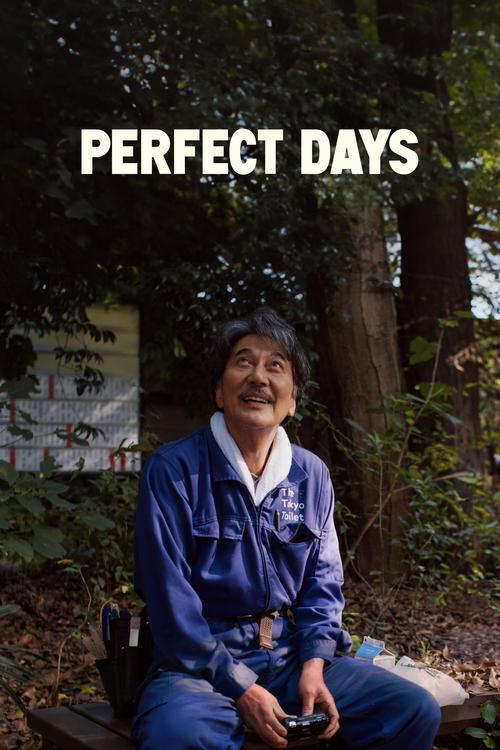

Perfect Days

PERFECT DAYS

"In a world of fleeting moments, find the beauty that lasts."

Overview

Perfect Days follows Hirayama, a middle-aged man living a life of humble simplicity in Tokyo. His days are governed by a meticulous routine: he wakes at dawn to the sound of a street sweeper, tends to his maple saplings, and drives his small van through the city to his job cleaning public toilets. Despite the seemingly lowly nature of his work, Hirayama performs his duties with the grace and precision of a master craftsman, finding deep contentment in the order and service he provides.

The film captures the quiet poetry of his existence through his hobbies—listening to classic rock on cassette tapes, reading second-hand novels by Faulkner and Highsmith, and photographing the shifting light through the trees during his lunch breaks. His solitary peace is occasionally punctured by the presence of others: a chaotic younger coworker, a mysterious homeless man, and eventually his runaway niece, Niko. These interactions provide glimpses into a complex past and the conscious choices he has made to live in the present.

Core Meaning

The core of Perfect Days is a celebration of presence and the dignity of labor. Director Wim Wenders suggests that a meaningful life is not found in grand ambitions or material wealth, but in the intentional appreciation of the here and now. The film posits that true freedom comes from accepting life's limitations and finding 'perfection' in the subtle, fleeting moments of harmony between humanity and nature, encapsulated in the Japanese concept of komorebi.

Thematic DNA

Komorebi and Impermanence

Revealed through Hirayama's daily photography and dream sequences, this theme emphasizes that every moment is unique and unrepeatable. The title itself refers to the Japanese word for sunlight filtering through leaves—a beauty that only exists for a single instant.

Solitude vs. Loneliness

The film distinguishes between being alone and being lonely. Hirayama's life is solitary but rich; his environment is filled with 'friends' like trees and music, showing that internal peace can sustain a person without the need for constant social validation.

The Beauty of Routine

By showing the same actions repeated daily, the film elevates the mundane to the sacred. Routine is portrayed as an anchor that allows for mindfulness and protection against the chaos of the modern world.

The Digital-Analog Divide

Hirayama's reliance on cassette tapes and film cameras serves as a resistance to the frantic, disposable nature of the digital age, highlighting a preference for tactile, physical connections to culture and memory.

Character Analysis

Hirayama

Koji Yakusho

Motivation

To live fully in the present moment and find peace through order, service, and the appreciation of nature.

Character Arc

Hirayama starts and ends the film in a similar state of routine, but his 'arc' is internal. Through the arrival of his niece and a meeting with his sister, we learn that his peace is a hard-won choice. He moves from a perceived simpleton to a deeply empathetic man who has intentionally rejected a life of wealth and trauma for one of service and presence.

Niko

Arisa Nakano

Motivation

To reconnect with her uncle and escape the pressures of her upper-class family life.

Character Arc

Arrives as a runaway seeking refuge from her mother's strict, wealthy world. Through her time with Hirayama, she learns the value of his perspective, moving from a girl seeking escape to one who understands that 'the world is made of many worlds.'

Takashi

Tokio Emoto

Motivation

To get money and impress a girl (Aya), viewing his work merely as a means to an end.

Character Arc

Serves as a contrast to Hirayama. He is young, loud, impatient, and obsessed with money and status. He eventually leaves the job in frustration, highlighting that the work itself is only 'perfect' if the person doing it possesses the right spirit.

Symbols & Motifs

Komorebi

Symbolizes the transience and fleeting beauty of life. It represents the specific, unique perfection found in a single moment that can never be replicated.

Visible throughout the film as Hirayama looks up at the trees during lunch, and explored in the black-and-white dream sequences at the end of each day.

Cassette Tapes

Symbolize nostalgia and a linear connection to time. Unlike digital streaming, a tape has a physical beginning and end, mirroring Hirayama's structured life.

Hirayama plays them every morning in his van, featuring artists like Lou Reed, Patti Smith, and Nina Simone, defining the mood of his journey.

Tokyo Skytree

Represents the modern, towering world that looms over Hirayama's humble, traditional existence. It serves as a visual reminder of the progress he has stepped away from.

Frequently appears in the background of Hirayama's commutes, often framed to look distant or unreachable despite being a city landmark.

The Mirror

Symbolizes meticulousness and self-reflection. It shows Hirayama's commitment to seeing things clearly and doing his job perfectly, even the parts no one else sees.

Hirayama uses a small hand mirror to inspect the undersides of the toilets he cleans, ensuring they are spotless.

Memorable Quotes

Kondo wa kondo. Ima wa ima.

— Hirayama

Context:

Said to his niece Niko while they are riding bicycles, after she suggests they go to the sea 'next time.'

Meaning:

Translates to 'Next time is next time. Now is now.' It is the film's philosophical mantra, emphasizing the importance of not worrying about the future and staying grounded in the present.

The world is made of many worlds. Some are connected, and some are not.

— Hirayama

Context:

Explaining to Niko why her mother and he live such vastly different lives.

Meaning:

Highlights the subjective nature of reality and the social silos people live in. It explains Hirayama's detachment from the high-society world of his sister.

Philosophical Questions

What constitutes a 'perfect' day?

The film argues that perfection isn't the absence of trouble, but the presence of mind. Hirayama's 'perfect' days include frustration and interruptions, yet they remain perfect because he accepts them as part of the moment.

Is routine a prison or a sanctuary?

Through the contrast between Hirayama and Takashi, the film explores how the same repetitive tasks can be soul-crushing for one person and soul-nourishing for another, depending on their internal disposition.

Alternative Interpretations

Critics and audiences have debated whether Hirayama is truly happy or if his routine is a coping mechanism for profound trauma.

- The Buddhist Reading: Hirayama has reached a state of enlightenment, having shed his ego and past attachments.

- The Melancholic Reading: The final scene, where Hirayama cries while smiling, suggests he is desperately trying to hold onto his peace against a tide of deep-seated sadness and regret over his estranged family.

- The Social Critique: Some see the film as a romanticization of low-wage labor, while others view it as a critique of a society that renders essential workers like Hirayama invisible.

Cultural Impact

Perfect Days had a significant impact on both international cinema and local tourism. It won the Best Actor award at Cannes for Koji Yakusho and was nominated for an Academy Award. In Japan, it sparked a 'toilet tourism' trend where visitors traveled to Shibuya to see the architectural toilets featured in the film. Critically, it was hailed as a return to form for Wim Wenders, blending his European sensibilities with Japanese aesthetics. Culturally, it became a touchstone for the 'slow living' movement, encouraging audiences to find beauty in the 'boring' parts of life.

Audience Reception

The film received universal acclaim from critics, holding a very high fresh rating on platforms like Rotten Tomatoes. Audiences were particularly moved by Koji Yakusho's nearly wordless performance. While a small minority of viewers found the pacing too slow or the plot 'uneventful,' the majority described it as a 'soul-cleansing' and 'profoundly moving' experience that lingered in the mind long after viewing.

Interesting Facts

- The film was shot in only 16 days.

- The project originated as a series of short promotional films for 'The Tokyo Toilet,' a real-life project featuring 17 high-tech toilets designed by world-renowned architects in Shibuya.

- Koji Yakusho worked with real professional toilet cleaners to learn their techniques before filming.

- The 4:3 aspect ratio was chosen to create a more intimate, focused look at Hirayama's world.

- The dream sequences were created and filmed by Wim Wenders' wife, Donata Wenders.

- The homeless man in the film is played by Min Tanaka, a famous Japanese avant-garde dancer and 'Butoh' performer.

- The film was Japan's official entry for the 96th Academy Awards, the first time a non-Japanese director's film was chosen.

Easter Eggs

Reference to Yasujiro Ozu

The protagonist's name, Hirayama, is the same as the lead character in Ozu's final film, An Autumn Afternoon. Wenders has frequently cited Ozu as his greatest cinematic influence, and the film's pace and framing mirror Ozu's style.

The 'Shadow Tag' scene

The interaction between Hirayama and the stranger (Mama's ex-husband) about whether shadows get darker when they overlap is a literal exploration of the film's visual motif of light and shadow.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!