peace and fulfillment before his death, leaving behind a meaningful legacy.

Toyo Odagiri

Miki Odagiri

Motivation

Her motivation is simple: to escape the monotony of bureaucracy and find a job that brings her happiness and a sense of purpose, no matter how small.

Character Arc

Toyo is a young, vibrant woman who quits her boring job in Watanabe's office to find more fulfilling work. She does not have a dramatic arc herself but serves as the unwitting catalyst for Watanabe's transformation. Her simple, unpretentious joy in life and her work making toys provides Watanabe with the crucial insight he needs to find his own path.

The Novelist

Yūnosuke Itō

Motivation

He is motivated by a kind of cynical pity for Watanabe and a desire to show this dying man what he considers to be "life." He proclaims, "It's our human duty to enjoy life. Wasting it is desecrating God's great gift."

Character Arc

The novelist is an eccentric, cynical character who acts as Watanabe's guide through the hedonistic underworld of Tokyo's nightlife. He believes in seizing life through carnal pleasures. While he introduces Watanabe to a new world, he ultimately represents a false path to meaning, which Watanabe rejects. He serves as a contrast to the genuine, simple path Watanabe eventually chooses.

Mitsuo Watanabe

Nobuo Kaneko

Motivation

His main motivation is securing his financial future and inheritance. He views his father's late-life behavior with suspicion and resentment, believing the money is being squandered.

Character Arc

Mitsuo is Watanabe's son, whose arc is largely static. He remains emotionally distant and self-absorbed throughout the film. He misunderstands his father's final actions and is primarily concerned with his inheritance. His character highlights the generational gap and the breakdown of familial duty and connection in post-war Japan.

Symbols & Motifs

The Swing in the Park

The swing symbolizes Watanabe's rebirth, his brief moment of pure joy, and the successful culmination of his life's purpose. It represents a return to a childlike innocence and a peaceful acceptance of his life and impending death. His gentle swaying while singing in the snow is an image of serene fulfillment.

The most iconic scene of the film shows Watanabe sitting on the swing in the park he helped build, in the middle of a snowy night, shortly before his death. He is singing "Gondola no Uta," a song about the brevity of life, but now with contentment instead of despair. The empty, swaying swings at the end of the film can be seen as an invitation for the audience to find their own purpose.

Watanabe's Hat

The hat serves as a symbol of Watanabe's transformation. His old, worn-out hat represents his former, lifeless self. After his diagnosis, he buys a new, more modern hat, symbolizing his attempt at a rebirth and his decision to live differently.

Watanabe's old hat is shown during his anxious moments at the doctor's office. He later loses it during his night of debauchery. The purchase of the new hat marks a turning point, a conscious decision to break from his past and embrace a new, albeit short, life.

The Cesspool / The Park

The stagnant, polluted cesspool represents Watanabe's own life—stale, meaningless, and a source of harm (like the mosquitoes sickening the children). Its transformation into a vibrant children's playground symbolizes his own redemption and the creation of a meaningful, life-affirming legacy out of his formerly wasted existence.

A group of mothers initially petitions Watanabe's office to have the cesspool cleaned up, but their request is lost in bureaucratic shuffling. After his awakening, Watanabe makes it his sole mission to overcome all obstacles and turn this wasteland into a place of joy and life, which he ultimately achieves.

Toyo's Mechanical Rabbits

The simple mechanical rabbits symbolize finding joy and purpose in small, creative acts. Toyo's happiness in making toys that will bring joy to children helps Watanabe realize that meaning can be found in making things for others, inspiring his own project.

When Watanabe presses his young friend Toyo for her secret to being so alive, she tells him about her new job in a factory making toy rabbits. She explains, "Making these, I feel like I'm playing with every baby in Japan." This simple statement is a moment of epiphany for Watanabe.

Memorable Quotes

I can't afford to hate people. I don't have that kind of time.

— Kanji Watanabe

Context:

Watanabe says this in response to someone commenting on the frustrating and hateful people he must deal with in the bureaucracy while pushing his park project forward. It shows his single-minded dedication to his new purpose.

Meaning:

This line encapsulates Watanabe's state of mind after his transformation. Faced with a deadline, he realizes that negative emotions like anger and resentment are a waste of his precious remaining time. His focus is entirely on his goal, making him immune to the petty frustrations of bureaucracy and interpersonal conflicts.

How tragic that man can never realize how beautiful life is until he is face to face with death.

— The Novelist

Context:

The novelist says this to Watanabe in a bar as he begins to guide him through Tokyo's nightlife. He is explaining why Watanabe's misfortune has, in a way, opened his eyes to the truth of existence.

Meaning:

This quote, spoken by the cynical novelist, ironically captures the central theme of the film. It's a statement on the human condition: we often take life for granted, only appreciating its value when we are about to lose it. It perfectly describes the catalyst for Watanabe's own journey.

Life is brief, fall in love, maidens. Before the crimson bloom fades from your lips.

— Kanji Watanabe (singing)

Context:

Watanabe sings this song on two key occasions. First, in a nightclub, where his sad rendition silences the room. The second and more famous instance is in the film's climax, as he sits on the swing in the park he created, just before he dies.

Meaning:

These are the lyrics to the 1915 song "Gondola no Uta." The song's meaning shifts with Watanabe's character arc. When he first sings it in a nightclub, it is a mournful lament for his wasted life. When he sings it at the end, on the swing in the park, it becomes a peaceful, contented acceptance of life's fleeting beauty.

Philosophical Questions

What does it mean 'to live'?

The film's title translates to "To Live," and the entire narrative is an exploration of this question. It contrasts mere existence—Watanabe's 30 years of monotonous work—with a life of purpose. The film suggests that living is not about the passage of time but about conscious, meaningful action. It rejects hedonism as a path to fulfillment and instead posits that a true life is found in creation, altruism, and connecting with others, even if it's only for a short time.

Can one person make a difference against an inert system?

"Ikiru" explores the struggle of the individual against a faceless, inefficient bureaucracy. Watanabe, a single man with no power and limited time, manages to push through a project that multiple departments had ignored for years. His success affirms the power of individual will and perseverance. However, the ending, where his colleagues revert to their old ways, complicates this, suggesting that while one person can achieve a specific goal, changing the system itself is a far more difficult, perhaps impossible, task.

Is the awareness of death necessary to live authentically?

The film strongly argues that it is. Watanabe is spiritually dead for decades and is only 'reborn' when he learns of his impending death. This existential shock is the sole catalyst for his transformation. The film poses the question to the audience: must we wait for a terminal diagnosis to examine our own lives? It serves as a powerful piece of Memento mori, urging viewers to find purpose before it's too late.

Alternative Interpretations

While the dominant interpretation of "Ikiru" is one of hopeful redemption, some critics offer a more cynical reading of the ending. This perspective focuses on Watanabe's colleagues at his wake. After spending the night piecing together his story and tearfully vowing to live with the same purpose and integrity, they return to work the very next day and immediately fall back into their old, mindless bureaucratic routines.

This interpretation suggests that Watanabe's transformation was a singular, isolated event that ultimately failed to inspire lasting change in the system he fought against. His heroic act, therefore, might be seen not as a triumph that redeems society, but as a beautiful, tragic exception that proves the rule of systemic inertia. The final shot of another bureaucrat walking past the park, barely giving it a glance, could support this view—that Watanabe's legacy is cherished by the community but ignored by the very people who should have learned from it. The film, from this angle, is less a story of universal hope and more a somber reflection on the immense difficulty of effecting genuine change.

Cultural Impact

"Ikiru" is widely regarded as one of Akira Kurosawa's greatest masterpieces and one of the finest films ever made. Released in post-war Japan, it resonated deeply with a society grappling with rapid modernization and the loss of traditional values, offering a powerful critique of the dehumanizing nature of bureaucracy.

Its influence on cinema is profound and far-reaching. The film's existential themes and its narrative structure—particularly the use of flashbacks from a wake to piece together a person's final days—have been influential. Its story of finding meaning in the face of death has inspired countless films that explore similar existential questions. Roger Ebert considered it Kurosawa's greatest film and one of the few movies that could genuinely inspire a person to live their life differently.

The film received immediate critical acclaim in Japan and, though its international release was delayed, it eventually garnered universal praise for its humanism, powerful performances, and masterful direction. It remains a cornerstone of humanist cinema, studied in film schools and cherished by audiences worldwide for its timeless and universal message about what it truly means to live.

Audience Reception

Audiences have consistently lauded "Ikiru" as a deeply moving and profound cinematic experience. The performance of Takashi Shimura as Kanji Watanabe is universally praised as one of the greatest in film history, with viewers finding his transformation from a listless bureaucrat to a man with a mission incredibly powerful and sympathetic. The film's emotional weight, particularly the iconic scene on the swing, resonates strongly with viewers, often cited as one of the most poignant moments in cinema.

The main point of praise is the film's universal and timeless theme: the search for meaning in life. Many viewers express that the film prompted them to reflect on their own lives and priorities. Some minor criticisms point to the film's deliberate pacing, especially in the first half, which some find slow. However, most agree that this pacing is essential to establish the monotony of Watanabe's life, making his eventual transformation all the more impactful. Overall, the audience verdict is that "Ikiru" is a masterpiece of humanist filmmaking—a sad, beautiful, and ultimately life-affirming film.

Interesting Facts

- The screenplay for "Ikiru" was partly inspired by Leo Tolstoy's 1886 novella "The Death of Ivan Ilyich," which also tells the story of a high-ranking official who confronts the emptiness of his life after being diagnosed with a terminal illness.

- Director Akira Kurosawa and his co-writers first conceived of the film's structure with the protagonist's death occurring halfway through, a suggestion from writer Hideo Oguni. This narrative choice allows the second half to explore the meaning of his life through the recollections of others.

- The song Watanabe sings, "Gondola no Uta," was a real Japanese folk-pop song from 1915. None of the screenwriters knew the lyrics beyond the first line, so they had to consult an elderly receptionist on the film set to get the full words and title.

- Takashi Shimura, who gave a career-defining performance as the elderly Kanji Watanabe, was only 47 years old during filming.

- "Ikiru" was made between two of Kurosawa's most internationally famous films: "Rashomon" (1950) and "Seven Samurai" (1954).

- The film was remade in 2022 as the British film "Living," starring Bill Nighy, who received an Academy Award nomination for his performance.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!