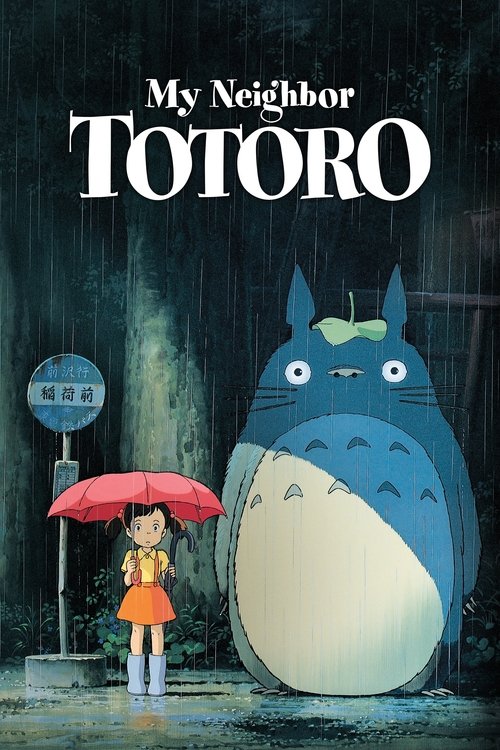

となりのトトロ

"He's your friendly neighbourhood forest spirit!"

My Neighbor Totoro - Symbolism & Philosophy

Symbols & Motifs

Totoro

Totoro symbolizes the spirit of the forest, a benevolent guardian of nature who is both powerful and gentle. He represents a comforting and protective force for the children, appearing in moments of need or wonder. His existence embodies the magic and mystery of the natural world that is accessible only to the pure-hearted and innocent.

Mei is the first to discover Totoro sleeping in the hollow of a giant camphor tree. He later appears at the bus stop in the rain with Satsuki, shares a magical dance to make seeds sprout into a giant tree overnight, and ultimately summons the Catbus to help Satsuki find the lost Mei.

The Great Camphor Tree

The ancient camphor tree is a powerful symbol of nature's enduring presence and spirituality. In Shintoism, such large, old trees are considered sacred (shinboku), often adorned with a shimenawa rope to denote the presence of a deity. It represents a gateway between the human and spirit worlds, a source of life, and a symbol of stability and ancient wisdom.

The tree dominates the landscape near the girls' new house. It is where Totoro and the other spirits live. After Mei's first encounter, her father takes both daughters to the tree to pay their respects, telling them, 'Trees and people used to be good friends.' This act formalizes the family's respectful relationship with nature.

Catbus (Nekobasu)

The Catbus is a manifestation of pure, whimsical imagination. It represents a magical solution to earthly problems and the boundless possibilities when one believes in the fantastical. It symbolizes a bridge between places, between anxiety and relief, and between the human and spirit worlds, serving as a friendly and powerful ally.

The Catbus first appears to Satsuki and Mei at the bus stop, carrying Totoro. Later, when Mei is lost, a desperate Satsuki begs Totoro for help. He summons the Catbus, which enthusiastically whisks Satsuki across the countryside, its destination sign changing to 'MEI', to find her sister and then take them to the hospital to see their mother.

Soot Sprites (Susuwatari)

The Susuwatari, or 'wandering soot,' symbolize the initial fear of the unknown that comes with a new and unfamiliar place. They are shy, harmless creatures that inhabit empty spaces. Their departure signifies that the house has been filled with life and laughter, and that the family has made the new space their own, transforming fear into comfort.

Upon arriving at their new, dilapidated house, Satsuki and Mei discover swarms of these black, fuzzy creatures in the dark corners and attic. Granny explains they are harmless and will leave once they get used to the family's presence. Later, the family sees the soot sprites flying out of the house and towards the camphor tree, indicating their acceptance of the new residents.

Acorns

Acorns function as a currency of friendship and a symbol of potential and growth. They are the first sign of the spirits' presence and act as gifts from Totoro, initiating the bond between him and the children. They represent the seeds of magic and the promise of future wonders.

Mei first follows the trail of acorns left by the smaller Totoros, which leads her to the great camphor tree. Later, at the bus stop, Totoro gives the girls a small, magical bundle of nuts and seeds in return for sharing their umbrella. The girls plant these seeds, and Totoro later helps them magically grow into a giant tree for a single night.

Philosophical Questions

What is the relationship between imagination and reality, especially during hardship?

The film explores whether the magical events are 'real' or a product of the girls' imaginations as a coping mechanism for their mother's illness. Tatsuo, their father, treats their encounters as real, suggesting that the subjective reality of a child is as valid as an adult's objective one. The film doesn't provide a definitive answer, implying that the distinction is unimportant. The power of their belief, whether real or imagined, is what gives them the strength to endure their anxieties and ultimately leads to the resolution of their immediate crisis when Mei gets lost.

Can humanity coexist harmoniously with the natural world?

'My Neighbor Totoro' presents an idealized vision of this coexistence. The Kusakabe family doesn't seek to control or exploit nature, but to live within it respectfully. Their awe and reverence for the camphor tree and the forest spirits stand in contrast to a modern, industrialized world that is often disconnected from its environment. The film posits that a spiritual connection to nature, one of friendship and respect, is not only possible but essential for human well-being and a touchstone for what is being lost.

Is a narrative required to have a villain or overt conflict to be compelling?

Miyazaki deliberately avoids a traditional narrative structure. There is no antagonist; the only 'conflict' is the family's internal struggle with anxiety and the brief, gentle crisis of Mei getting lost. The film's power comes from its atmosphere, its detailed depiction of ordinary life, and its moments of quiet wonder. It challenges the Western storytelling convention that a plot must be driven by external opposition, suggesting that a story can be just as compelling by focusing on character, emotion, and the beauty of small, magical moments.

Core Meaning

The core meaning of 'My Neighbor Totoro' lies in its exploration of the relationship between childhood innocence, the natural world, and the power of imagination as a means of coping with life's anxieties. Director Hayao Miyazaki conveys a profound respect for nature, rooted in Shinto beliefs, where spirits (kami) reside in all things, from ancient trees to tiny acorns. Totoro and the other spirits are not just fantastical creatures; they are the embodiment of the forest's life force, visible only to children whose hearts are open to wonder. The film suggests that this connection to nature provides spiritual nourishment and resilience, especially during difficult times. It is a gentle yet powerful statement on the importance of family bonds and how embracing the magical, unseen world can help navigate the very real fears and hardships of life.