"A murder case of Madam D. with enormous wealth and the most outrageous events surrounding her sudden death!"

The Grand Budapest Hotel - Symbolism & Philosophy

Symbols & Motifs

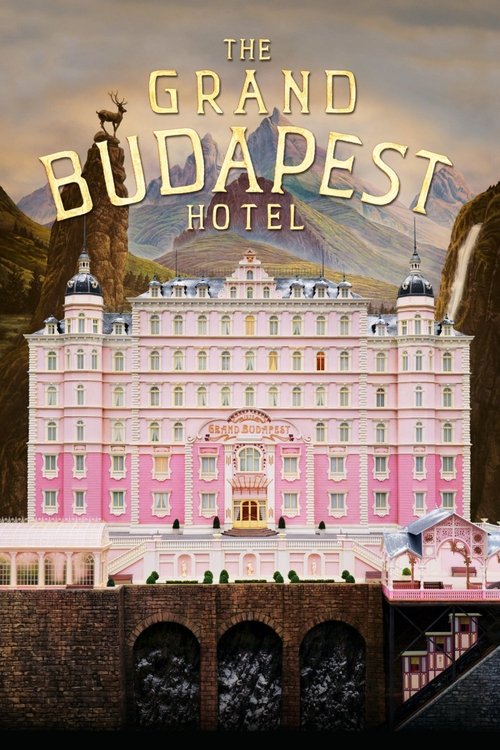

The Grand Budapest Hotel

The hotel itself symbolizes a lost, pre-war Europe—a bastion of culture, refinement, and civility. Its physical state directly reflects the era: vibrant and grand in the 1930s, stark and impersonal in the communist-era 1960s. Its decline mirrors the decay of the civilized values Gustave champions.

The hotel is the central setting for the main story in 1932. Later, in 1968, the Author meets the owner, Mr. Moustafa, in its faded, nearly empty dining hall. The changing architecture and color palette of the hotel signify the passage of time and the erosion of its former glory.

Boy with Apple Painting

This priceless Renaissance painting is the film's MacGuffin, driving the plot. It symbolizes immense wealth and the greed it inspires in the Desgoffe-und-Taxis family. For Gustave, it represents Madame D.'s affection and a link to the world of aristocratic luxury he aspires to. Ultimately, it becomes the key to his exoneration and inheritance. The painting itself, a fictional creation for the film, represents a piece of timeless art caught in the crossfire of modern brutality.

Bequeathed to Gustave in Madame D.'s will, the painting is stolen by Gustave and Zero, hidden, and pursued by Dmitri and Jopling throughout the film. The crucial second will is eventually found taped to its back.

Mendl's Courtesan au Chocolat

These delicate, beautiful pastries from Mendl's bakery represent a small, perfect piece of the civilized world Gustave is trying to preserve. They are creations of artistry and refinement, a stark contrast to the ugliness of prison and fascism. They are also a symbol of love and connection, as they are made by Zero's beloved, Agatha.

The pastries are used throughout the film. Zero first meets Agatha when picking them up. Later, Agatha hides tools for a prison break inside them. Their perfect, delicate structure is often juxtaposed with moments of danger and chaos.

L'Air de Panache

M. Gustave's signature perfume symbolizes his unwavering commitment to his own refined persona, even in the most dire circumstances. It's an armor of civility. His near-obsession with it, even after breaking out of prison, highlights his belief that maintaining one's standards is a form of resistance against the chaos of the world.

Gustave is almost never without his perfume. He is horrified when Zero forgets to pack it for their escape from prison. Later, in a moment of bonding, he gives the perfume to Zero after being resupplied by a member of the Society of the Crossed Keys.

Philosophical Questions

Can civility and grace survive in a world descending into barbarism?

The film explores this through the character of M. Gustave, who clings to etiquette, poetry, and kindness as fascism rises. His efforts are portrayed as both noble and tragically futile. The Society of the Crossed Keys represents a network of decency, but their power is limited. Gustave's ultimate death at the hands of soldiers suggests that, in the end, brute force overwhelms civility. The film leaves the audience to ponder whether the *memory* of such grace is the only form in which it can truly survive.

How does nostalgia shape our understanding of the past?

"The Grand Budapest Hotel" presents the past through the lens of memory, colored by love and loss. The vibrant, almost dreamlike quality of the 1930s segment contrasts with the bleakness of later years, questioning whether the past was truly as magical as it is remembered. The film suggests that nostalgia is not just a recollection of events, but an act of emotional curation. Zero preserves the hotel not as it is, but as a shrine to what it once was—a vessel for his cherished, and perhaps idealized, memories of Agatha and Gustave.

What is the role of storytelling in preserving history and personal legacy?

The film's frame-story structure highlights the idea that stories are all that remain when people and places are gone. Zero tells his story to the Author to ensure Gustave is not forgotten. The Author, in turn, publishes it, giving these private memories a form of immortality. The film suggests that personal legacies and even the spirit of an entire era are not preserved in monuments, but in the narratives passed from one person to another.

Core Meaning

The core meaning of "The Grand Budapest Hotel" is a lament for a lost past—a world of elegance, civility, and principle that has been irrevocably destroyed by the barbarism of war and fascism. Inspired by the writings of Austrian author Stefan Zweig, the film explores themes of nostalgia, not as a simple longing for "the good old days," but as a complex and often tragic act of memory. M. Gustave represents this bygone era, a man who, as the elder Zero notes, "sustained the illusion of his world with marvelous grace" long after it had already vanished. The film suggests that storytelling and memory are the only ways to preserve these ideals, even if the recollection is tinged with sadness and loss, creating a fragile bulwark against the darkness of history.