晩春

Late Spring - Symbolism & Philosophy

Symbols & Motifs

The Vase

The vase is a powerful and multi-layered symbol. On one level, it represents traditional Japanese aesthetics and femininity. More profoundly, it symbolizes the stasis and unspoken emotions of Noriko. In a famous sequence, a shot of the vase separates a shot of Noriko smiling from one of her on the verge of tears, suggesting a profound internal emotional shift that remains unarticulated. It is an empty object waiting to be filled, reflecting Noriko's transition from one stage of life to another.

The most discussed appearance is during the trip to Kyoto. After Noriko expresses a change of heart about marriage, her father falls asleep. Ozu cuts to a lengthy, static shot of a vase in the dark room before cutting back to Noriko, whose expression has changed from a smile to one of sadness. This "pillow shot" suspends the narrative to evoke a deep, internal emotional state.

Peeling the Apple

In the final scene, the act of Shukichi peeling an apple symbolizes his profound loneliness and vulnerability. As he finishes, the long, continuous peel breaks, mirroring the breaking of his family unit and his composure. The peeled apple is stripped bare, much like he is now stripped of his daughter's companionship, left exposed to his grief.

This occurs in the film's final moments. After Noriko's wedding, Shukichi returns to his empty home. He sits alone and begins to peel an apple. When the peel breaks, he bows his head in sorrow, a quiet, devastating final image of his sacrifice.

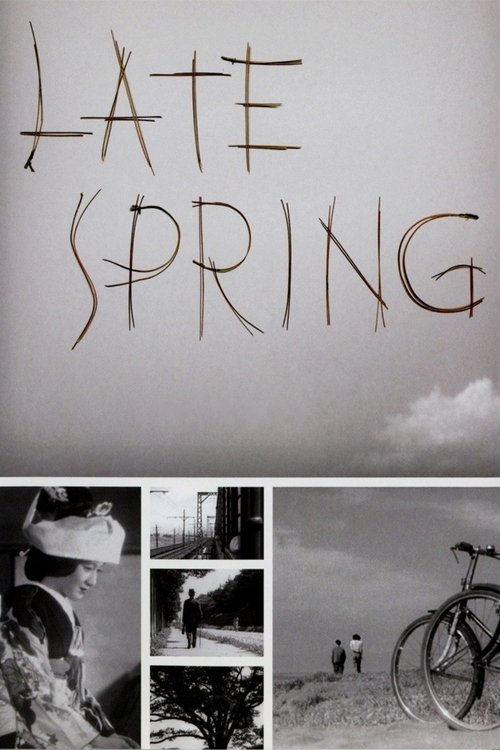

Trains and Bicycles

Trains and bicycles represent journeys, transitions, and the passage of time. The opening shots of train tracks establish this theme of movement and change. The bicycle ride Noriko shares with her father's assistant, Hattori, symbolizes a fleeting moment of youthful freedom and a potential, unpursued path in her life, set against the backdrop of a modernizing, American-influenced Japan (indicated by a Coca-Cola sign).

The film begins with shots of a train station. Later, Noriko and Hattori go for a bicycle ride along the coast, a scene noted for its rare camera movement in an Ozu film and its prominent placement of a Coca-Cola advertisement.

Noh Theatre

The Noh performance represents tradition, unspoken emotion, and a pivotal moment of realization for Noriko. The highly stylized and formal nature of Noh mirrors the emotional restraint of the characters. It is during the performance that Noriko witnesses her father acknowledging Mrs. Miwa, which solidifies her belief that he intends to remarry, thus sealing her own fate.

Shukichi and Noriko attend a Noh play. During the performance, Shukichi smiles and nods at Mrs. Miwa. Noriko observes this interaction, and her subtle change in expression reveals her inner turmoil and resignation to the coming changes in her life.

Philosophical Questions

Is personal happiness subservient to familial duty and societal expectation?

The film's central conflict forces both Noriko and her father to choose between their personal desire to stay together and their perceived duty to follow life's traditional path. They both sacrifice their happiness for this ideal, but the film's sorrowful conclusion leaves the audience questioning the virtue and outcome of this sacrifice. It suggests that fulfilling one's duty does not guarantee happiness and may, in fact, lead to profound loneliness and regret.

What is the nature of happiness?

Shukichi tells Noriko that happiness isn't something one simply finds or waits for; it must be actively created through effort. The film explores this by contrasting Noriko's passive contentment in her life with her father against the uncertain, effortful happiness she must now try to build in a marriage. It challenges the romantic notion of marriage as an automatic source of joy, presenting it instead as a difficult, long-term project.

How do we reconcile tradition with the inevitability of change?

"Late Spring" is set in a Japan caught between ancient traditions and modern influences. The narrative itself—an arranged marriage forcing a family to change—is a microcosm of this larger cultural shift. The film doesn't offer an easy answer but portrays the transition with a deep sense of melancholy, suggesting that while change is an inescapable part of life, it is always accompanied by a sense of loss for what came before.

Core Meaning

The central message of "Late Spring" revolves around the painful yet perceived necessity of sacrifice for the sake of family and adherence to life's cyclical nature. Director Yasujirō Ozu explores the quiet tragedy inherent in societal expectations, particularly the institution of marriage, which forces a loving father and daughter apart. The film suggests that happiness is not a passive state but something that must be actively created, even if it arises from profound personal loss. It is a deeply melancholic meditation on the dissolution of a family unit and the lonely acceptance of life's inevitable changes, questioning whether the fulfillment of duty truly leads to happiness or simply a beautifully rendered sorrow.