Das Leben der Anderen

"Before the Fall of the Berlin Wall, East Germany's Secret Police Listened to Your Secrets."

The Lives of Others - Ending Explained

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

The central twist of "The Lives of Others" is not a sudden event, but the gradual, profound transformation of its protagonist, Stasi agent Gerd Wiesler. The true reveal is that the relentless hunter becomes the silent guardian. Initially tasked with finding incriminating evidence on Georg Dreyman, Wiesler, moved by the couple's love and art, begins to actively protect them. He omits crucial details from his reports, such as when he conceals Dreyman's plan to write a dissident article about East Germany's suppressed suicide statistics.

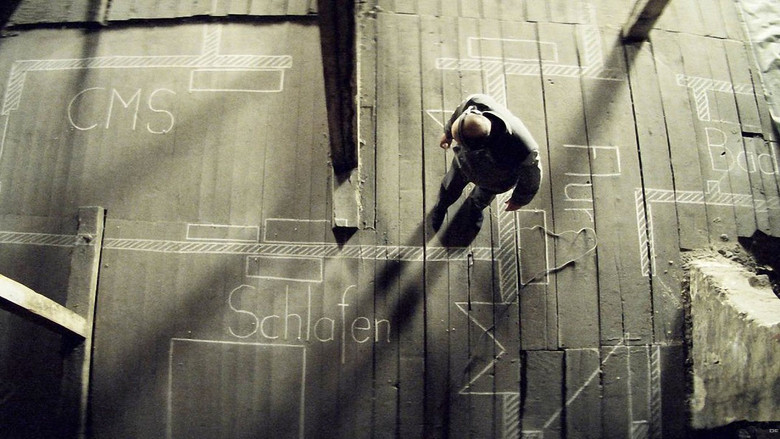

The climax of this deception occurs after Christa-Maria Sieland, broken under interrogation by Wiesler himself, reveals the hiding place of the contraband typewriter used to write the article. In a heart-pounding sequence, Wiesler arrives at the apartment moments before his colleagues and removes the typewriter, hiding it himself. When the Stasi search team, led by a suspicious Grubitz, tears up the floorboard, they find nothing. This act of sabotage saves Dreyman but effectively ends Wiesler's career; Grubitz, knowing something is amiss, demotes him to the mind-numbing purgatory of steaming letters in a basement department for the rest of his days with the Stasi.

A devastating turn is Christa-Maria's fate. Overwhelmed by guilt for her betrayal and seeing the look on Dreyman's face as he realizes she was the informant, she runs out into the street and is fatally struck by a truck. Her tragic end underscores the immense human cost of the regime's psychological cruelty.

The film's ending provides a quiet, deeply satisfying resolution. Years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Dreyman learns from the former Minister of Culture that he was, in fact, under constant surveillance. Puzzled, he accesses his own Stasi file. He discovers the reports are incomplete and falsified, and a red ink fingerprint on the final report leads him to the stunning realization that the agent in charge, HGW XX/7, was his savior. Dreyman tracks down Wiesler, who is now a humble mailman, but chooses not to confront him, understanding that the greatest acknowledgment would be through his art. Two years later, Wiesler sees Dreyman's new novel, "Sonata for a Good Man," in a bookstore window. He opens it to find the dedication: "To HGW XX/7, with gratitude." When the clerk asks if he'd like the book gift-wrapped, Wiesler's final line, "No. It's for me," confirms that he has finally claimed his own story of redemption.

Alternative Interpretations

While the dominant interpretation of "The Lives of Others" is that of a hopeful story of redemption and the triumph of the human spirit, several alternative and critical readings exist.

A Historically Inaccurate Fantasy: Some critics and historians, notably Hubertus Knabe, director of the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Memorial, have argued that the film is a dangerous falsification of history. The central premise of a Stasi officer like Wiesler having a crisis of conscience and actively protecting his targets is seen as pure fiction. From this perspective, the film is not a realistic portrayal but a form of "liberal wish-fulfilment," creating a comforting narrative of a 'good German' within the oppressive system that never actually existed. This interpretation suggests the film softens the horrific, monolithic reality of the Stasi, where such dissent from within was virtually unthinkable and unrecorded.

A Bourgeois Triumphalist Narrative: Another critical view posits that the film elevates the suffering and moral dilemmas of a privileged intellectual and artistic class while marginalizing the experiences of ordinary citizens. Dreyman and Sieland are celebrated cultural figures whose lives are deemed worthy of redemption. The film's focus on "High Art" (poetry, theatre, classical music) as the catalyst for change can be seen as an elitist perspective. This reading argues that the film's 'pretensions towards universal human values' are undermined by a focus on the 'narcissistic vanity of its pampered celebrities'.

Wiesler's Transformation as Selfish: A more cynical psychological reading of Wiesler's arc could argue that his transformation is not purely altruistic. Trapped in a lonely, sterile existence, Wiesler becomes a voyeur who develops an obsessive, vicarious attachment to the vibrant, emotional, and erotic lives of Dreyman and Sieland. From this viewpoint, his actions to protect them are also actions to preserve the source of his only emotional connection and stimulation. He isn't just saving them; he is saving himself from the utter nullity of his own existence, making his motivation more complex and less purely heroic.