City Lights

"True Blind Love"

Overview

"City Lights" is a poignant silent film that masterfully blends comedy, romance, and drama. The story follows the misadventures of Charlie Chaplin's iconic character, The Tramp, as he navigates the bustling, indifferent city. He falls deeply in love with a beautiful but blind flower girl and, through a misunderstanding, she believes him to be a wealthy duke.

Determined to help her, The Tramp embarks on a series of hilarious and often humiliating endeavors to earn money for an operation that could restore her sight. His life becomes further complicated by a turbulent friendship with a suicidal, eccentric millionaire who only recognizes him when drunk. The Tramp's unwavering devotion and selfless sacrifices form the emotional core of the film, as he strives to maintain the illusion of his wealth for the woman he loves.

Core Meaning

The core meaning of "City Lights" revolves around the idea that true sight is not physical but emotional and spiritual. The film posits that love and compassion transcend social class, appearances, and even physical senses. Director Charlie Chaplin wanted to convey a message about the enduring power of human decency and sacrifice in a world often characterized by indifference and materialism. The central message is that the greatest acts of love are often unseen and unrewarded, yet they hold the power to transform lives in the most profound ways. The film champions the purity of the heart over the illusions of wealth and status.

Thematic DNA

Love and Sacrifice

This is the central theme of the film, embodied by The Tramp's selfless devotion to the blind flower girl. He endures immense hardship, public humiliation, and even imprisonment, all to provide her with a chance to see again. His love is unconditional, and his sacrifices are made without any expectation of reward, highlighting the purity and depth of his affection. He is willing to risk losing her once she can see him for who he truly is, demonstrating the ultimate act of selfless love.

Class Disparity and Social Injustice

"City Lights" starkly contrasts the lives of the wealthy and the impoverished. The Tramp, representing the lowest rung of society, is consistently mistreated and overlooked. The Eccentric Millionaire, on the other hand, lives a life of careless luxury. The film critiques a society where a person's worth is judged by their wealth and status rather than their character. The millionaire's Jekyll-and-Hyde behavior—friendly when drunk and dismissive when sober—symbolizes the fickle and superficial nature of the upper class.

Perception vs. Reality (Blindness and Sight)

The theme is explored both literally and metaphorically. The flower girl is physically blind but can perceive The Tramp's inner kindness. Conversely, the millionaire is only able to "see" The Tramp's true friendship when his senses are clouded by alcohol. The film suggests that those with physical sight are often blind to what truly matters. The poignant final scene challenges the audience to consider what it means to truly see someone, culminating in the girl's recognition of her benefactor not by sight, but by touch and innate goodness.

Resilience and Hope

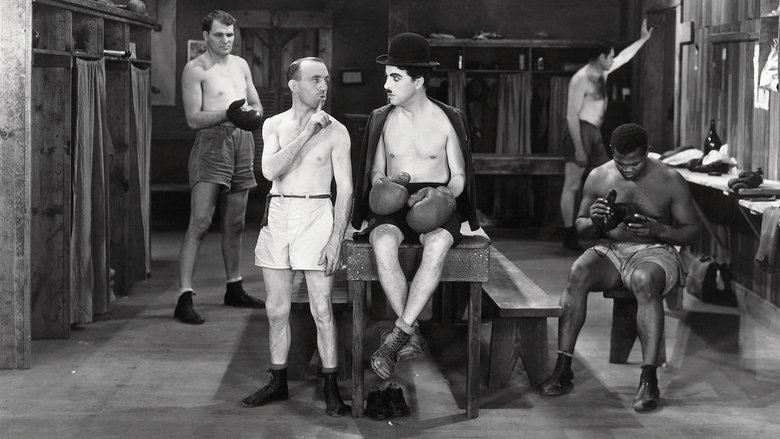

Despite constant adversity, The Tramp never loses his essential optimism and resilience. He faces each challenge—from street-sweeping to a rigged boxing match—with a blend of clumsiness and determination. His character embodies the persistence of the human spirit in the face of suffering and social rejection. His unwavering hope to help the flower girl fuels the narrative and provides a powerful message about finding purpose and dignity through acts of kindness.

Character Analysis

The Tramp

Charlie Chaplin

Motivation

His primary motivation is his pure, unconditional love for the blind flower girl. He is driven by the desire to help her, specifically to pay for the surgery that will restore her sight, even if it means she will then see him for the penniless tramp he is.

Character Arc

The Tramp begins as a solitary, aimless figure, an outsider simply trying to survive. His chance encounter with the blind flower girl gives his life purpose and direction. He transforms from a mere survivor into a selfless benefactor, undertaking immense personal sacrifices for her well-being. By the end, although he remains poor and is now even more downtrodden after his time in prison, he has achieved a profound moral victory. His final, heart-wrenching glance reveals a mixture of fear and hope, having found a connection that transcends his social status.

A Blind Girl

Virginia Cherrill

Motivation

Initially, her motivation is survival—to earn enough money to live and pay rent. Later, after her sight is restored, her motivation becomes finding and thanking the wealthy man she believes was her benefactor.

Character Arc

The Blind Girl starts as a poor, vulnerable, and dependent character, selling flowers to support herself and her grandmother. Through The Tramp's secret generosity, she gains her sight and economic independence, opening her own successful flower shop. Her arc culminates in the final scene where her physical sight is matched by a deeper, emotional recognition of her true benefactor. She moves from a state of idealized, mistaken love for a rich man to a genuine, compassionate understanding of the poor man who sacrificed everything for her.

An Eccentric Millionaire

Harry Myers

Motivation

His motivations are erratic and driven by his state of intoxication. When drunk, he seeks friendship and excitement, viewing The Tramp as his savior and companion. When sober, he is motivated by the conventions of his social class, which dictate that he should have nothing to do with a tramp.

Character Arc

The Millionaire does not have a traditional character arc; rather, he exists in a cyclical state. He repeatedly swings between two personas: a generous, life-loving best friend to The Tramp when intoxicated, and a cold, dismissive stranger when sober. His character serves as a plot device, providing The Tramp with the means to help the girl, but also as a symbol of the superficiality and unreliability of the upper class. He never reconciles his two halves, remaining a tragicomic figure trapped by his alcoholism and social standing.

Symbols & Motifs

Flowers

The flowers symbolize purity, beauty, love, and the fragile connection between The Tramp and the girl. They represent the simple, natural beauty that stands in contrast to the cold, indifferent city.

The Tramp first meets the girl when he buys a flower from her. He cherishes the flower she gives him, carrying it with him as a symbol of his love. At the end, it is through her act of giving him a flower that she finally recognizes him.

Blindness

Blindness in the film is a metaphor for the inability to see the true nature of people and situations. While the flower girl is literally blind, other characters are metaphorically blind to qualities like kindness and integrity.

The flower girl cannot see that The Tramp is poor. The millionaire is "blind" to his friendship with The Tramp when he is sober. The film suggests that true vision comes from the heart, not the eyes.

The Statue of 'Peace and Prosperity'

The monument unveiled at the beginning of the film symbolizes the hypocrisy and hollowness of civic pride and the indifference of society towards the poor.

The film opens with the unveiling of this grand statue, only to reveal The Tramp sleeping in its lap. This immediately establishes him as an outcast and satirizes the empty promises of a society that erects monuments to prosperity while ignoring the poverty at its feet. The squawking, kazoo-like voices of the dignitaries further mock the empty rhetoric of those in power.

The Tramp's Cane

The cane represents The Tramp's resilience and his clumsy but determined attempts to navigate a hostile world. It's a tool for both physical comedy and a symbol of his enduring, if awkward, dignity.

The Tramp uses his cane throughout the film in various slapstick routines, such as when he gets it caught in a grate or fends off newsboys. It's an extension of his character—unrefined but surprisingly effective in getting him through scrapes.

Memorable Quotes

Yes, I can see now.

— A Blind Girl

Context:

The girl, her sight restored, has opened a flower shop. She takes pity on a shabby tramp outside, offering him a flower and a coin. When their hands touch, she recognizes him as her benefactor. He asks, via intertitle, "You can see now?" and she responds with this line, her eyes filled with a mix of pity, gratitude, and dawning love.

Meaning:

This is the film's climactic line, delivered in the final, emotionally charged scene. Its significance is twofold: she can literally see for the first time, but more profoundly, she now 'sees' the truth of The Tramp's identity and the depth of his love and sacrifice. It represents the film's core theme of true sight being an emotional, not physical, perception.

Tomorrow the birds will sing.

— The Tramp

Context:

The Tramp says this to the Eccentric Millionaire after stopping him from attempting suicide. It is his gentle, philosophical way of convincing the despondent man that life is still worth living.

Meaning:

This quote encapsulates The Tramp's unwavering optimism and his role as a source of hope, even in the face of despair. He offers this simple, poetic encouragement to the millionaire, reminding him that no matter how dark things seem, there is always the promise of a new day and simple beauty in the world.

Am I driving?

— An Eccentric Millionaire

Context:

The Tramp is in the passenger seat, terrified, as the millionaire erratically speeds through the city streets. After The Tramp nervously tells him, "Be careful how you're driving," the millionaire responds with this blissfully unaware question.

Meaning:

This line provides a moment of pure slapstick comedy and highlights the millionaire's complete obliviousness due to his drunkenness. It underscores the chaotic and dangerous nature of his friendship with The Tramp, while also being hilariously absurd.

Philosophical Questions

What is the nature of true sight and perception?

The film delves into this question by contrasting literal sight with emotional and moral insight. The Blind Girl cannot see The Tramp's poverty and instead perceives his inner kindness. The Eccentric Millionaire can only recognize his friend when his perception is altered by alcohol. Chaplin suggests that physical vision can be deceiving, clouded by societal prejudices about class and appearance. True perception, the film argues, is a function of the heart, an ability to see another's soul regardless of external circumstances. The final scene is the ultimate exploration of this, as the girl must reconcile what her eyes now see with what her heart has always known.

Can love bridge the gap between social classes?

"City Lights" uses the romance between The Tramp and the Blind Girl to question the rigidity of social structures. The Tramp, an outcast, can only court the girl through the illusion of wealth, a pretense made possible by his sporadic friendship with the millionaire. The film critiques a world where money dictates relationships and opportunities. The central question left at the end is whether the girl's newfound awareness of The Tramp's poverty will be an insurmountable barrier or if their connection is strong enough to transcend class distinctions. The film offers a hopeful but ambiguous answer, suggesting that while love has the power to cross these divides, society's ingrained prejudices make it a difficult, perhaps even tragic, endeavor.

Alternative Interpretations

While the ending of "City Lights" is widely regarded as one of the most perfect in cinema, its ambiguity has led to various interpretations. The dominant reading is one of hopeful, transcendent love; the girl, now able to see, recognizes The Tramp's inner beauty and accepts him, fulfilling the film's central theme that love is blind to appearances.

However, a more pessimistic interpretation exists. Some critics argue that the girl's final smile is one of pity and sad resignation, not romantic acceptance. In this view, she is confronted with the harsh reality that her noble benefactor is a pathetic tramp, and the ending is a moment of heartbreak and disillusionment for both characters. The Tramp's final expression—a complex mix of hope, fear, and embarrassment—leaves his fate uncertain. Does she truly love him, or is she merely grateful? The film intentionally leaves this question open, allowing the audience to project their own hopes or cynicism onto the final frame. This ambiguity is a key part of its enduring power, forcing viewers to contemplate whether true love can truly conquer such a vast social and aesthetic gulf.

Cultural Impact

"City Lights" was released in 1931, four years after the dawn of the sound era with "The Jazz Singer." In a cinematic landscape rapidly converting to "talkies," Chaplin's decision to produce a silent film was a massive artistic and financial gamble, an act of defiance against the industry trend. The film was an immediate and resounding success, beloved by Depression-era audiences and praised by critics for its blend of comedy and pathos. It proved that the universal language of pantomime could still captivate audiences and that silent film was a legitimate art form, not just an obsolete technology.

The film's influence on cinema is immeasurable. Its final scene is frequently cited by critics, including James Agee who called it the "greatest single piece of acting ever committed to celluloid," as one of the most moving moments in film history. The structure of blending slapstick comedy with deep, sentimental romance became a hallmark for the romantic-comedy genre, which the American Film Institute ranked "City Lights" as the greatest of all time. Countless filmmakers have been influenced by its emotional depth and storytelling purity. The character of The Tramp had already made Chaplin a global icon, but this film solidified his status as a master filmmaker capable of profound emotional expression. "City Lights" remains a timeless masterpiece, continually studied and revered for its perfect balance of humor and heart, and its powerful statement on the nature of love and humanity.

Audience Reception

Upon its release in 1931, "City Lights" was met with widespread acclaim from both audiences and critics. Depression-era audiences responded enthusiastically to the film's blend of humor and heartfelt emotion, making it a major financial success with worldwide rentals exceeding $4 million. Critics praised Chaplin's genius in creating a silent film that could compete with and even surpass the new "talkies" in emotional impact and artistic merit. The film was celebrated for its masterful storytelling, its iconic comedic sequences like the boxing match, and above all, its poignantly beautiful ending. While some may have seen the silent format as dated, the overwhelming consensus was that Chaplin had created a timeless masterpiece. Its reputation has only grown over time, and it is consistently ranked among the greatest films ever made.

Interesting Facts

- The production of "City Lights" was Charlie Chaplin's longest and most arduous, taking two years and eight months to complete, with 190 days of actual shooting.

- Chaplin re-shot the scene where The Tramp first meets the flower girl 342 times because he couldn't find a satisfactory way to convey that she mistakenly thought he was wealthy.

- Despite being released well into the sound era, Chaplin defiantly made "City Lights" a silent film, albeit with a synchronized musical score and sound effects that he composed himself.

- Chaplin fired lead actress Virginia Cherrill during production after an argument. He planned to reshoot all her scenes with Georgia Hale, but realized it was too expensive and time-consuming, so he rehired Cherrill, who demanded and received double her original salary.

- The opening scene, where politicians speak with nonsensical, kazoo-like sounds, was Chaplin's satirical jab at the new "talkies." It was also the first time Chaplin's own voice was heard on film.

- Albert Einstein was Chaplin's guest of honor at the film's Los Angeles premiere, and George Bernard Shaw joined him for the London premiere.

- Orson Welles consistently named "City Lights" as his favorite film of all time.

- The film's main musical theme for the flower girl, "La Violetera," was composed by Spanish composer José Padilla. Chaplin used it without credit and later lost a lawsuit filed by Padilla.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!