Portrait de la jeune fille en feu

"Don't regret. Remember."

Portrait of a Lady on Fire - Symbolism & Philosophy

Symbols & Motifs

The Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice

The myth symbolizes the film's central conflict between love and memory, looking and losing. Orpheus's choice to look back at Eurydice, thereby losing her forever, is debated by the characters. Marianne suggests he makes the 'poet's choice'—to preserve her image in his memory—rather than the 'lover's choice'. This reframes a tragic mistake as a deliberate artistic act. The film further subverts the myth by suggesting Eurydice might have told Orpheus to turn, giving her agency in her own fate.

The myth is read aloud by the three women and becomes a framework for understanding Marianne and Héloïse's doomed romance. Marianne sees herself as Orpheus, choosing to keep the memory of Héloïse. Héloïse's final appearance to Marianne in her wedding dress is a direct visual echo of Eurydice being sent back to the underworld. The lovers know their time is limited, and they must ultimately choose the memory of their love over a future that cannot be.

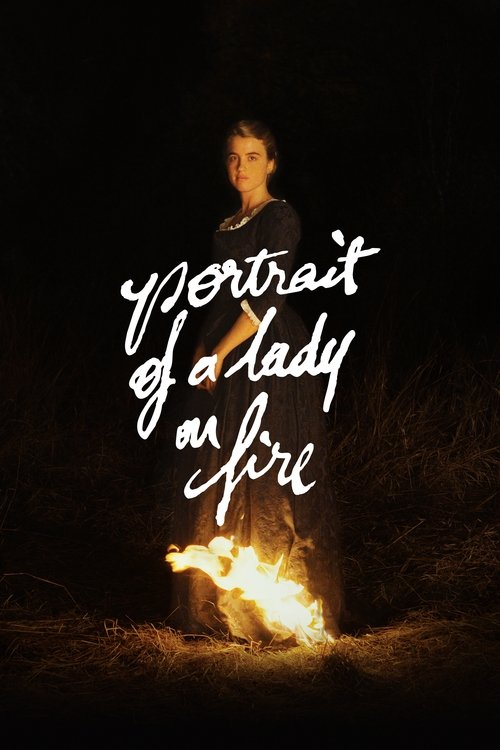

Fire

Fire represents passion, desire, and the intense, fleeting nature of Marianne and Héloïse's love. It is both creative and destructive, a source of warmth and a symbol of a love that burns brightly but cannot last. The titular 'lady on fire' moment solidifies this connection.

The symbol appears repeatedly. The first failed portrait is burned, its destruction making way for a truer depiction born of love. A bonfire scene is where the women's collective bond is celebrated and where Héloïse's dress briefly catches fire, a pivotal moment of exchanged glances that Marianne later captures in a painting. The hearth provides a constant source of light and warmth in the otherwise stark interiors, the setting for many of their most intimate moments.

The Portrait

The portrait is the central object that both unites and separates the lovers. Initially, it represents patriarchal control—an object to be sent to a suitor, sealing Héloïse's fate. However, as Marianne and Héloïse collaborate on the second, true portrait, it transforms into a symbol of their shared gaze, their intimacy, and a testament to a love story told on their own terms. It becomes an act of rebellion and preservation.

The entire plot revolves around the creation of Héloïse's portrait. The first, painted from stolen glances, is rejected by Héloïse as lifeless because it lacks 'presence'. The second, painted with her willing participation, captures her true essence and becomes a monument to their relationship. Years later, it is Marianne's painting, titled 'Portrait of a Lady on Fire,' that triggers her memories, framing the entire film.

Page 28

Page 28 is a secret, intimate symbol of their enduring connection and a testament to how they remember each other across time and distance. It represents a memory that is theirs alone, a hidden message affirming that their love has not been forgotten.

On one of their last nights together, as a keepsake for Héloïse who will have no image of her, Marianne draws a small, nude self-portrait on page 28 of Héloïse's book of Ovid's Metamorphoses. Years later, Marianne sees a portrait of Héloïse with her daughter. In the painting, Héloïse is holding a book, with her finger subtly marking page 28, a deliberate signal to Marianne that she remembers.

Philosophical Questions

Is a love that is remembered more perfect than one that is lived?

The film deeply explores this question through the Orpheus and Eurydice metaphor and its ending. By choosing memory over a continued (and impossible) life together, Marianne and Héloïse preserve their love at its most intense and ideal moment. The film seems to suggest that memory, aided by art, can purify a relationship of the compromises and pains of reality, allowing it to exist eternally in its most powerful form. It questions the conventional definition of a 'happy ending,' proposing that the value of love lies in its impact, not its longevity.

What does it mean to truly 'see' another person?

The film uses the act of portrait painting to examine the nature of perception. The first portrait fails because Marianne has only observed Héloïse's external features, following 'rules and conventions'. The second portrait succeeds because it is born from a relationship of mutual looking and understanding—a shared gaze. The film argues that truly seeing someone involves more than just physical observation; it requires empathy, intimacy, and a willingness to be seen in return. It is a process of collaboration and connection.

Can art be a form of liberation?

For the women in the film, art is both a tool of oppression (the wedding portrait) and a means of liberation. In the act of painting and being painted, Marianne and Héloïse find a private language and a space of freedom where they can define themselves and their relationship outside of societal expectations. Marianne's ability to live as an artist gives her a degree of independence unavailable to Héloïse. Furthermore, the act of painting Sophie's abortion is a radical act of claiming their own stories and making the invisible visible, transforming a hidden reality into a subject worthy of art.

Core Meaning

At its heart, Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a profound meditation on the female gaze, memory, and the power of art to immortalize a love that society forbids. Director Céline Sciamma crafts a narrative that intentionally subverts the traditional male gaze prevalent in art and cinema, instead presenting a love story built on equality, reciprocity, and mutual observation. The film explores how love and art are intertwined, with the act of creating the portrait becoming an intimate exchange that allows both women to truly see and be seen. It posits that a love story's value is not measured by its duration but by its transformative impact. The film argues that memory can be an act of preservation, a way to hold onto the essence of a person and a feeling long after they are gone, suggesting that some connections are so profound they continue to exist and shape us, even in absence.