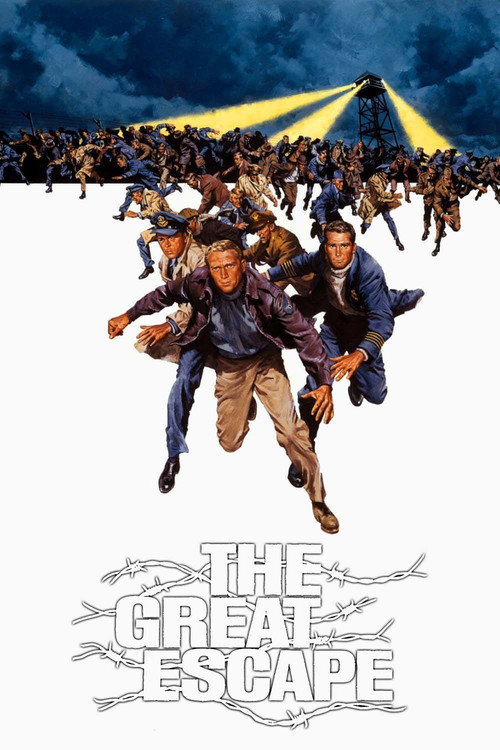

"Put a fence in front of these men... and they'll climb it!"

The Great Escape - Ending Explained

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

The entire, meticulously planned escape hinges on the success of the tunnel "Harry." On the night of the escape, 76 prisoners manage to get out before the tunnel is discovered. However, the tunnel exit is discovered to be short of the woods, making the initial escape from the camp perilous. The film then splinters, following the desperate journeys of several key groups of escapees.

The ultimate outcome is tragic and underscores the brutality of the Nazi regime. Of the 76 men, only three make it to freedom: Danny and Willy (the Tunnel Kings) escape by boat, and Sedgwick (the Manufacturer) escapes to Spain with the help of the French Resistance. Most are recaptured. In a horrifying act of reprisal ordered by Hitler, the Gestapo executes 50 of the recaptured officers, including the mastermind Roger Bartlett, his second-in-command MacDonald, and Ashley-Pitt, who is killed at a train station checkpoint. Hendley and his blind friend Colin Blythe steal a plane, but they crash short of the Swiss border, and Blythe is shot and killed by German soldiers. Hilts' famous motorcycle chase ends with him being captured after crashing into barbed wire at the Swiss border.

The film concludes with Hilts and the other survivors being returned to Stalag Luft III. Hilts is thrown back into the cooler, but the sound of his baseball bouncing against the wall signifies his unbroken spirit and the enduring legacy of their defiance. The grim reality that their great escape led to the murder of 50 men provides a sobering and powerful final message about the true cost of freedom and duty during the war.

Alternative Interpretations

While on the surface "The Great Escape" is a straightforward war adventure, some critics have offered alternative readings. One interpretation views the film less as a historical document and more as a celebration of a particular brand of masculinity, emphasizing camaraderie, stoicism, and rebellious individualism, embodied by stars like McQueen and Bronson. The almost complete absence of women focuses the narrative squarely on the dynamics of male bonding and heroism in a high-stakes environment.

Another perspective, noted by critics like Bosley Crowther in 1963, is that the film presents a romanticized and 'Rover Boyish' version of POW life, glossing over the true horrors of war. The tone is often light and adventurous, which could be interpreted as trivializing the grim reality of the prisoners' situation. This interpretation suggests the film functions more as an escapist fantasy than a gritty war drama, choosing entertainment value over a stark depiction of the inhumanity of the conflict.