"There can be no understanding between the hands and the brain unless the heart acts as mediator."

Metropolis - Symbolism & Philosophy

Symbols & Motifs

The Tower of Babel

The Tower of Babel symbolizes the hubris and ambition of the ruling class and the disastrous disconnect between the planners and the laborers. Joh Fredersen's central office building is even named the "New Tower of Babel." In Maria's sermon, she uses the biblical story to illustrate how a great vision can fail when the "head" (the dreamers) and the "hands" (the builders) do not understand or care for one another, speaking different languages of purpose and experience.

The symbol is most explicitly used during Maria's sermon to the workers in the catacombs. She narrates the ancient legend as a direct parallel to their own situation in Metropolis, explaining why a mediator is needed to bridge the gap between the thinkers and the workers.

The Moloch Machine

The Moloch machine symbolizes the dehumanizing, sacrificial nature of industrial capitalism. Moloch is an ancient deity associated with child sacrifice. In the film, this machine consumes workers, representing how the industrial system feeds on human life for its own sustenance. It is the embodiment of technology as a monstrous, oppressive force.

Early in the film, Freder witnesses a horrific explosion at a massive machine. Overwhelmed, he has a terrifying hallucination where the machine transforms into the monstrous, temple-like head of Moloch, with workers being fed into its fiery maw. This vision awakens him to the true horror of the workers' existence.

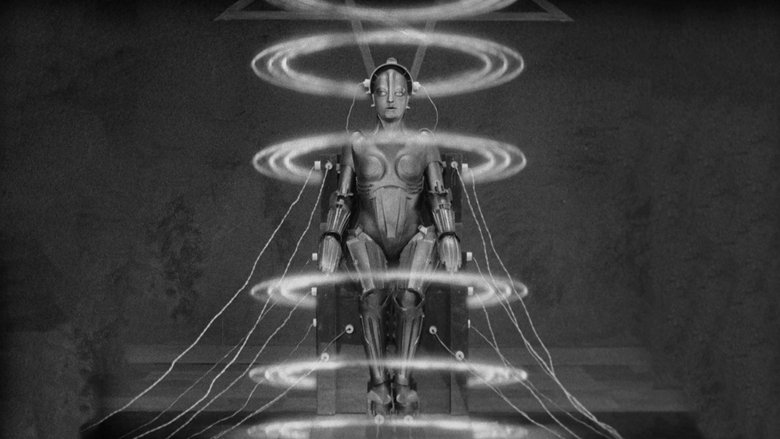

The Machine-Man (Maschinenmensch)

The Machine-Man, particularly in its guise as the false Maria, symbolizes the seductive and destructive potential of technology when devoid of a soul or heart. It represents the duality of creation: technology can be a tool for progress or a catalyst for chaos. The robot is both a scientific marvel and a monstrous perversion of humanity, capable of inciting lust, riot, and ruin.

The robot is created by Rotwang, initially as a resurrection of his lost love, Hel. Joh Fredersen commands him to give it Maria's likeness to sow discord. Its transformation is a key sequence. As the false Maria, it performs a seductive dance for the upper class and later preaches violent revolution to the workers, leading them to destroy the city's machines.

The Pentagram

The pentagram symbolizes the occult, dark, and unnatural forces associated with Rotwang's science. In contrast to the Christian crosses behind the real Maria in the catacombs, the pentagram marks Rotwang's laboratory as a place of anti-religious and dangerous creation. It visually aligns his technological prowess with black magic, suggesting his creation of the Machine-Man is a transgression against the natural order.

A large, glowing pentagram is prominently displayed on the wall of Rotwang's laboratory, notably behind the Machine-Man as it sits inanimate. This symbol is present during the robot's creation and transformation, framing the act as something mystical and sinister.

Philosophical Questions

What is the role of technology in human society, and can it exist without dehumanizing its creators?

The film portrays technology as a double-edged sword. On one hand, it creates the magnificent city of Metropolis; on the other, it enslaves the working class, turning them into extensions of the machinery. The Moloch machine represents technology as a monstrous, sacrificial god. The Machine-Man further explores this by showing how technology can perfectly imitate humanity but lack a soul, becoming a tool for immense destruction. Metropolis asks whether humanity can control its creations or if it is destined to be controlled by them, suggesting that technology without a guiding "heart" or moral compass leads inevitably to oppression and disaster.

Can true reconciliation between social classes be achieved without fundamentally altering the structure of power?

The film's central message advocates for mediation and empathy—the "heart"—to unite the ruling "head" and the working "hands." However, the conclusion is ambiguous on this point. Joh Fredersen agrees to cooperate, but he remains the master of Metropolis. The workers gain a voice, but the system of inequality is not dismantled. The film raises the question of whether a change of heart in the powerful is enough to create lasting justice, or if it's a naive solution that papers over the cracks of a fundamentally broken and exploitative system.

What is the relationship between individual identity and the collective mob?

Metropolis contrasts the individual's journey with the actions of the masses. Freder's individual awakening drives the narrative of reconciliation. The workers, however, are often shown as a faceless, uniform collective, easily swayed from passive suffering to destructive rage by a charismatic leader. The film explores how quickly a crowd can become a mindless mob, losing all reason in a frenzy of destruction, as seen when they celebrate wrecking the machines while their children are drowning. It questions the nature of collective action and warns of its potential to become an irrational force, divorced from the well-being of the individuals within it.

Core Meaning

The central message of Fritz Lang's Metropolis is encapsulated in its final intertitle: "The Mediator Between the Head and the Hands Must Be the Heart." This theme posits that for a society to function harmoniously, there must be a compassionate and empathetic connection between the ruling class (the "head," or thinkers) and the working class (the "hands," or laborers). The film critiques the dehumanizing effects of industrialization and unchecked capitalism, which create a vast chasm between the classes. It argues against both totalitarian oppression and chaotic, destructive revolution, suggesting instead a path of mutual understanding and cooperation. Ultimately, the film serves as a moral fable, advocating for humanity and empathy to bridge societal divides, portraying love and compassion as the essential forces needed to unite a fractured world.