La classe operaia va in paradiso

The Working Class Goes to Heaven - Symbolism & Philosophy

Symbols & Motifs

The Severed Finger

Symbolizes the loss of the worker's "wholeness" and the physical toll of capitalism. It is the literal piece of himself Lulù has sacrificed to the machine, triggering his realization that he is expendable.

Occurs mid-film during a period of high-speed work, serving as the narrative's turning point from compliance to radicalization.

The Fog and the Wall

Represents the barrier between the worker's grim reality and the promised "paradise" of liberation. The fog signifies the confusion and lack of clarity inherent in the class struggle.

Appears in Lulù’s final dream and the closing dialogue, where he describes breaking through a wall only to find more fog.

The Scrooge McDuck Doll

A symbol of capitalist greed and the false promises of consumerism that Lulù initially embraces and later violently rejects.

Lulù is seen destroying his belongings, including this doll, as his psychological breakdown intensifies.

The Piecework (Cottimo)

The ultimate symbol of the internal competition that destroys worker solidarity. It turns the worker against his own body and his peers.

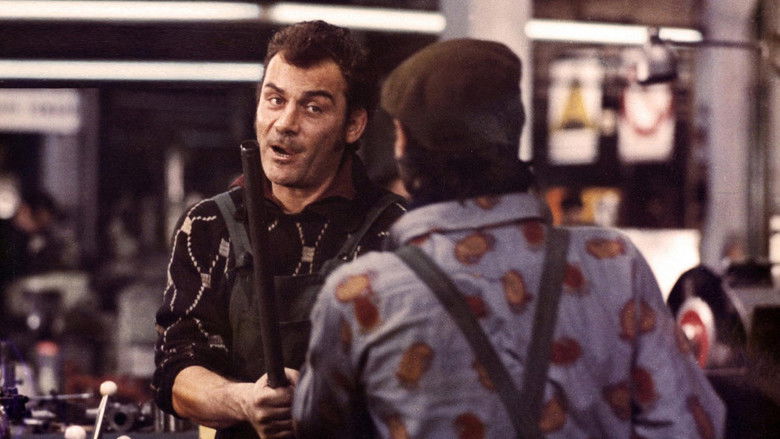

Represented by the rhythmic, cacophonous sound of the machines and Lulù’s frantic movements at the lathe.

Philosophical Questions

Can humanity survive within a system that requires individuals to function as machines?

The film explores this through Lulù's attempt to regain his libido and personality after his accident, suggesting that the industrial environment permanently alters the human psyche.

Is political consciousness possible for a worker who is physically and mentally exhausted?

Lulù's "radicalization" is portrayed as a form of hysteria or madness rather than a clear ideological awakening, questioning if the system even allows for the energy required for true liberation.

Core Meaning

The film is a searing critique of the dehumanizing nature of industrial capitalism and the failure of organized political structures to address the visceral reality of the working class. Director Elio Petri suggests that the worker is squeezed between two forms of exploitation: the economic exploitation of the bosses and the ideological exploitation of political factions who see the laborer as a symbol rather than a human being. The "paradise" in the title is a tragic irony—a distant, unreachable state beyond the fog of the factory floor.