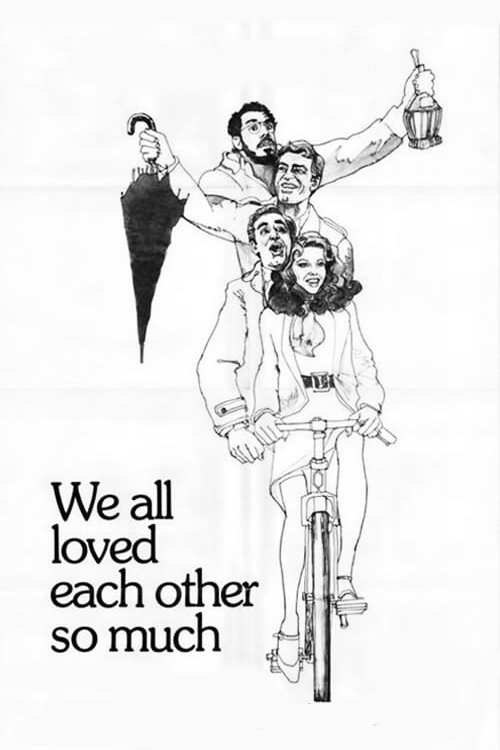

C'eravamo tanto amati

"A many splendored thing."

We All Loved Each Other So Much - Symbolism & Philosophy

Symbols & Motifs

Italian Cinema (Neorealism, Fellini)

Symbolizes the ideals, dreams, and eventual disillusionment of the post-war generation. Neorealist films like "Bicycle Thieves" represent the raw, hopeful, and politically committed spirit of the era, which Nicola champions. Later, references to Fellini's "La Dolce Vita" signify the shift towards an era of economic boom, glamour, and moral ambiguity.

Nicola loses his teaching job for his passionate defense of "Bicycle Thieves." The friends' lives intersect with the film world, most notably when Antonio finds Luciana working as an extra on the set of "La Dolce Vita" at the Trevi Fountain, featuring cameos by Fellini and Mastroianni. The film is explicitly dedicated to Vittorio De Sica.

The Restaurant ("Re della mezza porzione")

Represents the central meeting point and emotional battleground for the friends. It is a space of communion, conflict, love, and heartbreak, symbolizing the recurring intersections of their lives despite their diverging paths.

The restaurant is where Antonio and Luciana have their first dates, where Gianni and Luciana fall for each other, and where the three friends have a pivotal, confrontational reunion dinner years later that ends in a brawl.

Gianni's Villa

Symbolizes the corrupting influence of wealth and the ultimate abandonment of the friends' shared youthful ideals. It stands in stark contrast to the humble beginnings and leftist principles they once shared, representing Gianni's moral and political capitulation.

The film opens and closes with Antonio, Nicola, and Luciana outside the gates of Gianni's luxurious villa, realizing the immense gap that has grown between them. They see he has become wealthy and successful but has lied about his circumstances, choosing his new life over his old friendships.

The Diverging Paths

The different professions and social statuses of the three men symbolize the fragmentation of post-war Italian society and the different ways individuals responded to the era's challenges. It's an allegory for the failure of a unified, leftist dream for Italy.

Gianni becomes a rich, morally compromised lawyer who marries into wealth. Antonio remains a working-class hospital orderly, principled but powerless. Nicola pursues an intellectual life as a film critic but is ultimately a failure, unable to compromise his rigid ideals.

Philosophical Questions

Can youthful ideals survive the compromises of adult life?

The film explores this question through the three divergent life paths of its protagonists. Gianni actively betrays his ideals for wealth and success, finding himself materially rich but emotionally and morally bankrupt. Nicola clings to his ideals so rigidly that he fails to adapt, leading to a life of poverty and bitterness. Antonio manages to retain his core principles but at the cost of ambition, living a simple but unfulfilled life. The film suggests that while the complete preservation of youthful idealism is nearly impossible, the cost of abandoning it entirely is a profound sense of loss and self-betrayal.

How do personal choices and historical forces interact to shape a life?

Scola masterfully intertwines the personal stories of the characters with the sweeping history of post-war Italy. The characters are not just individuals; they are products of their time, their decisions influenced by the political climate, the economic boom, and the cultural shifts occurring around them. Gianni's success is tied to the rise of speculative real estate development, while Nicola's struggles reflect the intellectual's marginalization in a consumerist society. The film suggests that while individuals make choices, their lives are ultimately steered and defined by the broader currents of history.

What is the role of memory in shaping our present?

The film's non-linear structure constantly juxtaposes past and present, highlighting how memory informs the characters' identities and relationships. Their shared memories of the Resistance are a source of unity but also a painful reminder of how far they have drifted. The narrative itself is an act of collective remembering, piecing together three decades of joy and disappointment. It suggests that we are in a constant dialogue with our past selves, and that the present is inescapably haunted by the ghosts of past hopes and failures.

Core Meaning

The central message of "We All Loved Each Other So Much" is a melancholic reflection on the erosion of youthful ideals and the inevitable compromises of life. Director Ettore Scola explores the disillusionment of a generation that fought for a better world during the Resistance, only to see their revolutionary hopes dissolve into consumerism, political instability, and personal ambition in post-war Italy. The film posits the question of whether it's possible to remain true to one's principles in a world that is constantly changing.

Through the divergent paths of its three protagonists, the film serves as an allegory for the broader social and political shifts in Italy over three decades. It contrasts the collectivist spirit of the past with the individualism of the present. Furthermore, the film is a profound homage to Italian cinema itself, suggesting that film is inextricably linked to the nation's history and collective memory, shaping and reflecting its identity. Ultimately, the film carries a sense of loss—not just of personal friendships, but of a shared national dream.