Cidade de Deus

"If you run, the beast catches you; if you stay, the beast eats you."

City of God - Symbolism & Philosophy

Symbols & Motifs

The Camera

The camera symbolizes perspective, truth, and a non-violent form of power. It represents Rocket's 'eye' on the world, a tool that allows him to distance himself from the chaos and document it objectively. It is his weapon of choice, offering him a means of escape and a way to tell the story of his community without being consumed by its violence.

Rocket uses his camera throughout the film to capture life in the City of God. Initially a hobby, it becomes his profession and his salvation. A pivotal moment is when his photographs of Li'l Zé and the gang are published in a newspaper, bringing him recognition and an opportunity to leave. In the final sequence, the actor playing Rocket actually operates the camera, blurring the line between character and creator.

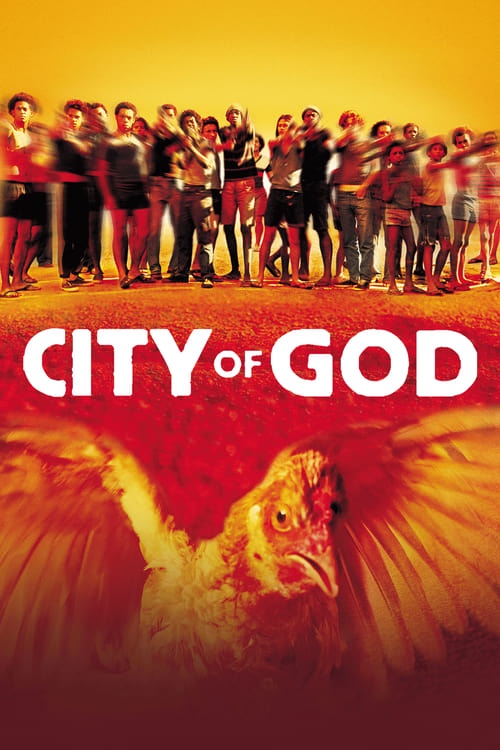

The Runaway Chicken

The chicken symbolizes the residents of the City of God, trapped in a violent environment with no easy escape. The film's tagline, "If you run, the beast catches you; if you stay, the beast eats you," is embodied by the chicken's plight. It is a symbol of survival, desperation, and the chaotic energy of the favela, where a simple chase can escalate into a deadly confrontation.

The film opens and closes with the intense chase of a chicken. In the opening scene, Rocket finds himself caught between Li'l Zé's gang and the police, with the chicken at the center of the standoff. This framing device immediately immerses the audience in the unpredictable and dangerous life of the favela.

The Apartment

The apartment symbolizes the changing power dynamics and the relentless cycle of crime within the City of God. Its ownership is a barometer of who is in control of the drug trade. The stylistic sequence showing its rapid turnover of inhabitants highlights the fleeting nature of power and life in the favela.

The film features a memorable montage titled "The Story of the Apartment." Through a fixed camera position, we see the apartment change hands from the Tender Trio to various drug dealers, culminating with Li'l Zé taking it over. The rapid changes in decor and occupants, often through violent means, visually represent the brutal succession of criminal power.

Philosophical Questions

Are we products of our environment, or do we have the free will to overcome our circumstances?

The film explores this question through the starkly different paths of Rocket and Li'l Zé. Both grew up in the same impoverished and violent environment. Li'l Zé fully succumbs to and eventually embodies the brutality of the City of God, his choices seemingly predetermined by his sociopathic nature and the opportunities crime provides. Rocket, however, actively resists this path, clinging to his dream of photography. His eventual success suggests that individual will and passion can carve a path out of seemingly inescapable circumstances. Yet, the overwhelming number of characters who are consumed by the cycle of violence raises the question of whether Rocket is the exception that proves the rule—a rare survivor in a system designed for failure.

What is the nature of power and how does it corrupt?

"City of God" provides a raw case study in the acquisition and maintenance of power in a lawless society. Li'l Zé's rise is built entirely on fear and violence. Once he achieves absolute control, his power manifests as paranoia and sadistic cruelty, such as forcing children to kill each other. Knockout Ned's arc also explores this, as his righteous quest for vengeance slowly transforms him into a killer, demonstrating that even power sought for noble reasons can lead to moral decay within the corrupting influence of war and violence.

What is the role of the observer in a world of violence and injustice?

Rocket's character embodies the dilemma of the witness. His camera allows him to document the atrocities around him, but it also keeps him at a distance. The film questions whether simply recording injustice is enough. When his photos are published, they bring him personal success but do little to change the fundamental reality of the favela. This raises philosophical questions about journalistic ethics and whether capturing suffering for an audience is a form of exploitation or a necessary act of bearing witness.

Core Meaning

"City of God" serves as a powerful and unflinching examination of the systemic nature of poverty and violence. Director Fernando Meirelles sought to portray the "casual nature" of violence in the favelas, avoiding glamorization to present a raw, authentic depiction of a world where crime is one of the only viable paths to power and survival. The film's core message revolves around the cyclical nature of violence; as one generation of gangsters falls, a younger, often more ruthless, one rises to take its place. It explores the profound impact of environment on individual destiny, contrasting the struggle to maintain humanity and pursue dreams, as seen in Rocket's journey, with the magnetic pull of the criminal underworld that consumes so many others. Ultimately, it is a commentary on social neglect and the desperate search for identity and escape in a world with seemingly no exit.