Das Leben der Anderen

"Before the Fall of the Berlin Wall, East Germany's Secret Police Listened to Your Secrets."

The Lives of Others - Symbolism & Philosophy

Symbols & Motifs

Sonata for a Good Man

This piece of music symbolizes the power of art to touch the human soul and inspire goodness. It is the catalyst for Wiesler's emotional awakening. The question Dreyman poses after playing it—"Can anyone who has heard this music, I mean truly heard it, really be a bad person?"—is the central philosophical query of the film. The sonata represents a world of beauty and empathy that stands in direct opposition to the cold, functional cruelty of the Stasi regime. Dreyman's eventual novel, given the same title, becomes a tribute to Wiesler's silent, good deed, immortalizing his act of redemption through art.

After learning of his friend Jerska's suicide, a devastated Georg Dreyman plays the sonata on his piano. Wiesler, listening in from the attic, is overcome with emotion and weeps. The title later becomes the name of the novel Dreyman writes after discovering Wiesler's actions, dedicating it "To HGW XX/7, in gratitude."

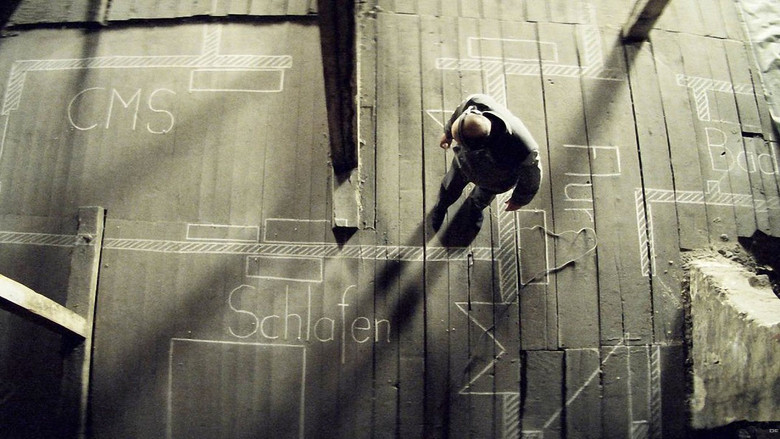

The Red Typewriter

The contraband miniature typewriter represents dissent, free speech, and the power of the written word to challenge oppression. In a state where all typewriters are registered to track authors, this unregistered machine is a tangible instrument of rebellion. It is the tool through which Dreyman can anonymously publish the truth about the GDR's hidden suicide statistics, an act of defiance against state-controlled information.

The typewriter is smuggled in from West Germany and hidden under a floorboard in Dreyman's apartment. It is used to write the explosive article for Der Spiegel. Christa-Maria reveals its location under interrogation, but Wiesler secretly removes it before the Stasi can conduct their final search, thus saving Dreyman.

The Red Ink Fingerprint

The red ink stain on the final surveillance report symbolizes Wiesler's humanity and his 'bloody' hands in both his past as a Stasi agent and his present act of saving Dreyman. It is the unintentional confession of his good deed, a human trace left within the cold, bureaucratic machine of the Stasi archives. This small, accidental mark is the clue that allows Dreyman to piece together the truth about his silent protector years later, signifying that human actions, however hidden, can leave an indelible mark.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Dreyman inspects his Stasi file. He is puzzled by the falsified reports until he sees a red fingerprint on the final entry, the same red as his typewriter's ribbon. This leads him to realize that the officer in charge, HGW XX/7, must have handled and hidden the typewriter, thereby saving him.

The Brecht Poem

The book of Bertolt Brecht's poetry that Wiesler steals from Dreyman's apartment symbolizes his burgeoning curiosity and his first active step toward engaging with the world of ideas he is monitoring. It represents a bridge between his sterile existence and the rich intellectual life of his target. Taking the book is an act of personal, quiet rebellion and a thirst for the humanism that his own life lacks.

During a moment when Dreyman and Christa-Maria are out, Wiesler, under the pretense of planting a bug, enters their apartment. He is drawn to their books and impulsively steals a volume of Brecht's poetry. He is later seen reading it alone in his bleak apartment, a stark contrast to his usual state-approved materials.

Philosophical Questions

Can art make us better people?

The film directly engages with this question through the "Sonata for a Good Man." Dreyman asks, "Can someone who has heard this music... really be a bad person?" Wiesler's transformation seems to affirm this. His exposure to Dreyman's art and lifestyle awakens his dormant empathy and leads him to a profound moral shift. The film was inspired by a quote from Lenin, who avoided Beethoven because it made him feel 'soft' when he needed to be merciless, suggesting a belief in art's power to alter one's moral compass. The film explores whether aesthetic experience is intrinsically linked to ethical behavior, suggesting that beauty can be a powerful antidote to ideology and cruelty.

What is the nature of good and evil in a totalitarian state?

"The Lives of Others" complicates simplistic notions of good and evil. Wiesler begins as an agent of an evil system but becomes a 'good man.' Christa-Maria is a victim who also becomes a betrayer under duress. Dreyman is a good man who is initially complicit through his silence. The film suggests that morality is not static but a series of choices made under specific, often extreme, pressures. It moves beyond judging characters as simply 'good' or 'bad' and instead examines their capacity for change, compromise, and courage, arguing that true morality lies in the potential for redemption and the decision to act with humanity even when the system demands otherwise.

Does privacy have an intrinsic moral value?

The film is a powerful defense of privacy, showing its absence as fundamentally dehumanizing. The constant surveillance creates a world of paranoia and emotional sterility. As Wiesler intrudes upon the private lives of Dreyman and Sieland, he is ironically humanized by what he sees and hears. Their unguarded moments of love, creativity, and despair are what transform him. The film argues that privacy is the space where authentic humanity—with all its flaws and beauties—is nurtured. Its violation by the state is not just a political act but a profound moral and spiritual one.

Core Meaning

The core meaning of "The Lives of Others" is a profound exploration of the transformative power of empathy and art in the face of a dehumanizing totalitarian regime. Director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck crafts a human drama about the ability of individuals to choose morality and do the right thing, no matter how far down the wrong path they have gone. The film posits that exposure to genuine human connection, love, and artistic expression—symbolized by literature and music—can awaken the dormant humanity in even the most hardened ideologue. It serves as a powerful testament to the idea that no system of oppression can completely extinguish the human spirit and the capacity for compassion. Ultimately, it is a story of quiet rebellion and redemption, suggesting that small, unseen acts of courage can have a profound and lasting impact.