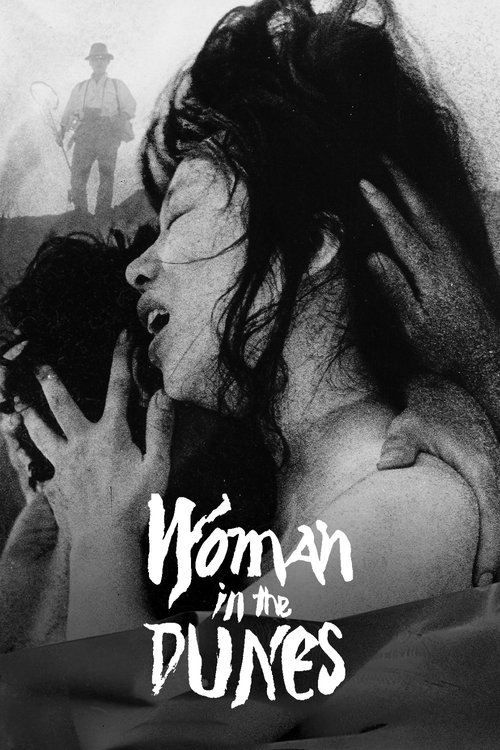

Woman in the Dunes

砂の女

"Haunting. Erotic. Unforgettable."

Overview

"Woman in the Dunes" is a Japanese New Wave classic that follows Niki Junpei, an amateur entomologist from Tokyo on a trip to collect insects in a vast coastal desert. After missing the last bus back to the city, villagers offer him a place to stay for the night. They lead him down a rope ladder to a house situated at the bottom of a deep sand pit, where a lone widow lives.

The following morning, Junpei discovers the rope ladder has been removed, realizing he is trapped. The villagers expect him to assist the woman in her Sisyphean task: shoveling the constantly encroaching sand that threatens to bury the house. This sand is sold by the village, making their labor essential for the community's survival. Initially, Junpei rebels, clinging to his identity and plotting various escapes, but the relentless sand and the woman's resigned acceptance of her fate begin to erode his will.

A complex, often erotic, and tense relationship develops between the man and the woman, two captives in a bizarre microcosm. As days turn into weeks, Junpei's struggle against his captors and his environment forces him to confront the fundamental nature of freedom, identity, and the meaning of existence itself.

Core Meaning

At its core, "Woman in the Dunes" is a powerful existential allegory about the human condition. Director Hiroshi Teshigahara, adapting Kōbō Abe's novel, explores the tension between individual freedom and societal obligation, and the search for meaning in a seemingly absurd world. The film questions the very definition of freedom; is Junpei's former life in the bureaucratic, rule-bound city truly more liberating than his primal existence in the pit?

The film suggests that meaning is not found in escaping one's circumstances, but in creating purpose within them. Junpei's initial struggle is for escape, but his journey transforms into one of adaptation and discovery. He eventually finds a new sense of purpose not in returning to his old life, but in a scientific breakthrough within his confinement—a method to extract water from the sand. This mirrors the philosophy of absurdism, particularly Camus's concept of Sisyphus finding happiness in his struggle. The film posits that true freedom is not the absence of constraints, but the conscious choice to find meaning and purpose within them.

Thematic DNA

Existentialism and Absurdism

The film is a profound exploration of existentialist philosophy, confronting the protagonist with a meaningless, repetitive task akin to the myth of Sisyphus. Junpei is forced to question the purpose of his existence when faced with the absurd task of endlessly shoveling sand. His journey reflects the existential search for meaning in a universe devoid of inherent purpose. Initially, he rebels against the absurdity, but he eventually finds a form of liberation not through escape, but through accepting his situation and creating his own meaning within it, embodying the concept of the 'absurd hero'.

Freedom vs. Captivity

The film constantly blurs the line between freedom and imprisonment. While Junpei is physically trapped in the pit, the narrative questions whether his life in modern Tokyo, with its stifling routines and societal pressures, was any more free. The woman, though also a captive, has accepted her fate and found a way to live within it. Ultimately, the film suggests that freedom is a state of mind rather than a physical reality. Junpei's final decision to stay in the pit, even when escape is possible, signifies a shift in his understanding of freedom—he chooses his new purpose over the hollow liberty of his past.

Individual vs. Community

Junpei, the alienated city-dweller, is thrust into a primal community with its own strange rules and logic. His struggle is initially against the villagers who have trapped him for their collective survival. They represent a society that prioritizes the group's needs over individual liberty. The woman embodies a submission to the community's will for the sake of survival. Over time, Junpei's relationship with the woman and his forced role in the community's labor transform him from an isolated individual into a participant, however reluctant, in a collective struggle.

Identity and Transformation

Junpei's identity as a schoolteacher and entomologist is stripped away by his ordeal. His documents and connections to the outside world become meaningless. In the pit, he is reduced to his most basic functions: to work, eat, sleep, and procreate. This forces a profound transformation; he sheds the trappings of his former self and discovers a new, more fundamental identity rooted in survival, purpose, and human connection. His final choice to remain is the culmination of this transformation, as he no longer identifies with the man who first entered the dunes.

Character Analysis

Niki Junpei

Eiji Okada

Motivation

Initially, his motivation is singular: to escape and return to his life in Tokyo, reclaiming his freedom and identity. As the film progresses, this motivation is replaced by a more complex set of needs: survival, companionship with the woman, and ultimately, the pursuit of a new purpose he discovers within the pit—the intellectual challenge of his water-trap invention.

Character Arc

Junpei begins as an alienated, arrogant schoolteacher from the city, seeking a small form of immortality by discovering a new insect. Trapped in the pit, he goes through stages of denial, rage, and desperate rebellion. He initially views the woman and the villagers with contempt. Over time, the harsh reality of his situation erodes his intellectual superiority and forces him into a primal state of existence. His focus shifts from escape to adaptation and, finally, to creation. By discovering a way to find water, he finds a new meaning that transcends his desire for his old life, and he chooses to stay when given the chance to leave, completing his transformation from a captive to a willing resident.

The Woman

Kyôko Kishida

Motivation

Her motivation is pure survival and the fulfillment of her duty to the community. She shovels sand to protect her home and receive rations. She seems to desire companionship, accepting Junpei's presence as a pragmatic necessity that evolves into a genuine, if complex, bond. Her deepest-held wish is for a radio, a simple connection to the outside world she knows she can never rejoin.

Character Arc

The Woman has little to no arc in the traditional sense; she is a constant, representing acceptance and resilience. Having already lost her husband and child to a sandstorm, she has long since resigned herself to her fate and the endless work required to survive. She is simple, sensual, and deeply connected to her harsh environment. She doesn't question her circumstances but works to live within them. While Junpei undergoes a radical transformation, she remains the stable center of their world, teaching him through her example that one can find a way to live, and even love, in the most oppressive conditions.

The Villagers

Kōji Mitsui, etc.

Motivation

The villagers' sole motivation is the survival of their community. The encroaching sand is an existential threat, and their harsh methods—including trapping outsiders for labor—are a means to an end. They sell the sand to construction companies to earn their livelihood. Their actions are driven by a collective, pragmatic desperation.

Character Arc

The villagers act as a collective entity and do not have individual arcs. They function as both Junpei's captors and the arbiters of his fate, resembling a Greek chorus that observes and controls the action from above. Their morality is pragmatic and born of necessity; they trap Junpei not out of pure malice, but because they need his labor for the village to survive. They are insular and indifferent to the outside world's ethics, enforcing their own rules for survival.

Symbols & Motifs

Sand

Sand is the film's dominant symbol, representing the overwhelming, oppressive forces of existence, time, and society. It is both constant and ever-shifting, embodying the futility of fighting against the inevitable. Its ceaseless movement suggests the transitory nature of reality. It is also a paradoxical substance: it is life-threatening, constantly threatening to bury the characters, yet it is also the source of their livelihood and, eventually, for Junpei, a source of scientific discovery (water).

The sand is omnipresent throughout the film. It cascades into the pit, covers the characters' bodies, gets into their food, and defines their labor. The microscopic close-ups of sand grains give it a terrifying, alien quality. The daily act of shoveling sand is the central, Sisyphean task that shapes the entire narrative and the characters' existence.

Insects

Insects symbolize humanity's struggle for existence and the relationship between the observer and the observed. Junpei begins as an entomologist, a collector who traps and pins insects for study, viewing them with detached superiority. His goal is to get his name in a field guide, a desire for tangible recognition. In an ironic twist, he becomes like one of his specimens—trapped in a strange environment, observed by the villagers, and studied by the audience.

The film opens with Junpei hunting for a specific type of beetle. His passion for collecting insects leads him into the trap. The antlion, which traps its prey in a sand pit, is a direct parallel to Junpei's own situation. His transformation is complete when he ceases to be the collector and fully becomes the collected, finding a new purpose within his new habitat.

The Rope Ladder

The rope ladder symbolizes the fragile and often arbitrary connection to the outside world and to conventional notions of freedom. It represents the means of escape, the path back to a former life. Its presence or absence dictates the protagonist's status as a guest or a prisoner.

Junpei descends the ladder willingly at the start of the film, believing he is a guest. Its removal the next morning signifies his entrapment. Throughout the film, the ladder remains the villagers' primary tool of control. When, at the end, the ladder is left behind and Junpei has a clear chance to escape, his choice not to climb it signifies that it no longer holds symbolic power over him; he has found a different kind of freedom where he is.

Water

Water symbolizes life, hope, and control. In the arid, sand-dominated environment, water is a scarce and precious commodity. It is a tool used by the villagers to control the man and woman, who depend on them for their supply. Later, Junpei's discovery of a way to extract water from the sand represents a reclamation of agency, a form of intellectual and existential liberation that makes physical escape less important.

The villagers provide water in exchange for the sand that is shoveled. They withhold it as a punishment when Junpei rebels. The sensuous bathing scenes highlight water's life-affirming and erotic qualities in the oppressive environment. Junpei's invention of a water-trap is the climax of his intellectual journey, giving him a newfound purpose and a measure of independence from his captors.

Memorable Quotes

Are you shoveling to survive, or surviving to shovel?

— Niki Junpei

Context:

This is said during one of Junpei's early periods of frustration and rebellion, as he tries to make the woman see the futility of her unquestioning acceptance of their fate. He cannot yet understand her resignation and is desperately trying to cling to the idea that life must have a purpose beyond endless, seemingly pointless toil.

Meaning:

This question encapsulates the central existential crisis of the film. Junpei poses it to the woman, challenging the seeming meaninglessness of their repetitive labor. It probes the difference between work as a means to an end (survival) and work becoming the end itself, a cyclical, absurd existence. It is the question every person in a monotonous, modern society might ask themselves.

If you were to give up a fixed position and abandon yourself to the movement of the sands, competition would soon stop.

— Niki Junpei (voiceover, from the novel)

Context:

This realization occurs late in the narrative, after Junpei has stopped fighting his circumstances. It signifies his intellectual and spiritual surrender to his environment, a move from resistance to adaptation. He begins to see the sand not just as an enemy but as a force with its own laws, which one can live with rather than against.

Meaning:

This quote, more explicit in the novel, reflects Junpei's ultimate philosophical shift. It suggests that struggle, anxiety, and conflict arise from clinging to a fixed identity and resisting the inevitable flow of life (symbolized by the sand). By accepting fluidity and change, one can find a form of peace and escape the 'competition' of a goal-oriented, conventional life.

Without the threat of punishment, there is no joy in flight.

— Niki Junpei (voiceover, from the novel)

Context:

This thought comes to Junpei as he contemplates his situation. It foreshadows his eventual indifference to escape. When the ladder is finally available and there is no one to stop him, the 'flight' has lost its meaning. The joy was in the struggle against his captors, not in the simple act of leaving.

Meaning:

This quote explores the paradoxical nature of freedom. It implies that the desire to escape is defined and given value by the very existence of captivity. Freedom is not an absolute state but is rendered meaningful by its opposite. Once the possibility of punishment or failure is removed, the act of escaping loses its thrill and, perhaps, its purpose.

Philosophical Questions

What is the true nature of freedom?

The film relentlessly interrogates the concept of freedom by contrasting Junpei's life before and after his capture. Is freedom merely the ability to move without physical restraint, or is it a state of mind? His life in Tokyo was governed by timetables, paperwork, and societal expectations—a different kind of trap. In the pit, though physically confined, he is stripped of these modern constraints and lives a more primal existence. The film culminates in him having the physical freedom to leave but choosing to stay, suggesting that he has found a higher form of freedom: the freedom that comes from creating one's own purpose, independent of societal norms or physical location.

Can one find meaning in a meaningless existence?

This is the central question of absurdism that the film explores. The task of shoveling sand is objectively pointless and unending, a perfect metaphor for an absurd existence. Junpei's initial response is despair and rebellion. However, following the teachings of Albert Camus, the film shows a path to overcoming this despair. By ceasing his fight against the inevitable and instead focusing his intellect on a problem within his environment (the water trap), Junpei creates meaning. The film's answer is a resounding yes: meaning is not discovered, but created through conscious engagement with one's struggle.

What is the relationship between the individual and society?

The film presents a stark conflict between individual desire and the needs of the community. Junpei, an emblem of modern individualism, is sacrificed for the collective good of the village. The villagers operate on a ruthless pragmatism where the survival of the group justifies the enslavement of an individual. Junpei's journey is one of forced integration, moving from a self-centered perspective to becoming an essential part of a small, struggling society. This raises questions about the obligations an individual has to the community and the price society can exact for its own preservation.

Alternative Interpretations

While the dominant interpretation of the ending is one of existential acceptance—that Junpei finds true purpose and freedom within his confinement—other readings exist.

One darker interpretation is that Junpei's will has been completely broken by his captors. His decision to stay isn't a triumphant choice but the final act of submission. In this view, he has succumbed to a form of Stockholm Syndrome, rationalizing his imprisonment by inventing a purpose (the water pump) to make his defeat palatable. The final shot, revealing he has been officially missing for seven years, seals his fate as a man erased by an oppressive system, a tragic victim rather than an 'absurd hero'.

Another perspective focuses on the social commentary. The villagers could be seen as a metaphor for Japan's marginalized communities, such as the *burakumin*, who have been historically ostracized. Their desperate actions are a response to being abandoned by the larger society. Junpei's integration could then be seen as an allegory for the individual being absorbed into a collective struggle, losing his selfish desires in favor of a communal goal, which could be read as either a positive or negative outcome depending on one's perspective on collectivism versus individualism.

Cultural Impact

"Woman in the Dunes" was a sensation of the international art-house circuit in the 1960s and a cornerstone of the Japanese New Wave. Released the same year as the Tokyo Olympics, a time of rapid modernization in Japan, the film offered a stark, allegorical critique of the dehumanizing aspects of modern life, conformity, and the relentless nature of labor. Some analyses suggest the film's context relates to the arduous Japanese work culture that would later be associated with 'Karoshi' (death from overwork).

Its philosophical depth, heavily influenced by Western existentialists like Albert Camus and Franz Kafka, resonated with international audiences and critics, making Kōbō Abe one of Japan's most celebrated and translated authors. The film's depiction of a Sisyphean struggle is often compared to Camus's famous essay "The Myth of Sisyphus." Its masterful, claustrophobic cinematography and the tangible, tactile quality of the sand have been widely influential, with critic Roger Ebert noting, "There has never been sand photography like this." The film's success, including its Special Jury Prize at Cannes and two Oscar nominations, brought significant international attention to its director and to Japanese cinema beyond the established masters like Kurosawa and Ozu.

Audience Reception

Audiences often describe "Woman in the Dunes" as a haunting, hypnotic, and unforgettable experience. Praise is almost universally directed at its stunning, tactile black-and-white cinematography, with many viewers noting how the sand itself becomes a character. The film's thick, claustrophobic atmosphere and Toru Takemitsu's unsettling score are frequently highlighted as masterful elements that create a palpable sense of dread and tension. The performances of Eiji Okada and Kyôko Kishida are celebrated for their intensity and nuance.

Points of criticism or difficulty for some viewers often revolve around the film's deliberate pacing and its bleak, allegorical nature, which can feel mentally taxing. The story's inherent ambiguity, especially the ending, leads to extensive debate but can leave some viewers desiring a more concrete resolution. The eroticism, while critically noted for its effectiveness, is raw and sometimes disturbing, contributing to the film's overall harrowing feel. Despite these challenges, the overwhelming verdict is that it is a profound and powerful masterpiece of world cinema.

Interesting Facts

- The film was nominated for two Academy Awards: Best Foreign Language Film in 1965 and Best Director for Hiroshi Teshigahara in 1966, a rare accomplishment for a Japanese director at the time.

- Director Hiroshi Teshigahara was a master of the Sogetsu school of *ikebana* (Japanese flower arrangement), and his artistic sensibility for texture, form, and natural materials is evident in the film's stunning visuals.

- The screenplay was written by Kōbō Abe, who adapted it from his own 1962 novel of the same name.

- The film was a collaboration between Teshigahara, writer Kōbō Abe, and composer Toru Takemitsu, who worked together on several films.

- The sensual and erotic scenes were considered quite daring for mainstream Japanese cinema in the early 1960s.

- Roger Ebert added the film to his "Great Movies" list, praising its unparalleled sand photography and its power as a parable.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!