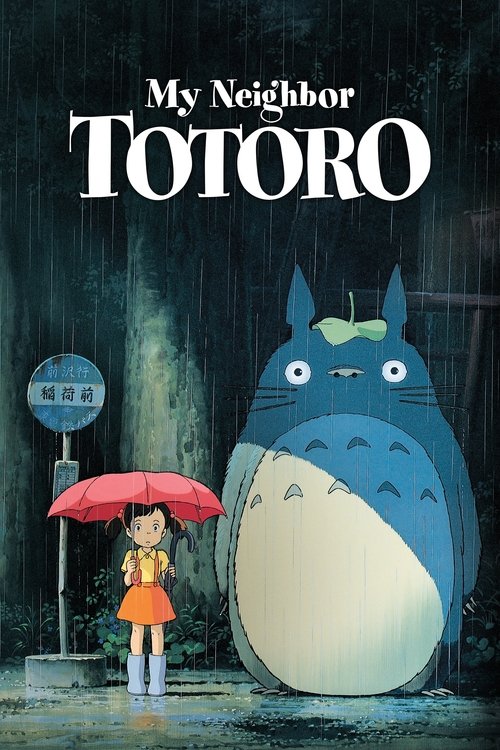

My Neighbor Totoro

となりのトトロ

"He's your friendly neighbourhood forest spirit!"

Overview

Set in 1950s rural Japan, 'My Neighbor Totoro' follows two young sisters, Satsuki and Mei, who move to an old countryside house with their father, Tatsuo, to be closer to their mother, Yasuko, who is recovering from a long-term illness in a nearby hospital. As they explore their new home and the vast, enchanting forest that surrounds it, the girls discover a world of gentle spirits.

The youngest, Mei, full of curiosity, wanders off and encounters magical creatures, including a giant, furry, sleepy forest spirit she names 'Totoro'. Initially, Satsuki is skeptical of her sister's tales, but she soon has her own encounters with these wondrous beings. The film eschews a traditional conflict-driven plot, instead focusing on the girls' episodic adventures with Totoro and his friends, including the grinning, multi-legged Catbus. These magical experiences run parallel to their daily lives and the underlying anxiety about their mother's health, offering them comfort and a sense of security.

Core Meaning

The core meaning of 'My Neighbor Totoro' lies in its exploration of the relationship between childhood innocence, the natural world, and the power of imagination as a means of coping with life's anxieties. Director Hayao Miyazaki conveys a profound respect for nature, rooted in Shinto beliefs, where spirits (kami) reside in all things, from ancient trees to tiny acorns. Totoro and the other spirits are not just fantastical creatures; they are the embodiment of the forest's life force, visible only to children whose hearts are open to wonder. The film suggests that this connection to nature provides spiritual nourishment and resilience, especially during difficult times. It is a gentle yet powerful statement on the importance of family bonds and how embracing the magical, unseen world can help navigate the very real fears and hardships of life.

Thematic DNA

The Wonder of Childhood and Imagination

The film is a celebration of childhood innocence and the boundless capacity of a child's imagination. Satsuki and Mei's ability to see and interact with the Totoros is a privilege of their youth. Their world is one where the mundane and the magical seamlessly blend; a forest path can lead to a spirit's lair, and a giant cat can be a bus. Miyazaki portrays this not as mere escapism, but as a valid and essential way of processing the world. Their father never dismisses their stories, fostering their imaginative spirit and suggesting that this way of seeing is a source of strength and joy.

Reverence for Nature and Environmentalism

At its heart, 'My Neighbor Totoro' is a love letter to the Japanese countryside and a manifestation of Shinto animism. The giant camphor tree where Totoro resides is treated as a sacred entity, with the family bowing to it in respect. Totoro himself is the guardian spirit of the forest, a physical representation of nature's power, mystery, and benevolence. The film was created during a period of rapid industrialization in Japan, and it serves as a nostalgic ode to a simpler, more harmonious relationship between humans and the environment, urging an appreciation for the natural world that is being lost.

Family Bonds and Resilience in Adversity

The underlying emotional core of the film is the Kusakabe family's quiet struggle with their mother's illness. The magical elements serve as a comforting force that helps the sisters cope with their fear and loneliness. The relationship between Satsuki and Mei is central; Satsuki takes on a motherly role, but her own fears and frustrations show the strain of her responsibilities. Their father's gentle guidance and their strong family unit, supported by the kindness of their neighbors like Granny, create a secure base from which they can face their worries. The film emphasizes that love and support are crucial for enduring hardship.

The Value of Rural and Community Life

The film idealizes rural life, presenting the countryside as a place of beauty, freedom, and community. The move from the city is transformative for the girls, allowing them to explore and connect with nature directly. The community is depicted as warm and supportive; neighbors like Granny and Kanta's family immediately help the Kusakabes, showcasing a sense of collective care that contrasts with urban anonymity. This portrayal reflects a nostalgia for a post-war era in Japan defined by strong communal ties and a simpler way of living.

Character Analysis

Satsuki Kusakabe

Noriko Hidaka

Motivation

Her primary motivation is to protect her younger sister, Mei, and to keep her family running smoothly while her mother is away. She feels a deep sense of responsibility to be strong for everyone, especially Mei.

Character Arc

Satsuki begins the film by embracing the move with enthusiasm, but she quickly assumes a parental role in her mother's absence, caring for Mei and managing household chores. Her arc involves navigating the difficult balance between being a responsible older sister and allowing herself to be a child. When she receives troubling news from the hospital, her maturity cracks, revealing the scared child underneath. Her journey culminates in her humbling herself to ask Totoro for help, fully embracing the world of childlike faith to solve a real-world crisis and reaffirming her bond with her sister.

Mei Kusakabe

Chika Sakamoto

Motivation

Mei is motivated by an insatiable curiosity about the world around her and a deep, simple love for her family. She wants to see her mother and believes a fresh ear of corn can make her well.

Character Arc

Mei, at four years old, is the embodiment of pure curiosity and innocence. Her arc is less about change and more about discovery. She is the first to bridge the gap between the human and spirit worlds through her fearless and open-hearted nature. Her journey through the film is one of constant wonder, from discovering soot sprites to tumbling into Totoro's lair. Her unwavering belief serves as the catalyst for the family's magical experiences. Her decision to walk to the hospital alone shows her deep love and a naive understanding of the world, leading to the film's gentle climax.

Tatsuo Kusakabe

Shigesato Itoi

Motivation

His motivation is to provide a safe, happy, and supportive environment for his daughters during the difficult period of their mother's illness. He strives to balance his work as a university professor with being a fully present and engaged father.

Character Arc

Tatsuo serves as the film's anchor of stability and warmth. He does not undergo a significant personal transformation but is crucial for enabling the girls' character arcs. He moves his family to the countryside and encourages his daughters' imaginations, never doubting their stories of forest spirits. His arc is one of consistent, gentle parenting, demonstrating how to face uncertainty with kindness, humor, and respect for both the spiritual and natural worlds. He represents an idealized father figure who validates his children's realities.

Totoro

Hitoshi Takagi

Motivation

As a spirit of the forest, Totoro's motivation is seemingly to maintain the natural order and, in his own quiet way, to watch over those who respect his domain. He helps the girls simply because they are good-hearted children who have shown him kindness and respect.

Character Arc

Totoro is a static character, a force of nature rather than an individual with a personal journey. He is ancient, powerful, and serene. His 'arc' is defined by his increasing interactions with the girls. He starts as a mysterious, sleeping giant and becomes their protector and magical friend. He doesn't change, but his presence facilitates change and growth in the human characters, providing comfort and miraculous assistance when they need it most.

Symbols & Motifs

Totoro

Totoro symbolizes the spirit of the forest, a benevolent guardian of nature who is both powerful and gentle. He represents a comforting and protective force for the children, appearing in moments of need or wonder. His existence embodies the magic and mystery of the natural world that is accessible only to the pure-hearted and innocent.

Mei is the first to discover Totoro sleeping in the hollow of a giant camphor tree. He later appears at the bus stop in the rain with Satsuki, shares a magical dance to make seeds sprout into a giant tree overnight, and ultimately summons the Catbus to help Satsuki find the lost Mei.

The Great Camphor Tree

The ancient camphor tree is a powerful symbol of nature's enduring presence and spirituality. In Shintoism, such large, old trees are considered sacred (shinboku), often adorned with a shimenawa rope to denote the presence of a deity. It represents a gateway between the human and spirit worlds, a source of life, and a symbol of stability and ancient wisdom.

The tree dominates the landscape near the girls' new house. It is where Totoro and the other spirits live. After Mei's first encounter, her father takes both daughters to the tree to pay their respects, telling them, 'Trees and people used to be good friends.' This act formalizes the family's respectful relationship with nature.

Catbus (Nekobasu)

The Catbus is a manifestation of pure, whimsical imagination. It represents a magical solution to earthly problems and the boundless possibilities when one believes in the fantastical. It symbolizes a bridge between places, between anxiety and relief, and between the human and spirit worlds, serving as a friendly and powerful ally.

The Catbus first appears to Satsuki and Mei at the bus stop, carrying Totoro. Later, when Mei is lost, a desperate Satsuki begs Totoro for help. He summons the Catbus, which enthusiastically whisks Satsuki across the countryside, its destination sign changing to 'MEI', to find her sister and then take them to the hospital to see their mother.

Soot Sprites (Susuwatari)

The Susuwatari, or 'wandering soot,' symbolize the initial fear of the unknown that comes with a new and unfamiliar place. They are shy, harmless creatures that inhabit empty spaces. Their departure signifies that the house has been filled with life and laughter, and that the family has made the new space their own, transforming fear into comfort.

Upon arriving at their new, dilapidated house, Satsuki and Mei discover swarms of these black, fuzzy creatures in the dark corners and attic. Granny explains they are harmless and will leave once they get used to the family's presence. Later, the family sees the soot sprites flying out of the house and towards the camphor tree, indicating their acceptance of the new residents.

Acorns

Acorns function as a currency of friendship and a symbol of potential and growth. They are the first sign of the spirits' presence and act as gifts from Totoro, initiating the bond between him and the children. They represent the seeds of magic and the promise of future wonders.

Mei first follows the trail of acorns left by the smaller Totoros, which leads her to the great camphor tree. Later, at the bus stop, Totoro gives the girls a small, magical bundle of nuts and seeds in return for sharing their umbrella. The girls plant these seeds, and Totoro later helps them magically grow into a giant tree for a single night.

Memorable Quotes

木と人間は、昔は仲が良かったんだ。 (Ki to ningen wa, mukashi wa naka ga yokatta n da.)

— Tatsuo Kusakabe

Context:

Spoken by the father to his daughters as they stand before the giant camphor tree. After Mei has told him about meeting Totoro, he brings them to the tree to offer a formal greeting, showing his respect for the spirits of the forest and validating Mei's experience.

Meaning:

Translated as, 'Trees and people used to be good friends.' This line encapsulates one of the film's central themes: the harmonious relationship between humanity and nature. It expresses a sense of nostalgia for a time when this connection was stronger and encourages the girls (and the audience) to view nature with respect and friendship.

みんな、笑ってみな。おっかないのが、逃げちゃうから。 (Minna, waratte mina. Okkanai no ga, nigechau kara.)

— Tatsuo Kusakabe

Context:

During a windy, stormy night, the old house rattles and shakes, frightening the girls. Their father, instead of dismissing their fears, encourages them to laugh loudly and heartily with him. Their collective laughter fills the house, overpowering the sound of the wind and turning a scary moment into a joyous one.

Meaning:

Translated as, 'Everybody, try laughing. Then whatever scares you will go away.' This quote offers the family's core philosophy for dealing with fear and uncertainty. It's a powerful and simple message that advocates for choosing joy and positivity as a coping mechanism, a lesson the girls apply when facing both supernatural 'spooks' and real-life anxieties.

トトロ、メイをお願い… (Totoro, Mei o onegai...)

— Satsuki Kusakabe

Context:

After searching desperately for her lost sister, Mei, and with the whole village unable to find her, a distraught Satsuki runs to the camphor tree. She tearfully begs Totoro for help, demonstrating her absolute faith in him as a guardian spirit.

Meaning:

Translated as, 'Totoro, please protect Mei...' followed by a plea for his help. This moment is the climax of Satsuki's emotional arc. After trying to be an adult for so long, she finally admits her fear and helplessness, placing her trust entirely in the magical world she has come to believe in. It signifies the complete fusion of the real and fantastical in her quest to save her sister.

夢だけど、夢じゃなかった! (Yume da kedo, yume ja nakatta!)

— Satsuki and Mei Kusakabe

Context:

The morning after Totoro, Satsuki, and Mei perform a magical ceremony to make the seeds they planted sprout into a gigantic tree, they wake up to find the great tree is gone. However, they discover that the seeds have indeed sprouted into small shoots overnight. They shout this line in joyous confusion, acknowledging the magical night they shared.

Meaning:

Translated as, 'It was a dream, but it wasn't a dream!' This line perfectly captures the film's ambiguous and beautiful approach to the magical events. It suggests that the experiences with Totoro exist in a space between reality and imagination, and that for the children, this distinction doesn't matter. The feeling and the impact of the experience are what is real and true.

Philosophical Questions

What is the relationship between imagination and reality, especially during hardship?

The film explores whether the magical events are 'real' or a product of the girls' imaginations as a coping mechanism for their mother's illness. Tatsuo, their father, treats their encounters as real, suggesting that the subjective reality of a child is as valid as an adult's objective one. The film doesn't provide a definitive answer, implying that the distinction is unimportant. The power of their belief, whether real or imagined, is what gives them the strength to endure their anxieties and ultimately leads to the resolution of their immediate crisis when Mei gets lost.

Can humanity coexist harmoniously with the natural world?

'My Neighbor Totoro' presents an idealized vision of this coexistence. The Kusakabe family doesn't seek to control or exploit nature, but to live within it respectfully. Their awe and reverence for the camphor tree and the forest spirits stand in contrast to a modern, industrialized world that is often disconnected from its environment. The film posits that a spiritual connection to nature, one of friendship and respect, is not only possible but essential for human well-being and a touchstone for what is being lost.

Is a narrative required to have a villain or overt conflict to be compelling?

Miyazaki deliberately avoids a traditional narrative structure. There is no antagonist; the only 'conflict' is the family's internal struggle with anxiety and the brief, gentle crisis of Mei getting lost. The film's power comes from its atmosphere, its detailed depiction of ordinary life, and its moments of quiet wonder. It challenges the Western storytelling convention that a plot must be driven by external opposition, suggesting that a story can be just as compelling by focusing on character, emotion, and the beauty of small, magical moments.

Alternative Interpretations

The most famous alternative interpretation of 'My Neighbor Totoro' is a dark fan theory suggesting that Totoro is a 'God of Death' (shinigami) and that the two sisters are actually dead or dying by the end of the film. Proponents of this theory point to several 'clues': the fact that the Catbus's destination sign changes to 'Mei' could be interpreted as her being a lost soul; a sandal found in a pond is initially thought to be Mei's, suggesting she drowned; and in the final scenes, the sisters appear to lack shadows. The theory often connects the story to the Sayama Incident, a real-life crime case involving the murder of two sisters.

However, Studio Ghibli has officially and emphatically debunked this theory. In a public statement, the studio confirmed that Totoro is not a God of Death and the girls are alive and well. They explained the lack of shadows in the final scene was a conscious artistic choice by the animation team, who decided that shadows were not stylistically necessary for that particular shot. The accepted and intended interpretation of the film is the one presented at face value: a heartwarming tale of children whose imaginative connection with benevolent nature spirits helps them through a difficult time.

Cultural Impact

The cultural impact of 'My Neighbor Totoro' is immense and enduring. Released in 1988, the film initially had a modest box office performance but gained phenomenal success through television reruns and home video, cementing Studio Ghibli's reputation. The titular character, Totoro, has become an international cultural icon, serving as the beloved mascot for Studio Ghibli itself. His image is ubiquitous in Japan and recognized globally as a symbol of Japanese animation. The film played a pivotal role in introducing international audiences to a gentler, more atmospheric style of storytelling in anime, moving beyond the action-oriented tropes often associated with the medium.

Its nostalgic depiction of the 1950s Japanese countryside resonated deeply within Japan, evoking a romanticized 'furusato' (hometown) that was disappearing due to rapid urbanization. The film's subtle integration of Shinto-animist beliefs, which revere nature as sacred and alive with spirits, presented a core aspect of Japanese culture to a global audience in an accessible and enchanting way. 'My Neighbor Totoro' has influenced countless animators and filmmakers worldwide with its focus on 'ma' (negative space or quiet pauses) and its ability to build a rich world without a conventional villain or high-stakes conflict. Its themes of environmentalism, family, and childhood wonder continue to be critically acclaimed and have made it a timeless classic for all ages.

Audience Reception

'My Neighbor Totoro' has received near-universal critical and audience acclaim since its release, and is widely regarded as one of the greatest animated films of all time. Audiences consistently praise its heartwarming story, breathtaking hand-drawn animation, and lovable characters, especially the iconic Totoro. It is celebrated for its ability to capture the authentic feeling of childhood innocence and wonder without resorting to melodrama or cynicism. The gentle pacing and lack of a central villain are often cited as major strengths, creating a serene and joyful viewing experience that appeals to both children and adults.

What little criticism exists is often directed at its unconventional, low-stakes plot, which some viewers accustomed to conflict-driven narratives might perceive as slow or uneventful. However, most fans and critics argue this is a deliberate and effective choice that defines the film's unique charm. The film's emotional depth, particularly in its subtle handling of the family's anxiety, is also frequently lauded. Overall, the verdict is that 'My Neighbor Totoro' is a timeless masterpiece of gentle storytelling and visual artistry.

Interesting Facts

- The film was initially considered a financial risk and was rejected by financiers; it was only greenlit when it was proposed as a double feature with the more 'prestigious' and tragic film, 'Grave of the Fireflies'.

- The story is semi-autobiographical. When Hayao Miyazaki was a child, his mother suffered from spinal tuberculosis for many years and was hospitalized, much like the mother in the film.

- The setting is inspired by the Sayama Hills area in Tokorozawa, where Miyazaki lives. The area is now popularly known as 'Totoro's Forest' and a conservation effort was started to protect it.

- The name 'Totoro' is Mei's mispronunciation of the Japanese word for 'troll' (torōru), which she would have seen in her storybooks.

- Originally, the story featured only one protagonist, a young girl who was a combination of both Satsuki and Mei. Miyazaki split her into two sisters to make the story more dynamic.

- The iconic Totoro has become the official mascot for Studio Ghibli and is one of the most recognizable characters in Japanese animation worldwide.

- A real-life replica of Satsuki and Mei's house was built for the 2005 World's Fair in Nagoya, Japan, and remains a popular tourist attraction.

- There is a 13-minute short film sequel called 'Mei and the Kittenbus', which is shown exclusively at the Ghibli Museum in Mitaka, Tokyo.

Easter Eggs

The Soot Sprites (Susuwatari) from 'My Neighbor Totoro' also appear in the 2001 Studio Ghibli film 'Spirited Away'.

In 'Spirited Away', these creatures work in the boiler room under the command of Kamaji. This shared element is a fun nod for Ghibli fans, creating a sense of a connected universe of magical beings imagined by Miyazaki.

In 'Kiki's Delivery Service' (1989), a model of a house on a bookshelf in Kiki's room features small figures of Mei and a mini Totoro in the windows.

This is a small, charming cameo that is easy to miss. It shows a cross-pollination of Ghibli's worlds and suggests that Kiki is familiar with the story of Totoro, placing the characters in a shared cultural (or perhaps literal) universe.

A stuffed Totoro toy makes a cameo appearance in Disney/Pixar's 'Toy Story 3' (2010).

This was an intentional tribute from Pixar's John Lasseter, a close friend of Hayao Miyazaki and a great admirer of his work. It demonstrates the immense respect for and cultural impact of 'My Neighbor Totoro' far beyond Japan.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!