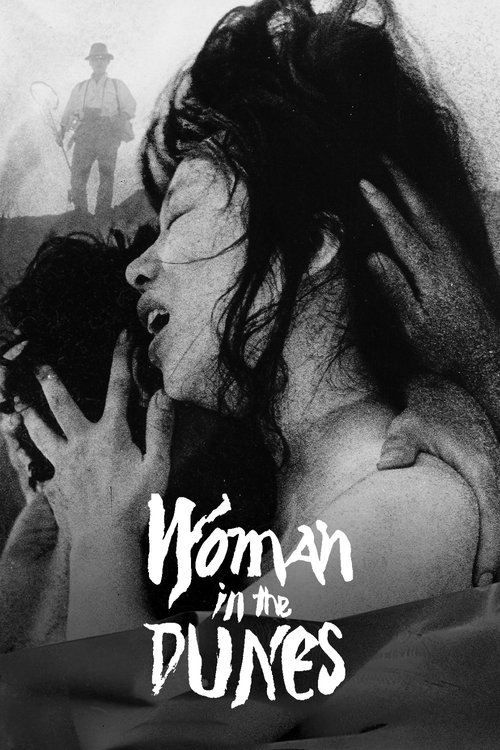

砂の女

"Haunting. Erotic. Unforgettable."

Woman in the Dunes - Symbolism & Philosophy

Symbols & Motifs

Sand

Sand is the film's dominant symbol, representing the overwhelming, oppressive forces of existence, time, and society. It is both constant and ever-shifting, embodying the futility of fighting against the inevitable. Its ceaseless movement suggests the transitory nature of reality. It is also a paradoxical substance: it is life-threatening, constantly threatening to bury the characters, yet it is also the source of their livelihood and, eventually, for Junpei, a source of scientific discovery (water).

The sand is omnipresent throughout the film. It cascades into the pit, covers the characters' bodies, gets into their food, and defines their labor. The microscopic close-ups of sand grains give it a terrifying, alien quality. The daily act of shoveling sand is the central, Sisyphean task that shapes the entire narrative and the characters' existence.

Insects

Insects symbolize humanity's struggle for existence and the relationship between the observer and the observed. Junpei begins as an entomologist, a collector who traps and pins insects for study, viewing them with detached superiority. His goal is to get his name in a field guide, a desire for tangible recognition. In an ironic twist, he becomes like one of his specimens—trapped in a strange environment, observed by the villagers, and studied by the audience.

The film opens with Junpei hunting for a specific type of beetle. His passion for collecting insects leads him into the trap. The antlion, which traps its prey in a sand pit, is a direct parallel to Junpei's own situation. His transformation is complete when he ceases to be the collector and fully becomes the collected, finding a new purpose within his new habitat.

The Rope Ladder

The rope ladder symbolizes the fragile and often arbitrary connection to the outside world and to conventional notions of freedom. It represents the means of escape, the path back to a former life. Its presence or absence dictates the protagonist's status as a guest or a prisoner.

Junpei descends the ladder willingly at the start of the film, believing he is a guest. Its removal the next morning signifies his entrapment. Throughout the film, the ladder remains the villagers' primary tool of control. When, at the end, the ladder is left behind and Junpei has a clear chance to escape, his choice not to climb it signifies that it no longer holds symbolic power over him; he has found a different kind of freedom where he is.

Water

Water symbolizes life, hope, and control. In the arid, sand-dominated environment, water is a scarce and precious commodity. It is a tool used by the villagers to control the man and woman, who depend on them for their supply. Later, Junpei's discovery of a way to extract water from the sand represents a reclamation of agency, a form of intellectual and existential liberation that makes physical escape less important.

The villagers provide water in exchange for the sand that is shoveled. They withhold it as a punishment when Junpei rebels. The sensuous bathing scenes highlight water's life-affirming and erotic qualities in the oppressive environment. Junpei's invention of a water-trap is the climax of his intellectual journey, giving him a newfound purpose and a measure of independence from his captors.

Philosophical Questions

What is the true nature of freedom?

The film relentlessly interrogates the concept of freedom by contrasting Junpei's life before and after his capture. Is freedom merely the ability to move without physical restraint, or is it a state of mind? His life in Tokyo was governed by timetables, paperwork, and societal expectations—a different kind of trap. In the pit, though physically confined, he is stripped of these modern constraints and lives a more primal existence. The film culminates in him having the physical freedom to leave but choosing to stay, suggesting that he has found a higher form of freedom: the freedom that comes from creating one's own purpose, independent of societal norms or physical location.

Can one find meaning in a meaningless existence?

This is the central question of absurdism that the film explores. The task of shoveling sand is objectively pointless and unending, a perfect metaphor for an absurd existence. Junpei's initial response is despair and rebellion. However, following the teachings of Albert Camus, the film shows a path to overcoming this despair. By ceasing his fight against the inevitable and instead focusing his intellect on a problem within his environment (the water trap), Junpei creates meaning. The film's answer is a resounding yes: meaning is not discovered, but created through conscious engagement with one's struggle.

What is the relationship between the individual and society?

The film presents a stark conflict between individual desire and the needs of the community. Junpei, an emblem of modern individualism, is sacrificed for the collective good of the village. The villagers operate on a ruthless pragmatism where the survival of the group justifies the enslavement of an individual. Junpei's journey is one of forced integration, moving from a self-centered perspective to becoming an essential part of a small, struggling society. This raises questions about the obligations an individual has to the community and the price society can exact for its own preservation.

Core Meaning

At its core, "Woman in the Dunes" is a powerful existential allegory about the human condition. Director Hiroshi Teshigahara, adapting Kōbō Abe's novel, explores the tension between individual freedom and societal obligation, and the search for meaning in a seemingly absurd world. The film questions the very definition of freedom; is Junpei's former life in the bureaucratic, rule-bound city truly more liberating than his primal existence in the pit?

The film suggests that meaning is not found in escaping one's circumstances, but in creating purpose within them. Junpei's initial struggle is for escape, but his journey transforms into one of adaptation and discovery. He eventually finds a new sense of purpose not in returning to his old life, but in a scientific breakthrough within his confinement—a method to extract water from the sand. This mirrors the philosophy of absurdism, particularly Camus's concept of Sisyphus finding happiness in his struggle. The film posits that true freedom is not the absence of constraints, but the conscious choice to find meaning and purpose within them.