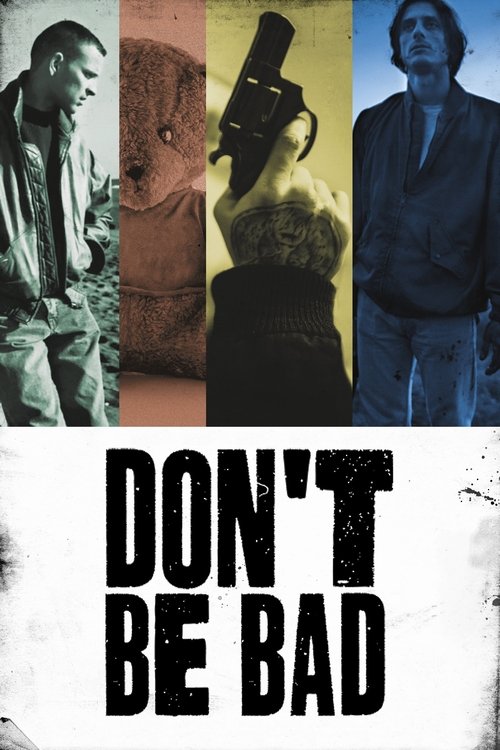

Don't Be Bad

Non essere cattivo

Overview

Set in the mid-1990s on the outskirts of Rome, Don't Be Bad (Non essere cattivo) follows the inseparable bond between Vittorio and Cesare, two young men drifting through a life of petty crime, synthetic drugs, and hedonistic abandon in the coastal town of Ostia. Their existence is a frantic cycle of cocaine-fueled nights and bleak mornings until a terrifying hallucination forces Vittorio to confront his own mortality. Seeking a way out, Vittorio attempts to swap his life of crime for the grueling stability of manual labor, finding a new anchor in a woman named Linda.

However, as Vittorio struggles to maintain his newfound sobriety and dignity, he finds himself increasingly pulled back by his loyalty to Cesare, who remains trapped in a self-destructive spiral. Cesare, burdened by the care of his terminally ill niece and a volatile temperament, represents the ghost of a life Vittorio is desperate to leave behind. The film serves as a gritty, deeply human exploration of whether one can ever truly escape the gravitational pull of their environment or if redemption is a luxury the marginalized cannot afford.

Core Meaning

The film is a poignant meditation on the impossibility of pure redemption within a decaying social structure. Director Claudio Caligari intended to portray the 'death of the Pasolinian world'—the transition of the subproletariat from a state of raw, vital innocence into a modern wasteland of chemical dependency and consumerist nihilism. The core message suggests that while 'not being bad' is a simple moral imperative, for those living on the margins, survival itself often demands the very transgressions that society condemns. It is a 'story of pure love' that transcends romance, focusing on the sacrificial and often tragic nature of brotherhood.

Thematic DNA

Brotherhood and Loyalty

The relationship between Vittorio and Cesare is the film's emotional backbone. Their loyalty is portrayed as both a saving grace and a fatal tether. Vittorio's attempt to 'save' Cesare even at the cost of his own stability highlights the theme of unconditional, fraternal love in a world that offers no other safety net.

Redemption vs. Determinism

The narrative pits the individual's will to change against the crushing weight of their social and economic environment. Vittorio represents the agonizing effort to build a 'normal' life, while Cesare embodies the tragic inevitability of a path dictated by poverty, lack of education, and addiction.

The Decay of the Pasolinian Subproletariat

Caligari explicitly references the works of Pier Paolo Pasolini, showing the evolution of the Roman 'borgata' from 1960s vitalism to 1990s drug-induced alienation. The 'badness' of the characters is framed as a symptom of a world that has lost its spiritual and cultural roots.

Addiction and Escapism

Drugs are not just a plot device but a symbol of a generation's attempt to find a 'way out' from a reality that offers no future. The transition from heroin (in Caligari's earlier work) to synthetic drugs in this film marks a shift toward a more frantic, hollow form of survival.

Character Analysis

Cesare

Luca Marinelli

Motivation

Driven by a desperate need to feel alive and a profound sense of responsibility for his sick niece, coupled with a deep-seated fear of being 'left behind' by his best friend.

Character Arc

Cesare's path is one of failed redemption. Despite his deep love for his family and his brief attempt to follow Vittorio into work, he is ultimately unable to suppress his volatile nature and the pull of his old habits, leading to his death.

Vittorio

Alessandro Borghi

Motivation

Initially fueled by the terror of death (via overdose/hallucination), his motivation shifts to providing a stable life for Linda and her son, and 'saving' Cesare from himself.

Character Arc

Vittorio undergoes a radical transformation from a drug-addicted nihilist to a man seeking stability. His arc is defined by his struggle to integrate into society while maintaining his loyalty to the doomed Cesare.

Viviana

Silvia D'Amico

Motivation

Driven by the search for affection and stability in a chaotic world, eventually focusing on the survival of her child.

Character Arc

Initially Vittorio's drug-using girlfriend, she later becomes involved with Cesare. Her arc represents the cycle of dependency and eventually the hope for a new generation.

Linda

Roberta Mattei

Motivation

Seeking a partner who can provide security for her and her son, she acts as the catalyst for Vittorio's integration into the 'straight' world.

Character Arc

She provides the alternative reality Vittorio needs—a life based on family and responsibility rather than drugs and crime.

Symbols & Motifs

The Gelato

Symbolizes repetition and the cycle of life. It is a direct homage to Caligari's debut film Amore Tossico.

The film opens with the characters arguing over a gelato on the Ostia pier, mirroring the opening of Amore Tossico and establishing the continuity of the Roman underbelly's struggle.

The Red-Shirted Teddy Bear

Represents lost innocence and premonition. The bright red color contrasts with the bleak environment, signaling blood and tragedy.

Cesare gives this plush toy to his niece, Debora, who is dying of AIDS. It serves as a reminder of the innocent victims caught in the crossfire of the characters' lifestyle.

The Construction Site

Symbolizes honest labor and the literal 'building' of a new identity. It is the antithesis of the 'fast money' of drug dealing.

Vittorio finds work as a bricklayer, using manual labor as a form of penance and a foundation for his attempt at a respectable life.

The Hallucination

Represents inner demons and the fear of a wasted life. It serves as the psychological catalyst for change.

After taking pills, Vittorio sees a terrifying figure (a killer) which triggers his realization that he must leave his current life or perish.

Memorable Quotes

Non essere cattivo.

— Multiple characters (Implicit/Explicit motif)

Context:

Derived from common parental admonishment, it echoes throughout the film as a plea for the characters to retain some shred of humanity.

Meaning:

The title serves as an ironic mantra. In the context of the film, it represents the simplistic moral advice adults give to children, which becomes tragically complex when applied to adults trapped in a brutal, systemic poverty.

Una storia degli anni novanta. Quando finisce il mondo pasoliniano.

— Claudio Caligari (Director's Note)

Context:

Often used in promotional materials and reviews to describe the film's relationship to Amore Tossico and L'odore della notte.

Meaning:

This quote frames the film's historical importance as the final chapter of a trilogy and the end of an era for the Roman subproletariat.

Ma che ce frega... volemo solo divertisse.

— Cesare

Context:

Said during one of the early scenes of drug use and partying in Ostia.

Meaning:

Expresses the hedonistic nihilism of the characters before their paths diverge; a refusal to accept the boredom of a worker's life.

Philosophical Questions

Is true redemption possible without abandoning one's past and community?

The film explores this through Vittorio's struggle; he can only succeed by distancing himself from Cesare, suggesting that redemption in a marginalized environment requires a betrayal of those who cannot change.

Does the environment determine morality, or does the individual?

By showing the characters' 'badness' as a reaction to their lack of prospects, the film questions if morality is a luxury of the stable classes, framing crime as a form of social survival.

Is 'not being bad' enough to survive in a 'bad' world?

The tragic fate of Cesare, who tries to work but fails, suggests that simple moral intentions are insufficient when systemic poverty and trauma are at play.

Alternative Interpretations

One common interpretation is that Vittorio and Cesare are two sides of the same person. Vittorio represents the 'superego' or the societal drive to conform and survive, while Cesare represents the 'id,' the raw, unbridled impulses that refuse to submit to a mundane life of labor. Their separation is not just physical but psychological, suggesting that to survive, one must 'kill' the wilder, more vital part of themselves. Another reading suggests the ending is deliberately cyclical: the birth of 'Cesare Jr.' and Vittorio's meeting with Viviana implies that the cycle of the 'borgata' will continue, with the next generation born into the same environment, questioning whether any real change has occurred.

Cultural Impact

Don't Be Bad is considered a monumental work of contemporary Italian realism. Coming 17 years after Caligari's previous film, it was hailed as the 'artistic testament' of an outsider auteur who remained faithful to his gritty vision. Its success at the Venice Film Festival and its Oscar submission revitalized interest in Caligari's earlier cult films. Culturally, it marked the breakthrough of two of Italy's most prominent modern actors, Luca Marinelli and Alessandro Borghi, whose chemistry defined a new era of Italian cinema. The film's depiction of Ostia solidified the location's status in the collective imagination as a place of cinematic tragedy and raw truth, bridging the gap between Pasolini's post-war Rome and the modern drug-fueled suburbs.

Audience Reception

The film was met with widespread critical acclaim in Italy, particularly for its performances and its uncompromising realism. Audiences praised the visceral energy and the palpable chemistry between Marinelli and Borghi, which made the tragedy of their characters deeply personal. Some international critics found the plot somewhat conventional in the 'crime drama' genre, but most were moved by its emotional depth and its status as Caligari's swan song. Controversy was minimal, though some viewers found the depiction of drug use and hallucinations jarringly intense, which the director used to emphasize the characters' fragmented reality.

Interesting Facts

- Claudio Caligari died of a tumor just a few days after finishing the film's editing; he never saw its release.

- The film was completed largely due to the efforts of actor Valerio Mastandrea, who wrote a public letter to Martin Scorsese to help secure funding for the production.

- It is the third and final installment of an ideal trilogy by Caligari that began with 'Amore Tossico' (1983) and 'L'odore della notte' (1998).

- Luca Marinelli was originally cast to play Vittorio but was switched to the role of Cesare after Alessandro Borghi joined the cast.

- The film was Italy's official submission for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 88th Academy Awards.

- The opening scene at the Ostia pier is a shot-for-shot recreation of the opening of Caligari's 1983 film 'Amore Tossico'.

- The character 'Cesare' is an auto-reference to one of the protagonists in 'Amore Tossico'.

Easter Eggs

Direct reference to Pier Paolo Pasolini's 'Accattone'.

The character Vittorio is named after the protagonist of Pasolini's Accattone, signaling that the film is a modern spiritual successor to Pasolini's explorations of the Roman margins.

Mirroring the 'Amore Tossico' gelato scene.

The discussion about gelato flavors at the start of the film is a meta-reference that connects the drug addicts of the 80s (heroin era) to those of the 90s (ecstasy era), showing that while the drugs changed, the desperation remained constant.

Citations of Scorsese's 'Mean Streets'.

The dynamic between the level-headed friend trying to improve (Vittorio) and the volatile, self-destructive one (Cesare) is a deliberate structural homage to Scorsese's classic crime drama.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!