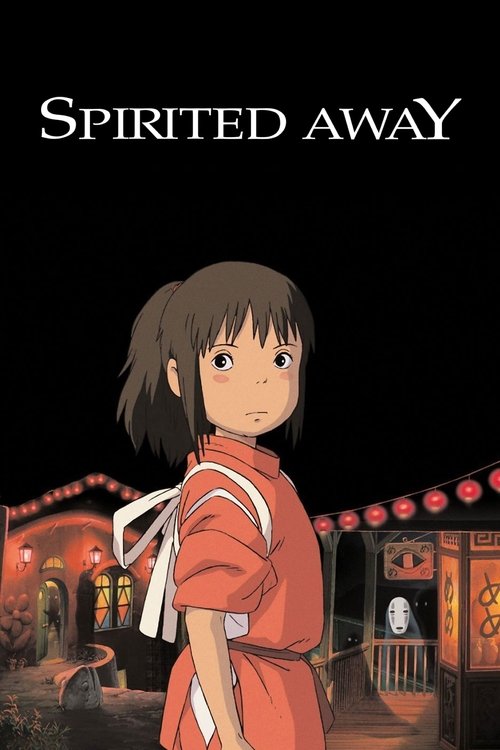

千と千尋の神隠し

Spirited Away - Symbolism & Philosophy

Symbols & Motifs

Names

Names symbolize identity and control. To lose one's name is to lose one's sense of self and past. Yubaba enslaves her workers by taking their names, binding them to the bathhouse. Chihiro must hold on to her real name to remember her mission and her connection to the human world. Haku has forgotten his name and is thus trapped in servitude. Chihiro remembering his true name, Kohaku River, frees him.

When Chihiro signs a work contract with Yubaba, the witch magically removes characters from her name (千尋) to rename her Sen (千). Haku repeatedly warns Sen not to forget her true name. The climax of Haku's arc occurs when Chihiro remembers he is the spirit of the Kohaku River, breaking Yubaba's control over him.

The Bathhouse (Aburaya)

The bathhouse is a microcosm of modern Japanese society, with its strict hierarchies, relentless labor, and focus on profit. It represents a world governed by rules and transactions, where value is determined by one's usefulness and ability to generate wealth. It's a place of purification for the spirits, but also a site of corruption and greed.

The entire middle section of the film takes place within the bathhouse. Its structure reflects its hierarchy, with the workers' quarters at the bottom and Yubaba's opulent penthouse at the very top. Chihiro's journey involves learning to navigate this complex social structure, from cleaning floors to serving the highest-ranking spirits.

Pigs

Pigs are a potent symbol of greed, gluttony, and the loss of humanity due to consumerism. Miyazaki stated that the transformation of Chihiro's parents was a metaphor for people during Japan's bubble economy who became greedy and never realized they had lost their humanity.

At the beginning of the film, Chihiro's parents gorge themselves on food meant for the spirits and are unceremoniously turned into pigs. They remain this way for most of the film. In the final test, Chihiro must identify her parents from a pen of pigs to break the spell.

No-Face (Kaonashi)

No-Face symbolizes loneliness and the search for identity in a consumerist society. He has no voice or personality of his own, instead reflecting the desires and emotions of those he encounters. In the bathhouse, surrounded by greed, he becomes a monstrous consumer, demanding attention by offering gold. He represents a personality shaped and corrupted by its environment.

No-Face first appears as a shy, translucent spirit whom Chihiro shows kindness to by letting him inside out of the rain. Inside the bathhouse, he observes the staff's obsession with gold and begins to magically produce it, growing larger and more aggressive as he consumes workers and food. He is only pacified when Chihiro feeds him a magic emetic cake and leads him away from the corrupting influence of the bathhouse.

The Train

The train journey represents a passage or transition, both literally and metaphorically. It is a journey into the unknown, a moment of quiet reflection and a departure from the chaotic world of the bathhouse. It symbolizes Chihiro's growth, as she embarks on a selfless mission not for herself, but to save Haku.

To return a stolen seal to Zeniba, Chihiro takes a one-way train that travels across a vast, shallow sea. The journey is quiet and contemplative, with shadowy, featureless figures as fellow passengers. This scene marks a significant shift in the film's tone and in Chihiro's personal development.

Philosophical Questions

What is the relationship between memory, name, and identity?

The film deeply explores the idea that one's identity is inextricably linked to one's name and past. Yubaba's control is predicated on stripping individuals of their names, thereby severing them from their history and sense of self. Haku is a powerful being, yet he is completely subservient because he cannot remember who he is. The film posits that true freedom is impossible without self-knowledge, which is rooted in memory. Chihiro's journey is not just about survival, but about actively holding onto her identity, and in doing so, she is able to liberate others by helping them remember theirs.

How does an environment shape an individual's morality and behavior?

"Spirited Away" uses the character of No-Face to powerfully illustrate this question. He arrives as a blank slate, a quiet and seemingly harmless spirit. However, when he enters the bathhouse, an environment driven by greed and transactional relationships, he learns to behave in the only way that gets him attention: by offering gold and consuming everything in his path. He becomes a monster. It is only when Chihiro removes him from this toxic environment and brings him to Zeniba's simple, nurturing home that he can return to a gentle, calm state. The film suggests that morality is not always inherent but can be profoundly influenced by the values of the society one is immersed in.

Can one mature without losing the core of one's childhood self?

The film charts Chihiro's significant growth from a frightened child to a capable young woman. She learns to work hard, be responsible, and confront her fears. Yet, the very qualities that allow her to succeed are rooted in her childlike nature: her innate kindness, her lack of greed, and her capacity for empathy. She shows compassion to the Stink Spirit, Haku, and No-Face when others will not. The film suggests that true maturity is not the abandonment of childhood virtues but the integration of them with newfound strength and wisdom. Chihiro becomes more capable without becoming cynical.

Core Meaning

The core meaning of "Spirited Away" revolves around Chihiro's journey from a state of childish apathy to one of responsibility, courage, and self-awareness. Director Hayao Miyazaki intended the film to be a story for ten-year-old girls, creating a heroine they could look up to who isn't a traditional hero but an ordinary girl who finds her strength through perseverance.

The film serves as a powerful allegory for the challenges of navigating the adult world and the importance of holding onto one's identity in the face of societal pressures that seek to commodify and control. It critiques modern greed and consumerism, symbolized by Chihiro's parents turning into pigs, reflecting Japan's bubble economy of the 1980s. Ultimately, it is a story about adaptation, the pain and beauty of change, and the idea that love, hard work, and maintaining one's inner self are the keys to overcoming adversity.