The Lives of Others

Das Leben der Anderen

"Before the Fall of the Berlin Wall, East Germany's Secret Police Listened to Your Secrets."

Overview

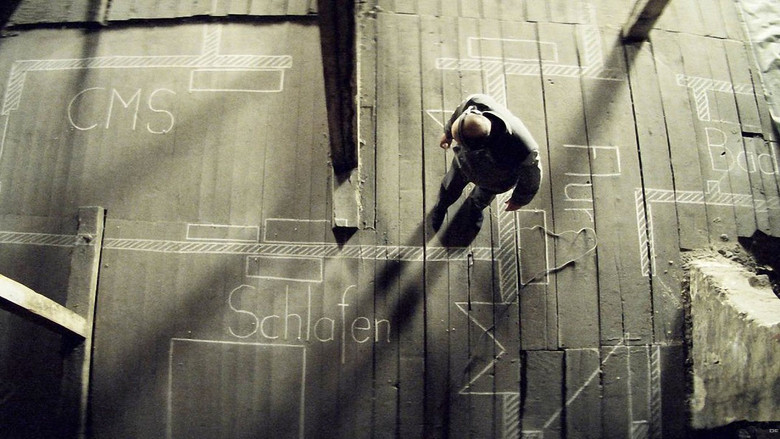

Set in 1984 East Berlin, "The Lives of Others" chronicles the intense surveillance of a celebrated playwright, Georg Dreyman, and his actress-lover, Christa-Maria Sieland. The operation is initiated not out of genuine political suspicion, but due to the corrupt Minister of Culture's desire for Sieland.

The Stasi agent assigned to the case is the cold and dedicated Hauptmann Gerd Wiesler. Initially a fervent believer in the socialist state, Wiesler meticulously monitors the couple's every word and action from a listening post in their building's attic. However, as he becomes an invisible fixture in their lives—witnessing their love, their artistic passions, their fears, and their moral compromises—the surveillance begins to profoundly change him.

Wiesler's ideological certainties start to crumble as he is exposed to a world of art, literature, and free thought that is entirely alien to his own barren existence. He starts to empathize with his targets and subtly intervenes to protect them, a dangerous game that puts his career and life at risk. The film builds into a tense human drama about morality, the power of art, and the capacity for change in the most oppressive of systems.

Core Meaning

The core meaning of "The Lives of Others" is a profound exploration of the transformative power of empathy and art in the face of a dehumanizing totalitarian regime. Director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck crafts a human drama about the ability of individuals to choose morality and do the right thing, no matter how far down the wrong path they have gone. The film posits that exposure to genuine human connection, love, and artistic expression—symbolized by literature and music—can awaken the dormant humanity in even the most hardened ideologue. It serves as a powerful testament to the idea that no system of oppression can completely extinguish the human spirit and the capacity for compassion. Ultimately, it is a story of quiet rebellion and redemption, suggesting that small, unseen acts of courage can have a profound and lasting impact.

Thematic DNA

The Dehumanizing Nature of Surveillance

The film relentlessly portrays the pervasive climate of fear, paranoia, and mistrust fostered by the Stasi's surveillance. This constant monitoring infiltrates the most intimate aspects of life, eroding privacy and personal relationships. The sterile, grey world of Wiesler and the Stasi headquarters visually contrasts with the warmth of Dreyman's apartment, symbolizing the crushing effect of the state on individuality and creativity. The regime's power lies in making citizens informants against each other, turning even loved ones into potential threats, as seen in the pressure exerted on Christa-Maria.

The Transformative Power of Art and Empathy

Art is depicted as a powerful, humanizing force that transcends ideology. Dreyman's Brechtian plays, his reading of poetry, and most notably, the piano piece "Sonata for a Good Man," directly impact Wiesler. Listening to the sonata marks a pivotal moment in his transformation, causing him to weep and question the nature of good and evil. This exposure to the world of ideas and emotions, which his own life lacks, awakens his empathy. He begins to live vicariously through his targets, and this newfound connection compels him to protect them, demonstrating that art can inspire moral awakening and redemption.

Moral Compromise and Integrity

The film examines the difficult choices individuals make under oppressive rule. Christa-Maria Sieland embodies the struggle of moral compromise; she betrays Dreyman under immense pressure from the Stasi, driven by fear and her addiction, which is exploited by Minister Hempf. In contrast, Dreyman evolves from a playwright loyal to the state to a dissident who risks everything to expose the truth about suicide rates in the GDR. Wiesler's journey is the central exploration of integrity; he sacrifices his entire career and identity for a moral principle, evolving from a perpetrator of the system to its quiet saboteur.

The Fallibility of Ideology

Wiesler's character arc is a direct critique of rigid, state-enforced ideology. Initially, he is a true believer, a man who sees his work as protecting the Party. However, the surveillance operation reveals the hypocrisy and corruption of the system's leaders, like Minister Hempf, who uses the state apparatus for personal gain. This realization, combined with his exposure to the artists' humanity, causes his faith in the socialist cause to crumble. The film suggests that ideologies built on control and suppression are ultimately fragile because they cannot account for the complexities of human nature and compassion.

Character Analysis

Gerd Wiesler (HGW XX/7)

Ulrich Mühe

Motivation

Initially, his motivation is ideological purity and professional duty to the state. He believes he is protecting the Party from its enemies. This shifts as he witnesses the corruption of his superiors and, more importantly, is moved by the art and human connection he observes. His motivation becomes a deeply personal, moral, and empathetic need to preserve the goodness he finds in 'the lives of others.'

Character Arc

Wiesler begins as a cold, exemplary Stasi officer, a true believer in the socialist system and an expert in psychological interrogation. His arc is one of profound transformation. As he surveils Dreyman and Sieland, their lives—filled with love, art, and intellectual debate—expose the emptiness of his own. He moves from passive observer to active protector, subtly manipulating events, falsifying reports, and ultimately sacrificing his career to save Dreyman. After the fall of the Wall, he is a forgotten man delivering mail, but his redemption is complete when he sees Dreyman's novel dedicated to him, acknowledging his humanity. His final line, "No, it's for me," signifies his acceptance of his new identity.

Georg Dreyman

Sebastian Koch

Motivation

His primary motivation is his love for art, for Christa-Maria, and a fundamental belief in the goodness of people. This is initially channeled into his plays, but as the regime's brutality hits close to home, his motivation shifts to a need for justice and truth, using his artistic talents as a weapon against the state.

Character Arc

Dreyman starts as a successful playwright who is, to some extent, a model citizen of the GDR, believing he can work within the system. He is initially naive to the full extent of the state's cruelty. His transformation is spurred by the suicide of his blacklisted friend, director Albert Jerska. This tragedy awakens him to his own moral compromises and compels him to take a stand. He evolves from a state-approved artist to a courageous dissident, risking his life to write and publish an article exposing the state's hidden truths. After reunification, he seeks to understand his past and ultimately honors the man who saved him through his art.

Christa-Maria Sieland

Martina Gedeck

Motivation

Her motivation is a complex mix of artistic ambition, love for Dreyman, and overwhelming fear. She wants to continue acting, the core of her identity, but the price set by the regime is her integrity. Her actions are driven by the desperation to survive in a system that ruthlessly exploits her vulnerabilities.

Character Arc

Christa-Maria is a celebrated actress and the object of both Dreyman's love and Minister Hempf's coercive desires. Her arc is a tragic one of entrapment and compromise. She feels the pressure of the state more directly than Dreyman, forced into an affair with Hempf to protect her career and feed a prescription drug addiction. She is torn between her love for Dreyman and the instinct for self-preservation. Ultimately, she is broken by Stasi interrogation and becomes an informant, a betrayal that leads to her guilt-ridden death after she runs in front of a truck. She represents the fragility of the human spirit under immense, systematic pressure.

Anton Grubitz

Ulrich Tukur

Motivation

His sole motivation is career advancement and personal gain. He sees the surveillance of Dreyman as an opportunity to curry favor with Minister Hempf and climb the ranks of the Stasi. He is driven by ambition and a cynical understanding of how power works in the GDR, rather than any political conviction.

Character Arc

Grubitz is Wiesler's superior and former classmate. Unlike Wiesler, who is an ideologue, Grubitz is a cynical careerist. His character does not have a significant arc; he remains a self-serving opportunist throughout. He uses the system to advance his own career, showing little concern for justice or the principles of socialism. He is ambitious and perceptive, eventually suspecting Wiesler's change of heart and ultimately punishing him with a demeaning, career-ending transfer to steam-opening letters.

Symbols & Motifs

Sonata for a Good Man

This piece of music symbolizes the power of art to touch the human soul and inspire goodness. It is the catalyst for Wiesler's emotional awakening. The question Dreyman poses after playing it—"Can anyone who has heard this music, I mean truly heard it, really be a bad person?"—is the central philosophical query of the film. The sonata represents a world of beauty and empathy that stands in direct opposition to the cold, functional cruelty of the Stasi regime. Dreyman's eventual novel, given the same title, becomes a tribute to Wiesler's silent, good deed, immortalizing his act of redemption through art.

After learning of his friend Jerska's suicide, a devastated Georg Dreyman plays the sonata on his piano. Wiesler, listening in from the attic, is overcome with emotion and weeps. The title later becomes the name of the novel Dreyman writes after discovering Wiesler's actions, dedicating it "To HGW XX/7, in gratitude."

The Red Typewriter

The contraband miniature typewriter represents dissent, free speech, and the power of the written word to challenge oppression. In a state where all typewriters are registered to track authors, this unregistered machine is a tangible instrument of rebellion. It is the tool through which Dreyman can anonymously publish the truth about the GDR's hidden suicide statistics, an act of defiance against state-controlled information.

The typewriter is smuggled in from West Germany and hidden under a floorboard in Dreyman's apartment. It is used to write the explosive article for Der Spiegel. Christa-Maria reveals its location under interrogation, but Wiesler secretly removes it before the Stasi can conduct their final search, thus saving Dreyman.

The Red Ink Fingerprint

The red ink stain on the final surveillance report symbolizes Wiesler's humanity and his 'bloody' hands in both his past as a Stasi agent and his present act of saving Dreyman. It is the unintentional confession of his good deed, a human trace left within the cold, bureaucratic machine of the Stasi archives. This small, accidental mark is the clue that allows Dreyman to piece together the truth about his silent protector years later, signifying that human actions, however hidden, can leave an indelible mark.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Dreyman inspects his Stasi file. He is puzzled by the falsified reports until he sees a red fingerprint on the final entry, the same red as his typewriter's ribbon. This leads him to realize that the officer in charge, HGW XX/7, must have handled and hidden the typewriter, thereby saving him.

The Brecht Poem

The book of Bertolt Brecht's poetry that Wiesler steals from Dreyman's apartment symbolizes his burgeoning curiosity and his first active step toward engaging with the world of ideas he is monitoring. It represents a bridge between his sterile existence and the rich intellectual life of his target. Taking the book is an act of personal, quiet rebellion and a thirst for the humanism that his own life lacks.

During a moment when Dreyman and Christa-Maria are out, Wiesler, under the pretense of planting a bug, enters their apartment. He is drawn to their books and impulsively steals a volume of Brecht's poetry. He is later seen reading it alone in his bleak apartment, a stark contrast to his usual state-approved materials.

Memorable Quotes

Nein. Es ist für mich.

— Gerd Wiesler

Context:

Years after German reunification, Wiesler, now a mailman, sees Dreyman's new novel, "Sonata for a Good Man," in a bookstore window. He goes in and picks up a copy. The clerk asks if he wants it gift-wrapped, and he delivers this poignant final line.

Meaning:

English: "No. It's for me." This is the final line of the film. It signifies Wiesler's complete transformation and his quiet acceptance of his new identity. He is no longer just HGW XX/7, an agent of the state, but a 'good man' who has been touched and changed by art and empathy. Buying the book is not an act of investigation but a personal acknowledgment of his own story and redemption.

Kann jemand, der diese Musik gehört hat, ich meine wirklich gehört hat, ein schlechter Mensch sein?

— Georg Dreyman

Context:

Dreyman says this to Christa-Maria after playing the "Sonata for a Good Man" on the piano, shortly after learning that his friend Albert Jerska has committed suicide. Wiesler overhears this line through his surveillance equipment, and it resonates deeply with him, planting a seed of doubt about his work and his own moral standing.

Meaning:

English: "Can someone who has heard this music, I mean truly heard it, really be a bad person?" This quote encapsulates the film's central theme about the transformative power of art. It suggests that art has a moral dimension and that a genuine aesthetic experience is fundamentally incompatible with true evil or inhumanity. It is this idea that plays out in Wiesler's own transformation.

Sie sind ein guter Mensch.

— Christa-Maria Sieland

Context:

Wiesler, wanting to prevent Christa-Maria from meeting Minister Hempf, anonymously approaches her in a bar. He appeals to her talent and sense of self-worth, encouraging her to be true to herself and her art. Touched by his words, she says this to him before deciding to go home to Dreyman instead.

Meaning:

English: "You are a good man." This is a moment of profound dramatic irony. Christa-Maria says this to Wiesler, whom she does not recognize, believing him to be a stranger showing her kindness. For Wiesler, who knows the true nature of his actions (both as a Stasi agent and as her secret protector), this statement is both a validation of his recent change of heart and a painful reminder of the deception involved. It affirms his new path.

Wir sind Schild und Schwert der Partei.

— Anton Grubitz

Context:

Grubitz says this to Wiesler early in the film, reinforcing their duty and importance within the GDR's power structure. It is stated with a sense of pride and purpose, establishing the ideological world from which Wiesler will eventually break free.

Meaning:

English: "We are the shield and sword of the Party." This quote represents the official self-image and doctrine of the Stasi. It is the ideological justification for their repressive actions, framing them as protectors of the socialist state. It highlights the mindset that Wiesler initially embodies before his transformation begins.

Philosophical Questions

Can art make us better people?

The film directly engages with this question through the "Sonata for a Good Man." Dreyman asks, "Can someone who has heard this music... really be a bad person?" Wiesler's transformation seems to affirm this. His exposure to Dreyman's art and lifestyle awakens his dormant empathy and leads him to a profound moral shift. The film was inspired by a quote from Lenin, who avoided Beethoven because it made him feel 'soft' when he needed to be merciless, suggesting a belief in art's power to alter one's moral compass. The film explores whether aesthetic experience is intrinsically linked to ethical behavior, suggesting that beauty can be a powerful antidote to ideology and cruelty.

What is the nature of good and evil in a totalitarian state?

"The Lives of Others" complicates simplistic notions of good and evil. Wiesler begins as an agent of an evil system but becomes a 'good man.' Christa-Maria is a victim who also becomes a betrayer under duress. Dreyman is a good man who is initially complicit through his silence. The film suggests that morality is not static but a series of choices made under specific, often extreme, pressures. It moves beyond judging characters as simply 'good' or 'bad' and instead examines their capacity for change, compromise, and courage, arguing that true morality lies in the potential for redemption and the decision to act with humanity even when the system demands otherwise.

Does privacy have an intrinsic moral value?

The film is a powerful defense of privacy, showing its absence as fundamentally dehumanizing. The constant surveillance creates a world of paranoia and emotional sterility. As Wiesler intrudes upon the private lives of Dreyman and Sieland, he is ironically humanized by what he sees and hears. Their unguarded moments of love, creativity, and despair are what transform him. The film argues that privacy is the space where authentic humanity—with all its flaws and beauties—is nurtured. Its violation by the state is not just a political act but a profound moral and spiritual one.

Alternative Interpretations

While the dominant interpretation of "The Lives of Others" is that of a hopeful story of redemption and the triumph of the human spirit, several alternative and critical readings exist.

A Historically Inaccurate Fantasy: Some critics and historians, notably Hubertus Knabe, director of the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Memorial, have argued that the film is a dangerous falsification of history. The central premise of a Stasi officer like Wiesler having a crisis of conscience and actively protecting his targets is seen as pure fiction. From this perspective, the film is not a realistic portrayal but a form of "liberal wish-fulfilment," creating a comforting narrative of a 'good German' within the oppressive system that never actually existed. This interpretation suggests the film softens the horrific, monolithic reality of the Stasi, where such dissent from within was virtually unthinkable and unrecorded.

A Bourgeois Triumphalist Narrative: Another critical view posits that the film elevates the suffering and moral dilemmas of a privileged intellectual and artistic class while marginalizing the experiences of ordinary citizens. Dreyman and Sieland are celebrated cultural figures whose lives are deemed worthy of redemption. The film's focus on "High Art" (poetry, theatre, classical music) as the catalyst for change can be seen as an elitist perspective. This reading argues that the film's 'pretensions towards universal human values' are undermined by a focus on the 'narcissistic vanity of its pampered celebrities'.

Wiesler's Transformation as Selfish: A more cynical psychological reading of Wiesler's arc could argue that his transformation is not purely altruistic. Trapped in a lonely, sterile existence, Wiesler becomes a voyeur who develops an obsessive, vicarious attachment to the vibrant, emotional, and erotic lives of Dreyman and Sieland. From this viewpoint, his actions to protect them are also actions to preserve the source of his only emotional connection and stimulation. He isn't just saving them; he is saving himself from the utter nullity of his own existence, making his motivation more complex and less purely heroic.

Cultural Impact

"The Lives of Others" was released 17 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall and was one of the first major German dramas to seriously confront the legacy of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and its secret police, the Stasi. It marked a significant shift from the more comedic treatments of the era, such as "Good Bye, Lenin!", a genre known as "Ostalgie" (nostalgia for the East). The film was met with widespread critical acclaim both in Germany and internationally, culminating in its win for Best Foreign Language Film at the 79th Academy Awards.

Its impact was profound, sparking renewed public dialogue about the nature of the Stasi state and the moral culpabilities of those who lived within it. The film's depiction of the Stasi's methods, while dramatized, was praised for its atmospheric accuracy and its chilling portrayal of a society built on suspicion. It brought the reality of the Stasi's psychological warfare to a global audience. For many viewers, the film was an education on a dark chapter of Cold War history. However, it also faced criticism from some historians and victims of the regime for being historically inaccurate, particularly in its central premise of a Stasi officer's redemption, which some claimed was a case of liberal wish-fulfillment with no real-life precedent.

The film resonated powerfully with modern anxieties about government surveillance and the erosion of privacy in the digital age, making its themes universally relevant. Its tense, character-driven narrative and its exploration of art's role in society have influenced numerous subsequent thrillers and dramas. Ultimately, "The Lives of Others" stands as a landmark of 21st-century German cinema, a powerful and poignant examination of a difficult past that continues to provoke thought and debate.

Audience Reception

"The Lives of Others" received overwhelmingly positive reviews from audiences worldwide, who praised it as a powerful, intelligent, and deeply moving film. Viewers frequently highlighted the masterful and restrained performance of Ulrich Mühe as Gerd Wiesler, noting his ability to convey a profound internal transformation with minimal dialogue. The screenplay was lauded for its tight, suspenseful plotting, where every detail feels significant and contributes to an emotionally resonant conclusion. Many viewers found the story to be an inspiring, albeit heartbreaking, testament to the human spirit, celebrating the capacity for empathy and redemption even in the darkest of times.

The main points of criticism, though less common, often centered on the film's perceived historical implausibility. Some viewers, particularly those with direct experience of the GDR, echoed the critique that the idea of a Stasi officer like Wiesler was unrealistic and overly optimistic. A minority of critics and audience members found the film's approach to be a form of 'bourgeois triumphalism' or 'liberal wish-fulfilment' that created a feel-good narrative at the expense of historical truth. Despite these criticisms, the overall verdict from audiences was that the film is a must-see masterpiece, a tense and thought-provoking drama that lingers long after viewing.

Interesting Facts

- The director, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, got the initial idea for the film after listening to music and recalling a quote from Maxim Gorky about Lenin, who said he couldn't listen to Beethoven's "Appassionata" because it made him want to be gentle when he needed to be ruthless for the revolution. This sparked the image of a secret police agent being moved by the music of his target.

- Ulrich Mühe, who gives a critically acclaimed performance as Gerd Wiesler, had a deeply personal connection to the story. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, he discovered his own extensive Stasi file and learned that he had been spied on by several people, including fellow actors. There were public accusations that his own wife at the time, Jenny Gröllmann, had been an informant, though this was a complex and disputed matter.

- The film was shot over 37 days in the grey Berlin winter. Cinematographer Hagen Bogdanski used a muted, Brechtian color palette of greys and dour greens to evoke the oppressive and drab atmosphere of 1980s East Berlin, wanting to create a world where warmth came only from the people themselves.

- Despite its eventual success, including winning the 2007 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, the film initially struggled to find a distributor. Many German distributors passed on it, feeling it was too dark and intellectual. One broadcaster even suggested it should be remade as a comedy.

- The director of the Hohenschönhausen Memorial (a former Stasi prison) refused permission to film on site, objecting to the idea of "making a Stasi man into a hero." He argued that while there was a real-life Oskar Schindler, there was no real-life compassionate Stasi officer like Wiesler.

- The actors, including established stars Ulrich Mühe and Sebastian Koch, worked for about 10% of their usual fees because they believed so strongly in the script and the importance of the project.

- The typewriter used in the film as a key prop was an authentic Stasi typewriter from the period, adding to the film's meticulous attention to historical detail.

- The film is set in 1984, a deliberate and clear homage to George Orwell's dystopian novel "Nineteen Eighty-Four," which famously depicts a totalitarian surveillance state.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!