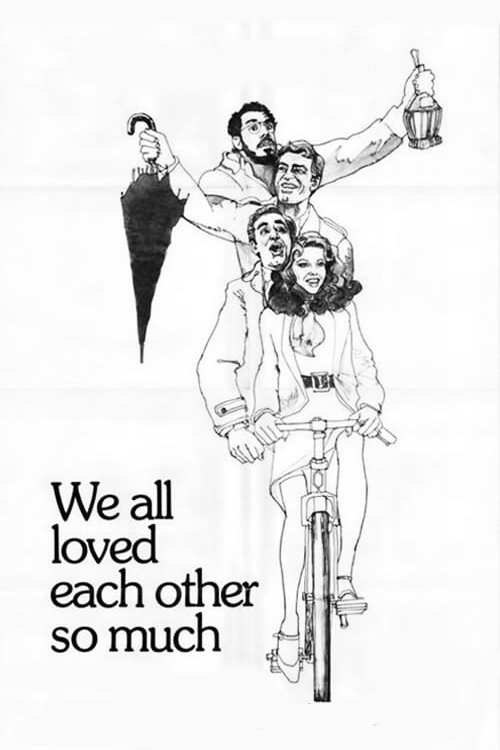

We All Loved Each Other So Much

C'eravamo tanto amati

"A many splendored thing."

Overview

"We All Loved Each Other So Much" ("C'eravamo tanto amati") chronicles the lives of three friends—Gianni, Antonio, and Nicola—over thirty years, from their shared experiences as partisans in World War II to the mid-1970s. United by their idealistic hopes for a new Italy, their paths diverge dramatically after the war. Antonio becomes a humble hospital orderly, Gianni a pragmatic and ambitious lawyer, and Nicola a passionate but unsuccessful intellectual and film critic.

Their lives are further complicated by their shared love for Luciana, a beautiful aspiring actress who becomes entangled with each of them at different times, acting as a catalyst that exposes their changing values and the fractures in their bond. The film charts their personal and professional successes and failures, their loves and betrayals, set against the backdrop of Italy's tumultuous post-war social, political, and economic transformation.

Through a non-linear narrative that jumps between different time periods and employs various cinematic techniques, director Ettore Scola creates a poignant and often humorous portrait of a generation's journey from collective hope to individual disillusionment. The film is a sprawling, melancholic, and deeply human story about the compromises of life, the passage of time, and the enduring, if complicated, nature of friendship.

Core Meaning

The central message of "We All Loved Each Other So Much" is a melancholic reflection on the erosion of youthful ideals and the inevitable compromises of life. Director Ettore Scola explores the disillusionment of a generation that fought for a better world during the Resistance, only to see their revolutionary hopes dissolve into consumerism, political instability, and personal ambition in post-war Italy. The film posits the question of whether it's possible to remain true to one's principles in a world that is constantly changing.

Through the divergent paths of its three protagonists, the film serves as an allegory for the broader social and political shifts in Italy over three decades. It contrasts the collectivist spirit of the past with the individualism of the present. Furthermore, the film is a profound homage to Italian cinema itself, suggesting that film is inextricably linked to the nation's history and collective memory, shaping and reflecting its identity. Ultimately, the film carries a sense of loss—not just of personal friendships, but of a shared national dream.

Thematic DNA

Disillusionment and Lost Ideals

The film's primary theme is the gradual fading of the idealistic fervor that united the three friends during the war. Their shared dream of building a more just society gives way to the harsh realities of post-war life. Gianni's ambition leads him to abandon his leftist principles for wealth and status. Nicola, who clings stubbornly to his ideals, finds himself marginalized and professionally thwarted. Antonio remains a man of the people but is consigned to a life of mediocrity. Their journey reflects a broader national sentiment of disillusionment as the promises of the Resistance failed to fully materialize amidst Italy's economic boom and political shifts.

Friendship and Betrayal

The enduring yet fragile bond between Gianni, Antonio, and Nicola is the emotional core of the film. Forged in the crucible of war, their friendship is tested by love, class differences, and ideological divergence. The love triangle involving Luciana creates the initial and most significant rift. Over the years, their meetings are tinged with resentment, nostalgia, and unspoken disappointments. Gianni's concealment of his wealth from his friends in the final act represents the ultimate betrayal, a symbol of how far he has drifted from their shared past and values.

The Passage of Time and Memory

Scola masterfully manipulates time, using a non-linear structure with flashbacks and flash-forwards to emphasize the theme of memory and the relentless passage of time. The narrative spans thirty years, showing how characters and the nation itself are transformed. The film often reflects on the past with a sense of bittersweet nostalgia, questioning the accuracy and comfort of memory. The opening and closing scenes, which frame the entire story, highlight the gap between past hopes and present realities, creating a poignant sense of cyclical disappointment.

Cinema as a Reflection of Life

The film is a self-reflexive love letter to Italian cinema, using it as a lens through which to view Italian history. Nicola's passion for film, particularly Neorealism, underscores the belief in cinema as a tool for social change. The narrative is peppered with homages to and cameos by figures like Vittorio De Sica, Federico Fellini, and Marcello Mastroianni. Scola even mimics different cinematic styles, shooting early scenes in black-and-white to evoke Neorealism and later scenes in color with a more lavish feel, mirroring the evolution of both the characters' lives and Italian film history.

Character Analysis

Gianni Perego

Vittorio Gassman

Motivation

Driven by a deep-seated ambition for success, wealth, and social status, even at the cost of his personal relationships and political ideals.

Character Arc

Gianni begins as an idealistic law student and partisan fighter. Post-war, his ambition leads him down a path of moral compromise. He leaves Luciana for a strategic marriage to Elide, the daughter of a corrupt construction magnate, ensuring his wealth and success. He abandons his socialist principles, becoming a successful but cynical and lonely man, ultimately alienated from his old friends and his former self.

Antonio

Nino Manfredi

Motivation

To live a simple, decent life, maintain his friendships, and find love and stability. He is motivated by a fundamental sense of loyalty and a good heart.

Character Arc

Antonio is the most grounded and consistently principled of the group. He starts as a hospital orderly and remains one throughout his life, representing the steadfast, working-class conscience of the trio. He experiences heartbreak and disappointment, particularly in his unrequited love for Luciana, but finds a measure of contentment in a simple life with his family. He remains true to his leftist ideals, though he is less vocal and intellectual about them than Nicola.

Nicola Palumbo

Stefano Satta Flores

Motivation

A passionate and uncompromising belief in his political and cultural ideals, particularly the power of cinema to reflect truth and enact social change.

Character Arc

Nicola is a passionate, intellectual idealist, and a fervent cinephile. His refusal to compromise his rigid political and artistic beliefs leads to professional and personal failure. He loses his teaching job over an argument about the film "Bicycle Thieves," leaves his family, and moves to Rome to become a critic, only to struggle in poverty. He represents the tragedy of uncompromising idealism in a world that rewards pragmatism, becoming a bitter and disillusioned dreamer.

Luciana Zanon

Stefania Sandrelli

Motivation

Initially driven by the dream of becoming a successful actress, she is ultimately seeking love, stability, and a sense of belonging.

Character Arc

Luciana is the woman who all three men love at various points. An aspiring actress, she is a symbol of their shared desires and the object over which their friendship fractures. Her own life is one of struggle and disappointment; her dreams of stardom never materialize. She moves from a relationship with Antonio to a passionate affair with Gianni, and is later cared for by Nicola. Ultimately, she finds a quiet life with Antonio, representing a retreat from grand ambitions to simple, reliable affection.

Symbols & Motifs

Italian Cinema (Neorealism, Fellini)

Symbolizes the ideals, dreams, and eventual disillusionment of the post-war generation. Neorealist films like "Bicycle Thieves" represent the raw, hopeful, and politically committed spirit of the era, which Nicola champions. Later, references to Fellini's "La Dolce Vita" signify the shift towards an era of economic boom, glamour, and moral ambiguity.

Nicola loses his teaching job for his passionate defense of "Bicycle Thieves." The friends' lives intersect with the film world, most notably when Antonio finds Luciana working as an extra on the set of "La Dolce Vita" at the Trevi Fountain, featuring cameos by Fellini and Mastroianni. The film is explicitly dedicated to Vittorio De Sica.

The Restaurant ("Re della mezza porzione")

Represents the central meeting point and emotional battleground for the friends. It is a space of communion, conflict, love, and heartbreak, symbolizing the recurring intersections of their lives despite their diverging paths.

The restaurant is where Antonio and Luciana have their first dates, where Gianni and Luciana fall for each other, and where the three friends have a pivotal, confrontational reunion dinner years later that ends in a brawl.

Gianni's Villa

Symbolizes the corrupting influence of wealth and the ultimate abandonment of the friends' shared youthful ideals. It stands in stark contrast to the humble beginnings and leftist principles they once shared, representing Gianni's moral and political capitulation.

The film opens and closes with Antonio, Nicola, and Luciana outside the gates of Gianni's luxurious villa, realizing the immense gap that has grown between them. They see he has become wealthy and successful but has lied about his circumstances, choosing his new life over his old friendships.

The Diverging Paths

The different professions and social statuses of the three men symbolize the fragmentation of post-war Italian society and the different ways individuals responded to the era's challenges. It's an allegory for the failure of a unified, leftist dream for Italy.

Gianni becomes a rich, morally compromised lawyer who marries into wealth. Antonio remains a working-class hospital orderly, principled but powerless. Nicola pursues an intellectual life as a film critic but is ultimately a failure, unable to compromise his rigid ideals.

Memorable Quotes

Volevamo cambiare il mondo, ma il mondo ha cambiato noi.

— Gianni Perego

Context:

This is a sentiment expressed by Gianni, reflecting on the failure of their generation to achieve the societal transformation they fought for as partisans. It highlights the gap between their hopeful past and their compromised present.

Meaning:

"We wanted to change the world, but the world changed us." This line encapsulates the film's central theme of disillusionment. It's a bitter acknowledgment that the revolutionary ideals of their youth have been eroded by the compromises and realities of adult life and a changing society.

Credevamo di cambiare chissà che e invece... eccoci qua.

— Narrator / The Friends

Context:

This reflection occurs as the friends look back on their lives, underscoring the melancholy tone of the film and the common feeling of disappointment that unites them despite their different paths.

Meaning:

"We thought we were changing who knows what and instead... here we are." This quote echoes the theme of failed ambitions and the mundane reality that followed their heroic youth. It speaks to a sense of stagnation and the realization that their grand efforts did not lead to the grand results they expected.

Philosophical Questions

Can youthful ideals survive the compromises of adult life?

The film explores this question through the three divergent life paths of its protagonists. Gianni actively betrays his ideals for wealth and success, finding himself materially rich but emotionally and morally bankrupt. Nicola clings to his ideals so rigidly that he fails to adapt, leading to a life of poverty and bitterness. Antonio manages to retain his core principles but at the cost of ambition, living a simple but unfulfilled life. The film suggests that while the complete preservation of youthful idealism is nearly impossible, the cost of abandoning it entirely is a profound sense of loss and self-betrayal.

How do personal choices and historical forces interact to shape a life?

Scola masterfully intertwines the personal stories of the characters with the sweeping history of post-war Italy. The characters are not just individuals; they are products of their time, their decisions influenced by the political climate, the economic boom, and the cultural shifts occurring around them. Gianni's success is tied to the rise of speculative real estate development, while Nicola's struggles reflect the intellectual's marginalization in a consumerist society. The film suggests that while individuals make choices, their lives are ultimately steered and defined by the broader currents of history.

What is the role of memory in shaping our present?

The film's non-linear structure constantly juxtaposes past and present, highlighting how memory informs the characters' identities and relationships. Their shared memories of the Resistance are a source of unity but also a painful reminder of how far they have drifted. The narrative itself is an act of collective remembering, piecing together three decades of joy and disappointment. It suggests that we are in a constant dialogue with our past selves, and that the present is inescapably haunted by the ghosts of past hopes and failures.

Alternative Interpretations

While the dominant interpretation of the film is one of bittersweet melancholy over lost ideals, some alternative readings exist. One perspective is that the film is not just a lament but also a harsh critique of the Left's failure. Nicola, the intellectual, is portrayed as ineffectual, lost in the romance of cinema rather than engaging in tangible political action. Gianni's betrayal is not just a personal failing but represents the Left's seduction by capitalism. From this viewpoint, the film is less about nostalgia and more a satirical indictment of a generation's inability to translate its ideals into lasting change.

Another interpretation focuses more on the personal than the political. The film can be seen as a universal story about the nature of friendship and the inevitable changes wrought by time, ambition, and love, with the political backdrop serving more as a setting than the central message. It's a deeply human drama about how three distinct personalities react differently to the challenges of life, and how their bond, despite everything, never completely vanishes. The ending, where Gianni watches his friends from afar, can be read not just as a moment of alienation, but also as one of profound, enduring regret and a flicker of the love that still remains, however distant.

Cultural Impact

"We All Loved Each Other So Much" is regarded as a masterpiece of Italian cinema and a seminal work of the Commedia all'italiana genre. Released in 1974, it captured a specific moment of Italian reflection, looking back at the thirty years since the end of WWII with a mixture of nostalgia, humor, and profound melancholy. It chronicled the journey of a generation from the collective hope of the Resistance to the fragmented, consumerist society of the 1970s, resonating deeply with an audience grappling with political turmoil and social change.

The film's influence on cinema is significant for its complex, non-linear narrative and its self-reflexive engagement with film history. By embedding the story of Italian cinema within its own plot—paying direct homage to De Sica, Fellini, Rossellini, and Antonioni—Scola created a powerful statement on the role of art in shaping national identity. This metafictional approach, blending comedy with sharp social and political commentary, influenced subsequent generations of filmmakers.

Critically acclaimed upon its release, it won numerous international awards and cemented Ettore Scola's reputation as one of Italy's master directors. Its inclusion on the list of "100 Italian films to be saved" confirms its status as a work that has shaped the "collective memory of the country." The film's title itself has entered the Italian lexicon as a shorthand for expressing a bittersweet nostalgia for a past full of shared hopes that were never quite realized.

Audience Reception

Audiences have generally embraced "We All Loved Each Other So Much" as a poignant and masterful piece of Italian cinema. It is widely praised for its intelligent and moving script, its blend of laugh-out-loud comedy with deep pathos, and the stellar performances of its ensemble cast, particularly Vittorio Gassman, Nino Manfredi, and Stefania Sandrelli. Viewers often connect deeply with the universal themes of friendship, lost love, and the disillusionment that comes with age. The film's nostalgic and bittersweet tone resonates with many, who see it as an honest reflection on the compromises of life.

The main points of criticism, though few, sometimes center on its sprawling, episodic structure, which some viewers find can feel unfocused or drawn out. A few critics have noted that the film's deep immersion in Italian political and cinematic history might make some of its nuances less accessible to international audiences unfamiliar with the specific context. However, the overall verdict is overwhelmingly positive, with the film being celebrated as a wise, funny, and profoundly human epic that captures the soul of a generation and a nation.

Interesting Facts

- The film is dedicated to the great Italian director Vittorio De Sica, who passed away during its production. De Sica himself appears in the film in archival footage discussing his masterpiece, "Bicycle Thieves."

- The film features cameo appearances by iconic figures of Italian cinema, Federico Fellini and Marcello Mastroianni, who play themselves during a recreation of the filming of the Trevi Fountain scene from "La Dolce Vita".

- The screenplay was co-written by Ettore Scola with the legendary screenwriting duo Age & Scarpelli, known for many classics of the Commedia all'italiana genre.

- To reflect the different eras, Scola shot the first part of the film, set in the immediate post-war years, in black and white to evoke the style of Italian Neorealism, before transitioning to color as the story moves into the era of Italy's economic boom.

- In 2008, "We All Loved Each Other So Much" was included in the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage's list of "100 Italian films to be saved," a collection of films that are considered to have changed the country's collective memory between 1942 and 1978.

- The film won several prestigious awards, including the César Award for Best Foreign Film in 1977 and the Golden Prize at the 9th Moscow International Film Festival in 1975.

- Actors Vittorio Gassman and Nino Manfredi were known to have improvised some of their scenes, contributing to the naturalistic flow of the dialogue.

Easter Eggs

Homage to Vittorio De Sica's "Bicycle Thieves"

This is more than a simple reference; it's a central plot device. Nicola's life is ruined when he loses his job for passionately defending the film against detractors who saw it as presenting a poor image of Italy. Later, he loses a TV quiz show by giving a nuanced, intellectual answer about the film that the judges deem incorrect. The film's dedication to De Sica makes this recurring motif a profound tribute to the master of Neorealism.

Recreation of "La Dolce Vita" Trevi Fountain Scene

The film reconstructs the set of Fellini's iconic film, with Fellini and Mastroianni appearing as themselves. This scene serves multiple purposes: it grounds the film in a specific moment of Italian cultural history, it provides a backdrop for Antonio and Luciana's reunion, and it acts as a meta-commentary on the power and allure of cinema, contrasting the glamorous world of film with the characters' more mundane lives.

Use of Eugene O'Neill's "Strange Interlude" Theatrical Device

Early in the film, Antonio and Luciana see O'Neill's play, which is famous for its use of soliloquies where characters speak their inner thoughts directly to the audience. Scola then adopts this technique, having his own characters freeze the action and break the fourth wall to address the camera, revealing their true feelings and motivations. This stylistic choice creates a direct, intimate connection with the viewer and enhances the film's playful, self-aware tone.

Aldo Fabrizi's Casting

Aldo Fabrizi, who plays the corrupt, boorish construction magnate Romolo Catenacci, was famous for his heroic role as the Resistance priest in Roberto Rossellini's Neorealist masterpiece "Open City" (1945). His casting here as a symbol of post-war corruption and greed is a powerful, ironic commentary on how the ideals of the Resistance era were betrayed by subsequent generations.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!