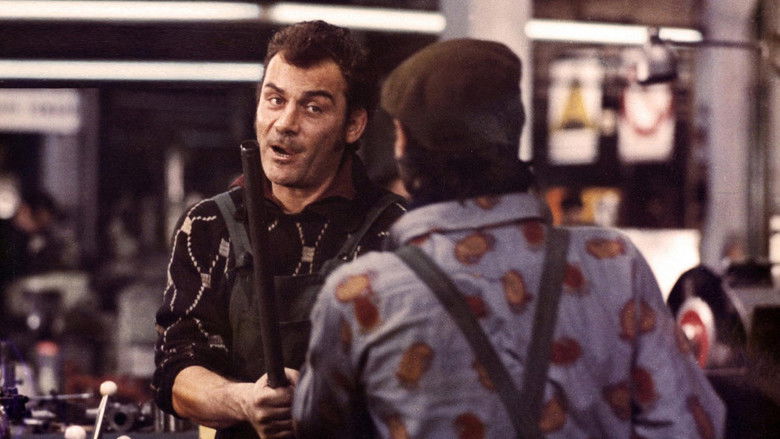

The Working Class Goes to Heaven

La classe operaia va in paradiso

Overview

Lulù Massa is the ultimate productive worker at a Milanese factory, a "Stakhanovite" whose obsession with piecework efficiency makes him a darling of management and a pariah among his colleagues. He views himself not as a man, but as a biological extension of the machinery he operates, finding a perverse, exhausting peace in the rhythmic mechanical grind that fuels his existence and funds his consumerist lifestyle.

However, Lulù's precarious equilibrium is shattered when he loses a finger in a workplace accident. This physical mutilation triggers a psychological and political awakening. No longer able to function as a perfect cog, he is thrust into the volatile landscape of the "Hot Autumn" of 1969, where he becomes a pawn in the battle between institutional unions, radical student revolutionaries, and a ruthless industrial system that views him as a disposable tool.

Core Meaning

The film is a searing critique of the dehumanizing nature of industrial capitalism and the failure of organized political structures to address the visceral reality of the working class. Director Elio Petri suggests that the worker is squeezed between two forms of exploitation: the economic exploitation of the bosses and the ideological exploitation of political factions who see the laborer as a symbol rather than a human being. The "paradise" in the title is a tragic irony—a distant, unreachable state beyond the fog of the factory floor.

Thematic DNA

Alienation and Dehumanization

Revealed through Lulù’s initial pride in being a "tool." He identifies so closely with his machine that his personal life, health, and sex drive are entirely subsumed by industrial output. The film illustrates how capitalism transforms humans into mechanical components.

The Failures of the Left

Petri satirizes both the slow, bureaucratic unions and the detached, intellectual student radicals. Neither group truly understands Lulù's existential crisis; the students use him as a revolutionary mascot while the unions eventually negotiate his return to the very machine that broke him.

Workplace Madness (The Trilogy of Neurosis)

The film explores how the repetitive, high-speed nature of piecework leads to mental collapse. This is embodied by the character Militina, a former worker whose descent into insanity serves as a prophetic mirror for Lulù’s own breakdown.

Consumerism as a Trap

Lulù's motivation for hard work is the accumulation of commodities—TVs, cars, and gadgets. The film portrays these items not as rewards, but as the chains that keep the worker tethered to the assembly line.

Character Analysis

Ludovico 'Lulù' Massa

Gian Maria Volonté

Motivation

Initially motivated by piecework bonuses and consumer status; later driven by a desperate, mad search for a sense of human dignity outside the factory.

Character Arc

Starts as a highly productive but disliked "model worker." After his injury, he transforms into a frantic activist, only to eventually be crushed back into the system, realizing his individual rebellion has changed nothing.

Lidia

Mariangela Melato

Motivation

Security, comfort, and the maintenance of a "normal" domestic life despite the chaos of the factory world.

Character Arc

Remains largely static as a representative of the domestic consumerist world. She is unable to understand Lulù’s political awakening and eventually leaves him when his instability threatens her security.

Militina

Salvo Randone

Motivation

To warn others of the factory's soul-crushing power and to find peace within his own fractured mind.

Character Arc

An institutionalized former worker who provides Lulù with the philosophical tools to understand his condition, though through the lens of madness.

Symbols & Motifs

The Severed Finger

Symbolizes the loss of the worker's "wholeness" and the physical toll of capitalism. It is the literal piece of himself Lulù has sacrificed to the machine, triggering his realization that he is expendable.

Occurs mid-film during a period of high-speed work, serving as the narrative's turning point from compliance to radicalization.

The Fog and the Wall

Represents the barrier between the worker's grim reality and the promised "paradise" of liberation. The fog signifies the confusion and lack of clarity inherent in the class struggle.

Appears in Lulù’s final dream and the closing dialogue, where he describes breaking through a wall only to find more fog.

The Scrooge McDuck Doll

A symbol of capitalist greed and the false promises of consumerism that Lulù initially embraces and later violently rejects.

Lulù is seen destroying his belongings, including this doll, as his psychological breakdown intensifies.

The Piecework (Cottimo)

The ultimate symbol of the internal competition that destroys worker solidarity. It turns the worker against his own body and his peers.

Represented by the rhythmic, cacophonous sound of the machines and Lulù’s frantic movements at the lathe.

Memorable Quotes

Un pezzo, un culo, un pezzo, un culo...

— Lulù Massa

Context:

Lulù says this while working at high speed, demonstrating his total immersion in the machine's rhythm.

Meaning:

This repetitive chant (One piece, one ass...) highlights Lulù's dehumanization, equating the production of mechanical parts with the basest human functions in a rhythmic, obsessive cycle.

Non morirai nel tuo letto, morirai qui sulla tua macchina.

— A Coworker / Militina

Context:

Used to describe the inevitable end for those who, like Lulù, give everything to the factory.

Meaning:

A grim prophecy of the worker's fate: total consumption by the industrial process until death.

Ho abbattuto il muro! E di là cosa c'era? La nebbia.

— Lulù Massa

Context:

The final lines of the film, spoken as Lulù returns to the assembly line.

Meaning:

Reveals the futility of the struggle and the lack of a clear utopian vision. Even when the "wall" is broken, there is no paradise, only more uncertainty.

Philosophical Questions

Can humanity survive within a system that requires individuals to function as machines?

The film explores this through Lulù's attempt to regain his libido and personality after his accident, suggesting that the industrial environment permanently alters the human psyche.

Is political consciousness possible for a worker who is physically and mentally exhausted?

Lulù's "radicalization" is portrayed as a form of hysteria or madness rather than a clear ideological awakening, questioning if the system even allows for the energy required for true liberation.

Alternative Interpretations

While often read as a Marxist critique, some critics argue the film is deeply pessimistic about all forms of collective action. This reading suggests that Lulù is just as much a victim of the students and unions as he is of the bosses. Another interpretation focuses on the film as a psychoanalytic study, where the factory represents the Id and the piecework is a form of masturbatory obsession that eventually leads to castration (the lost finger).

Cultural Impact

Released during Italy's "Years of Lead," the film served as a lightning rod for political debate. It challenged the prevailing cinematic depictions of the working class, which were often romanticized or overly heroic. Instead, Petri presented a raw, vulgar, and psychologically fractured worker. It influenced the "Cinema di Impegno" (cinema of social commitment) and paved the way for the satirical social dramas of Lina Wertmüller. Today, it is regarded as one of the most important political films ever made, accurately capturing the tension between labor, capitalism, and political dogma.

Audience Reception

The film was a massive box-office success in Italy, as working-class audiences flocked to see a realistic, if harsh, depiction of their lives. Critics were more divided; while many praised Volonté's powerhouse performance and Petri's stylistic audacity, hardline leftist critics accused the film of being counter-revolutionary due to its depiction of worker neurosis and the ineffectiveness of the students.

Interesting Facts

- Gian Maria Volonté prepared for the role by working in a real metal factory in Novara for a month to learn the machines' rhythms.

- The film shared the Palme d'Or (then called Grand Prix International du Festival) at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival with 'The Mattei Affair'.

- It is the second film in Elio Petri's 'Trilogy of Neurosis,' following 'Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion' (1970) and preceding 'Property Is No Longer a Theft' (1973).

- Director Elio Petri and star Gian Maria Volonté were both committed leftists who were often arrested together during political protests in Italy.

- The film was highly controversial among the Italian Left; filmmaker Jean-Marie Straub reportedly suggested the film should be burned because it portrayed workers as neurotic.

- The film's American title was changed to 'Lulu the Tool' to emphasize the protagonist's status as an object of industry.

Easter Eggs

Ennio Morricone Cameo

The legendary composer Ennio Morricone makes a brief appearance in the film. This is a rare on-screen moment for the maestro who provided the film's iconic, mechanical score.

Bruegel Visual Reference

The scene where police pursue protesters through the snow is a visual homage to Pieter Bruegel the Elder's 1565 painting 'The Hunters in the Snow,' contrasting the beauty of the landscape with the violence of the state.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!