Au revoir là-haut

See You Up There - Symbolism & Philosophy

Symbols & Motifs

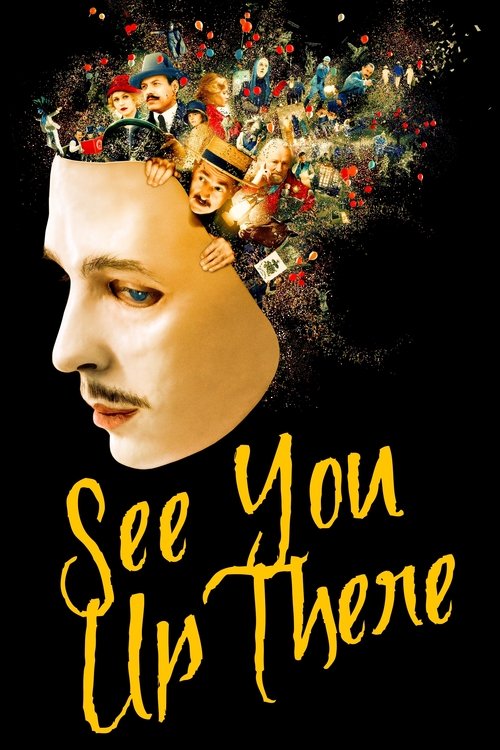

The Masks

The masks are the film's most powerful symbol. They represent Édouard's lost voice and face, but also his defiant artistic spirit. Each mask is a new identity, a mood, and a form of communication, transforming a horrific injury into a source of stunning, surreal beauty. They symbolize the facade society itself puts on after the war—a beautiful, roaring twenties exterior hiding the ugly trauma underneath. They are both a prison and a liberation for Édouard.

Édouard creates and wears dozens of unique masks throughout the film to hide his disfigured jaw. They range from simple and melancholic to extravagantly theatrical, often reflecting his emotional state or the specific needs of their scam. They become his primary way of interacting with the world, with the young girl Louise often acting as his interpreter.

War Memorials

The war memorials (or the lack thereof) symbolize the hollow and commercialized nature of national grief. The scam itself is a cynical commentary on how society prefers to invest in stone effigies rather than care for the living soldiers. It highlights the absurdity of patriotic remembrance when the ideals fought for have been corrupted.

The central plot revolves around Albert and Édouard's fraudulent business of selling designs for war memorials to municipalities across France. They create an elaborate catalog of heroic, jingoistic, and sometimes absurd designs, none of which they ever intend to build.

Being Buried Alive

This recurring motif symbolizes the suffocating trauma of war and the feeling of being trapped by one's circumstances. It represents both a literal death in the trenches and the metaphorical death of the soldiers' former selves. Albert's survival from this ordeal ties him irrevocably to Édouard and the horrors they endured.

The film's pivotal trench scene shows Albert being pushed into a shell crater by Pradelle and slowly being buried alive, only to be rescued by Édouard at the last second. The imagery of suffocation and confinement reappears in their cramped, impoverished post-war life, contrasting with the open opulence of the Péricourt and Pradelle households.

Philosophical Questions

What is the true meaning of remembrance and honor?

The film critically examines society's methods of honoring its war dead. It juxtaposes the official, state-sanctioned creation of monuments and cemeteries with the neglect of the living, traumatized soldiers. The central scam mocks the very idea of memorialization, suggesting that these stone tributes are more about assuaging collective guilt and political posturing than genuine honor. The film asks whether true honor lies in grand monuments or in the quiet loyalty and care shown between individuals like Albert and Édouard.

Can art be a valid response to profound trauma?

Édouard's entire post-war existence is an exploration of this question. His disfigurement is a direct result of violence, and his response is not to hide in shame but to create. His masks are a defiant act of turning horror into beauty. The film suggests that art is not merely decorative but can be a vital tool for survival, communication, and rebellion. It allows Édouard to process his trauma, reclaim his identity, and even exact revenge, proposing that creativity can be the most potent weapon against despair.

Where is the line between crime and justice in a corrupt society?

The film presents two parallel crimes: the artistic fraud of Albert and Édouard and the ghoulish war-profiteering of Pradelle. While our protagonists are technically criminals, the film frames their actions as a form of poetic justice. They scam a society that has abandoned them, while Pradelle, a decorated officer, commits far more heinous acts under the guise of patriotism and business. The film forces the audience to question conventional morality, suggesting that in a system where the powerful are the biggest criminals, an illegal act of rebellion can be the most just course of action.

Core Meaning

"See You Up There" is a powerful indictment of the absurdity and brutality of war, and more pointedly, its cynical aftermath. Director Albert Dupontel uses the story of two traumatized veterans to explore how a nation's patriotic fervor quickly gives way to neglect, leaving those who sacrificed the most to fend for themselves. The film posits that in a corrupt world that profits from death and glorifies memory while scorning the living survivors, the ultimate act of rebellion and survival is a theatrical, audacious swindle. It is a darkly humorous, picaresque tale about the "lost generation," contrasting the vibrant, frantic energy of the Jazz Age with the lingering scars of the trenches. Through Édouard's art—his magnificent, expressive masks—the film champions the power of creativity to reclaim identity, communicate unspeakable pain, and create beauty out of horror. Ultimately, it's a story of poetic justice, suggesting that true honor is found not in monuments, but in loyalty and defiance against a hypocritical society.