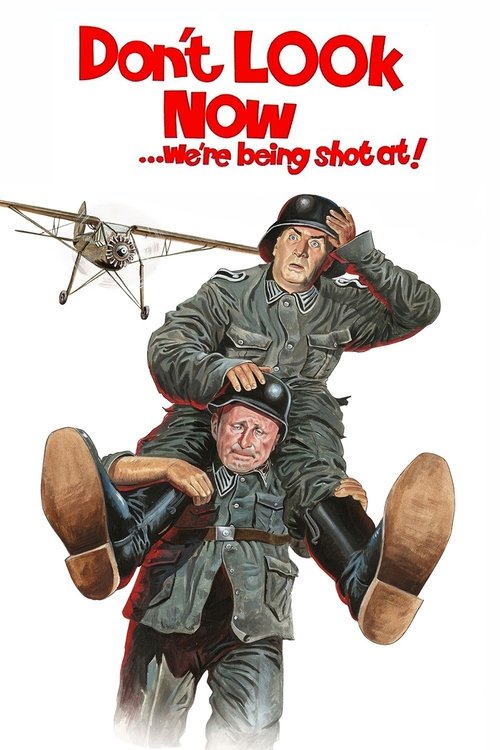

Don't Look Now... We're Being Shot At!

La Grande Vadrouille

Overview

“Don't Look Now... We're Being Shot At!” (Original Title: “La Grande Vadrouille”), released in 1966, is a celebrated French comedy set during World War II. The story begins in 1942 when a Royal Air Force bomber is shot down over German-occupied Paris. The three English crew members parachute to safety, landing in different parts of the city. Their only instruction is to rendezvous at the Turkish baths at the Grand Mosque of Paris.

This sets the stage for an unlikely alliance between two French civilians and the British airmen. Augustin Bouvet (Bourvil), a good-natured house painter, and Stanislas Lefort (Louis de Funès), a cantankerous and egotistical conductor at the Opéra Garnier, are inadvertently drawn into the conflict when they help two of the airmen. What follows is a frantic and hilarious journey as this mismatched pair attempts to guide the British soldiers across France to the safety of the free zone, all while being relentlessly pursued by the German Major Achbach (Benno Sterzenbach).

The film masterfully blends action, adventure, and slapstick comedy, creating a series of now-classic scenes as the group navigates the perils of occupied France with the help of various Resistance sympathizers, including a puppet master's granddaughter and a compassionate nun. The dynamic between the humble, easy-going Bouvet and the pompous, high-strung Lefort provides the heart of the film's comedy.

Core Meaning

The core meaning of “Don't Look Now... We're Being Shot At!” lies in its celebration of national unity and solidarity in the face of oppression, transcending social class barriers. Director Gérard Oury sought to create a comedy that could laugh at a tragic period of French history, the German Occupation, without trivializing the underlying gravity. The film posits that ordinary people, regardless of their courage or initial convictions, can become heroes when circumstances demand it. It served as a comforting narrative for a post-war France, promoting a myth of widespread resistance and national unity against the occupier. By focusing on the interpersonal relationships and the comedic friction between its main characters, the film suggests that shared humanity and a common goal can bridge even the widest social divides, turning a simple painter and a prestigious conductor into unlikely patriots and friends.

Thematic DNA

Unlikely Heroes and Civilian Courage

The central theme revolves around ordinary individuals rising to extraordinary circumstances. Neither Augustin Bouvet nor Stanislas Lefort are traditional heroes; they are civilians inadvertently caught in the war. Their journey from reluctant accomplices to active participants in the Resistance illustrates the idea that heroism is not innate but a choice made in critical moments. The film celebrates the courage of common citizens who, despite their fears, contribute to the fight for freedom.

Social Class and Solidarity

The film creates a powerful comedic duo by contrasting the working-class, humble painter Augustin with the upper-class, arrogant conductor Stanislas. Their initial interactions are marked by class friction and disdain. However, their shared perilous journey forces them to rely on each other, breaking down social barriers and forging an unexpected friendship. This theme suggests that national solidarity can overcome internal social divisions, a poignant message for post-war France.

National Identity and the Myth of Resistance

Released two decades after the end of WWII, the film played a significant role in shaping France's collective memory of the Occupation. It presented a comforting and unifying myth of near-universal French resistance against the Germans, downplaying the historical complexities of collaboration. This portrayal of a nation united in defiance resonated deeply with French audiences and helped solidify a heroic national identity.

The Absurdity of War

While set against a grim backdrop, the film uses comedy and burlesque situations to highlight the absurdity of war. By having the German officers often appear incompetent and easily fooled, and by focusing on slapstick and elaborate chase sequences rather than bloodshed, the film strips the conflict of its terror and reframes it as a chaotic, almost surreal adventure. This approach allows the audience to engage with a difficult historical period through the catharsis of laughter.

Character Analysis

Augustin Bouvet

Bourvil

Motivation

Initially motivated by a basic sense of duty and empathy, Augustin's primary motivation becomes loyalty to the people he has sworn to help and a growing sense of patriotic responsibility, spurred on by his burgeoning affection for Juliette.

Character Arc

Augustin begins as a simple, good-natured house painter who wants no trouble. He is kind and unassuming. Through his forced partnership with Stanislas and his commitment to helping the British airmen, he discovers a quiet courage and resourcefulness he never knew he had, becoming a dependable and brave member of the group.

Stanislas Lefort

Louis de Funès

Motivation

His initial motivation is pure self-preservation. He helps the airmen only because he fears the consequences of not doing so. This evolves into a desire to protect his newfound companions and a grudging acceptance of his patriotic duty.

Character Arc

Stanislas starts as a comically arrogant, self-important, and cowardly conductor, concerned only with his own comfort and career. Dragged into the escape against his will, the perilous journey humbles him. He slowly sheds his selfishness, forms an unlikely bond with Augustin, and ultimately embraces his role in the resistance, even taking command in critical moments.

Sir Reginald Brook

Terry-Thomas

Motivation

As a British officer, his motivation is clear and unwavering: to evade capture, reunite his crew, and return to Allied territory to continue fighting the war. He is driven by duty and patriotism.

Character Arc

Sir Reginald, known as "Big Moustache," remains a steadfast and unflappable leader throughout the film. His arc is less about personal change and more about adapting his military command style to the chaotic civilian world of the French Resistance. He maintains his British stiff upper lip and sense of humor even in the most absurd situations, providing a comic contrast to his French helpers.

Juliette

Marie Dubois

Motivation

Juliette is motivated by her strong patriotic convictions and her desire to help the Allied cause. She risks her own safety without hesitation to aid the escaping airmen and their French companions.

Character Arc

Juliette is a brave and resourceful young woman from the very beginning. Working as a puppeteer, she is already involved with the Resistance. Her arc involves her growing affection for the British airman Peter Cunningham and her role as a steady, capable guide for the bumbling heroes, representing the steadfast and courageous spirit of the French people.

Symbols & Motifs

The Parachutes

The parachutes symbolize the sudden and disruptive intrusion of the war into the everyday lives of ordinary French citizens. They literally drop the conflict from the sky and onto the doorsteps of Augustin and Stanislas, forcing them out of their routines and into the larger historical narrative.

At the beginning of the film, the British airmen's white parachutes descend upon Paris, with one landing on Augustin's scaffolding and another on the roof of the Opéra Garnier where Stanislas is conducting. This event is the catalyst for the entire plot.

Shoes and Bicycles

The recurring motif of shoes and bicycles symbolizes the social and physical struggles of the journey, as well as the shifting power dynamic between Stanislas and Augustin. Control over these basic items of transport represents a small victory or a moment of leverage in their desperate situation.

There are several scenes where shoes become a point of contention, most notably when the arrogant Stanislas ends up with Augustin's more practical footwear. Augustin's lament, "Mon vélo, mes chaussures..." ("My bike, my shoes...") becomes a recurring, comedic expression of his exasperation.

The Turkish Baths (Hammam)

The Turkish baths symbolize a neutral, liminal space where identities are blurred and unexpected alliances are formed. The steam and anonymity of the location allow for a clandestine meeting, but also create immense comedic confusion, highlighting the precarious nature of their mission.

The British airmen designate the Turkish baths at the Grand Mosque of Paris as their rendezvous point. The famous scene involves Augustin and Stanislas, who have never met, attempting to identify their English contact, "Big Moustache," by whistling "Tea for Two," leading to a hilarious misunderstanding where they realize they are both French.

Pumpkins

The pumpkins symbolize the rustic, unassuming, and surprisingly effective nature of the French resistance. What appears to be a simple vegetable becomes a chaotic and effective weapon against the technologically superior German forces, representing the triumph of ingenuity and resourcefulness over brute force.

In a memorable chase scene, the heroes use a cart full of pumpkins, rolling them down a hill to thwart their German pursuers. The absurdity of using pumpkins as weapons is a prime example of the film's burlesque humor.

Memorable Quotes

Y a pas d'hélice hélas. - C'est là qu'est l'os !

— Peter Cunningham and Augustin Bouvet

Context:

This exchange occurs when assessing a vehicle for their escape, realizing a crucial part is missing. It's a moment of comic despair that has become one of the most famous lines from the film.

Meaning:

A classic French pun that translates to "There's no propeller, alas. - That's where the bone is!" The humor comes from the play on words, as "l'os" (the bone) sounds like "le last," playing on the idea of a final problem. It exemplifies the film's lighthearted and witty dialogue even in moments of peril.

But alors, you are French?!

— Stanislas Lefort

Context:

In the Turkish baths, Stanislas and Augustin are trying to find "Big Moustache." Thinking the other is English, they struggle to speak to each other until Augustin, in frustration, blurts out a French curse word, leading to Stanislas's shocked and hilarious realization.

Meaning:

This quote is the comedic climax of the Turkish baths scene. After a prolonged and confused attempt to communicate in broken English, both Stanislas and Augustin realize they are French. The line perfectly captures the absurdity of their situation and the initial lack of trust and communication between them.

Ils peuvent me tuer, je ne parlerai pas! - Mais moi non plus, ils peuvent vous tuer, je ne parlerai pas!

— Augustin Bouvet and Stanislas Lefort

Context:

While captured by the Germans, Augustin makes a brave declaration. Stanislas appears to second the sentiment, but cleverly twists it to ensure his own safety at Augustin's expense, much to Augustin's dawning horror and the audience's amusement.

Meaning:

Translating to "They can kill me, I won't talk! - Me neither, they can kill you, I won't talk!", this quote perfectly encapsulates Stanislas's cowardly and self-centered nature in a darkly humorous way. It highlights the stark contrast between Augustin's genuine bravery and Stanislas's comical self-preservation.

Mon vélo, mes chaussures... et puis quoi maintenant ?

— Augustin Bouvet

Context:

Augustin says this in exasperation after Stanislas has managed to appropriate both his comfortable shoes and his bicycle for his own use, leaving Augustin to suffer.

Meaning:

"My bicycle, my shoes... and now what?" This line is a recurring lament from Augustin, humorously summarizing his constant state of being put-upon by the demanding and manipulative Stanislas. It embodies the theme of class difference and the personal sacrifices he has to make.

Philosophical Questions

What is the nature of everyday heroism?

The film explores the idea that heroism isn't limited to soldiers or designated leaders. It portrays courage as a quality that can emerge from ordinary people when they are confronted with moral choices. Augustin and Stanislas are not brave by nature; their heroism is situational and develops out of a series of reluctant decisions. The film asks what motivates someone to risk their life for another and suggests that it often stems from basic human decency and solidarity rather than grand ideology.

Can comedy be an effective tool for processing historical trauma?

By making a comedy about the German Occupation, a deeply traumatic period in French history, the film raises questions about the role of humor in confronting the past. “La Grande Vadrouille” uses laughter not to erase the pain of the past, but to make it bearable and to celebrate the resilience of the human spirit. It proposes that by ridiculing the oppressors and focusing on the absurdity of the situation, a collective trauma can be processed and a positive, unifying narrative can be constructed, even if it is a mythologized one.

Do societal roles and class distinctions matter in the face of a common threat?

The film directly confronts the issue of social class through the relationship between the working-class Augustin and the bourgeois Stanislas. Initially, their interactions are defined by their social positions. However, as they face shared dangers, these distinctions become increasingly irrelevant. The film suggests that fundamental human qualities like loyalty and courage are more important than social status, and that true unity is forged through shared experience and a common purpose, rendering class structures meaningless.

Cultural Impact

“La Grande Vadrouille” is more than just a successful comedy; it is a cultural institution in France. For over four decades, it held the title of the most-watched film in French history, a testament to its enduring appeal across generations. Its frequent television broadcasts continue to draw millions of viewers, solidifying its place in the nation's collective memory.

Historically, the film was released at a time when France was ready to look back at the Occupation with a different lens. Gérard Oury's decision to make a comedy about such a dark period was audacious. The film's immense success helped to create and perpetuate a unifying national myth of widespread resistance against the German occupiers. This narrative, while simplifying a complex history of collaboration and attentisme (wait-and-see attitude), provided a sense of national pride and comfort in the post-war decades. It presented an image of ordinary Frenchmen as inherently brave and patriotic, capable of uniting against a common enemy regardless of their social standing.

Critically, the reception was more mixed at the time, with some critics finding the humor too broad or inappropriate for the subject matter. However, the public's overwhelming embrace of the film cemented its legacy. It set a new standard for French popular cinema, demonstrating that a big-budget comedy could achieve massive success and cultural resonance. The film's influence can be seen in its pairing of a comedic duo from different social classes, a formula that has been revisited in subsequent French comedies. Its success proved that popular entertainment could also serve as a form of cultural storytelling, shaping how a nation viewed one of the most challenging periods of its history.

Audience Reception

The audience reception for “La Grande Vadrouille” was, and remains, overwhelmingly positive, particularly in France where it is considered a national treasure. Upon its release in 1966, it became a box-office phenomenon, selling over 17 million tickets and remaining the most successful film in French history for 42 years. Audiences adored the comedic chemistry between Bourvil and Louis de Funès, whose contrasting personalities created a perfect duo. The film’s blend of slapstick, witty dialogue, and high-stakes adventure resonated deeply, making it a beloved classic for family viewing. Viewers praised its good-natured humor, memorable scenes like the Turkish baths encounter, and the satisfying ridicule of the Nazi antagonists. While some contemporary critics were mixed, arguing the humor was too simplistic or vulgar for the subject matter, the audience's verdict was unequivocal. The film's enduring popularity is evident in its high television ratings with each broadcast, as generations continue to embrace its heartwarming story of unlikely heroes.

Interesting Facts

- The film was the most successful film in France for over 40 years, with more than 17.2 million tickets sold, a record only broken in 1998 by 'Titanic'.

- This was the final collaboration between the iconic comedic duo Bourvil and Louis de Funès.

- The screenplay was co-written by director Gérard Oury and his daughter, Danièle Thompson, marking her debut as a screenwriter.

- For the scene where he conducts the orchestra at the Opéra Garnier, Louis de Funès spent three months rehearsing the conducting movements to ensure his performance was authentic. The musicians were so impressed that they acclaimed him in the traditional way by tapping their bows on their instruments, an unscripted moment that was kept in the film.

- The famous piggyback scene, where Augustin carries Stanislas, was not in the original script and was improvised by the two lead actors.

- The film was shot at the Billancourt Studios in Paris and on location across France, including at the notable Hospices de Beaune.

- The original scenario for the film was about two sisters helping the airmen, but Gérard Oury decided to change them to men to reunite the successful duo of Bourvil and de Funès from his previous film, 'Le Corniaud'.

- 'La Grande Vadrouille' was one of the first French films to use comedy to address the sensitive period of the German Occupation.

- In Germany, it was the very first comedy about World War II to be shown in cinemas.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!