La Haine

"How far you fall doesn't matter, it's how you land…"

Overview

"La Haine" (Hate) chronicles twenty-four hours in the lives of three young friends from an impoverished and racially diverse housing project in the suburbs of Paris. The film is set in the aftermath of a violent riot that has left their friend, Abdel Ichaha, in a coma after a brutal police interrogation. The narrative follows Vinz (Vincent Cassel), a volatile Jewish youth, Hubert (Hubert Koundé), a thoughtful Afro-French boxer, and Saïd (Saïd Taghmaoui), a sharp-witted North African. Their day is a mixture of aimless wandering, humorous banter, and tense confrontations, all underscored by the discovery that Vinz has found a policeman's lost revolver.

As the trio navigates their bleak surroundings and ventures into the heart of Paris, they encounter a society that views them with suspicion and hostility. The film explores their differing perspectives on their situation: Vinz's desire for revenge, Hubert's yearning for escape, and Saïd's role as a mediator. The ticking clock of Abdel's fate and Vinz's vow to kill a cop if he dies creates a palpable tension that builds throughout the film, leading to a shocking and unforgettable climax.

Core Meaning

The core message of "La Haine" is encapsulated in Hubert's recurring line, "La haine attire la haine" (hatred breeds hatred). Director Mathieu Kassovitz sought to expose the vicious cycle of violence and prejudice that traps marginalized youth in the French 'banlieues' (suburbs). The film is a powerful social commentary on police brutality, systemic inequality, and the disenfranchisement of immigrant communities. It doesn't offer easy answers but rather holds up a mirror to a society in crisis, as symbolized by the story of a man falling from a skyscraper who repeats to himself, "So far, so good..." — it's not the fall that matters, but the landing. Kassovitz intended to put a human face on the statistics of urban violence, making the audience understand the individuals behind the news headlines of riots and arrests.

Thematic DNA

Police Brutality and Institutional Racism

The film is a direct response to real-life instances of police violence in France, such as the deaths of Makomé M'Bowolé and Malik Oussekine. It portrays the police as an antagonistic force, engaging in harassment, abuse, and unwarranted violence against the protagonists. The power imbalance is a constant source of conflict, fueling the characters' anger and resentment. However, the film avoids a completely one-sided portrayal by including a police officer who tries to help the youths, suggesting the problem is systemic rather than solely individual.

Social Exclusion and Marginalization

"La Haine" vividly depicts the physical and social isolation of the 'banlieues' from the affluent center of Paris. The protagonists are treated as outsiders in their own country, facing prejudice and discrimination based on their race and class. Their journey into Paris highlights this cultural divide, where they are met with suspicion and hostility, reinforcing their sense of not belonging to mainstream French society. This theme is explored through their interactions in spaces like the art gallery, where their presence is immediately questioned.

The Cycle of Violence and Hatred

The film's title, which translates to "Hate," is its central theme. Hubert's line, "hatred breeds hatred," serves as the film's thesis, arguing that violence only perpetuates more violence. Vinz's desire for revenge and his possession of the gun symbolize the temptation to break this cycle through further aggression, a path Hubert warns against. The film's tragic ending underscores the destructive and inescapable nature of this cycle, suggesting that in an environment fueled by hate, there are no winners.

Youth and Identity

The film captures a generation of young people caught between the culture of their immigrant parents and French society, finding a shared identity in American hip-hop and cinema. Vinz, Hubert, and Saïd, despite their different ethnic backgrounds (Jewish, Black, and Arab), are united by their shared social exclusion. They grapple with their identities and futures in a world that seems to offer them no opportunities. Vinz's posturing and imitation of Travis Bickle from "Taxi Driver" is a poignant example of this search for a powerful identity in a powerless situation.

Character Analysis

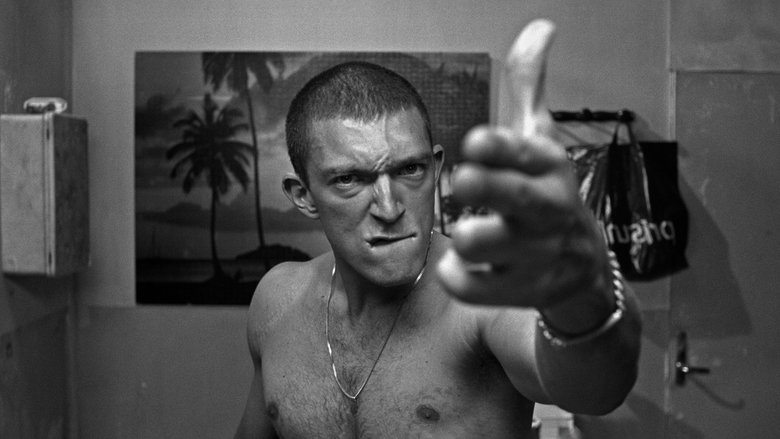

Vinz

Vincent Cassel

Motivation

His primary motivation is to avenge his friend Abdel and gain respect in a system that marginalizes him. He believes that violence is the only language the system understands and that possessing the gun gives him the power to "re-establish balance."

Character Arc

Vinz begins the film as an aggressive and short-tempered youth, consumed by a desire for revenge against the police. He performs a tough exterior, famously imitating Travis Bickle from "Taxi Driver." His arc is one of realizing the difference between posturing and the reality of violence. After having the chance to kill a skinhead and being unable to do it, he recognizes that he is not a killer. His decision to hand the gun to Hubert in the final moments represents a significant moral growth, making his subsequent death all the more tragic.

Hubert

Hubert Koundé

Motivation

Hubert is motivated by a desire to leave the violence and poverty of the projects behind. He wants a better life for himself and his family, whom he supports through small-time drug dealing. His core belief is that "hatred breeds hatred," and he tries to convince his friends to choose a different path.

Character Arc

Hubert is the most mature and contemplative of the trio, an Afro-French boxer who dreams of escaping the 'banlieue'. His gym, a symbol of hope, was destroyed in the riots. Throughout the film, he acts as a moral compass, constantly warning Vinz about the consequences of hatred. His arc is tragic; despite his efforts to remain above the violence, he is ultimately drawn into it. The final scene, where he is left pointing a gun at a cop, suggests that the cycle of hate may be impossible to escape, even for the most level-headed.

Saïd

Saïd Taghmaoui

Motivation

Saïd's motivation is to navigate the daily realities of his life, maintain the friendship between the three, and find moments of levity amidst the tension. He is curious and seeks excitement but is ultimately caught in the same systemic trap as his friends.

Character Arc

Saïd, a young North African Muslim, often acts as the mediator between the hot-headed Vinz and the philosophical Hubert. He is often playful and tries to defuse tension with humor, but he is also deeply aware of the injustices they face. His arc is less about transformation and more about observation. The film opens and closes on his eyes, positioning him as the witness to the tragedy. In the end, he is left as the sole observer of the violent climax, his wide-eyed shock representing the audience's horror.

Symbols & Motifs

The Falling Man/Society Story

This recurring story, told by Hubert, about a man falling from a skyscraper who tells himself "so far, so good" on the way down, is an allegory for French society. It symbolizes a society in denial, ignoring its deep-seated problems and heading for a catastrophic landing. The final iteration of the story changes "a man" to "a society," making the film's critique explicit.

The story bookends the film, appearing in the opening and closing narration. It serves as a framework for understanding the entire narrative, suggesting that the 24 hours we witness are just a moment in a larger, inevitable descent into chaos.

The Gun

The lost police revolver that Vinz finds symbolizes power, the potential for violence, and the central moral dilemma of the film. For Vinz, it represents a means of gaining respect and enacting revenge in a world that has rendered him powerless. For Hubert, it is a dangerous object that will only perpetuate the cycle of hate. The transfer of the gun from Vinz to Hubert at the end signifies a shift in responsibility and Vinz's ultimate rejection of violence.

The gun is a central plot device, introduced early on after the riots. Vinz carries it throughout the film, creating constant tension. Key scenes involving the gun include Vinz's confrontation with a skinhead and the final, tragic standoff with the police.

The Ticking Clock

The on-screen display of the time throughout the film creates a sense of impending doom and urgency. It functions as a countdown, suggesting that time is running out for the characters and the society they inhabit. This device reinforces the film's structure, which chronicles a specific 24-hour period, and amplifies the tension as the narrative moves towards its inevitable conclusion.

The time is frequently superimposed on the screen, marking the progression of the day and night. This technique gives the film a documentary-like feel of chronicling events as they unfold.

The Cow

The surreal image of a cow appearing in the housing project symbolizes the absurdity and displacement felt by the characters. It represents something out of place, much like the protagonists feel in their own society. For Vinz, who is the only one to see it, it could represent his inner turmoil and the strangeness of his reality. In Jewish culture, seeing a cow in a dream can be an omen of death, foreshadowing Vinz's fate.

The cow appears unexpectedly as the friends are talking on a rooftop. The other characters dismiss Vinz's sighting, adding to the surreal and isolating nature of the vision.

Memorable Quotes

C'est l'histoire d'un mec/d'une société qui tombe et au fur et à mesure de sa chute, il/elle se répète sans cesse pour se rassurer : 'Jusqu'ici tout va bien, jusqu'ici tout va bien, jusqu'ici tout va bien.' L'important, c'est pas la chute, c'est l'atterrissage.

— Hubert

Context:

This line is delivered by Hubert in voiceover at the beginning of the film, and a variation of it is repeated at the very end. It frames the entire narrative and encapsulates the film's core message about societal decay.

Meaning:

Translation: "It's the story of a guy/a society who falls and on his/its way down, he/it keeps telling himself/itself to be reassured: 'So far, so good, so far, so good, so far, so good.' The important thing isn't the fall, it's the landing." This quote is the central metaphor of the film, comparing the precarious state of the 'banlieues' and French society to a person in freefall, unaware or in denial of the inevitable, disastrous impact.

La haine attire la haine.

— Hubert

Context:

Hubert says this to Vinz during one of their arguments about the gun and the idea of revenge. It's a direct challenge to Vinz's belief that more violence is the answer to their problems.

Meaning:

Translation: "Hatred breeds hatred." This simple but profound statement is the film's thesis. It articulates Hubert's philosophy and the director's warning about the self-perpetuating cycle of violence that stems from social injustice and police brutality.

Avec un truc comme ça, t'es le boss dans la cité.

— Saïd

Context:

Saïd says this to Vinz when he first sees the stolen revolver, highlighting the immediate association between the gun and power within their environment.

Meaning:

Translation: "With a thing like that, you're the boss in the projects." This quote reflects the allure of power that the gun represents to the disenfranchised youths. In a world where they feel powerless, the weapon is seen as a way to gain status and respect.

On n'est pas à Thoiry ici.

— Hubert

Context:

The trio is on a rooftop in their housing project when they notice journalists filming them from a nearby building. Hubert shouts this line, expressing his frustration at their voyeuristic gaze.

Meaning:

Translation: "We're not in Thoiry here." Thoiry is a French safari park where visitors observe animals from a safe distance. Hubert's comment is a sharp rebuke to journalists who are filming them from afar as if they were animals in a zoo. It powerfully expresses his anger at being objectified and dehumanized by the media and mainstream society.

Philosophical Questions

Does violence justify violence?

This is the central philosophical question debated by Vinz and Hubert. Vinz believes in an "eye-for-an-eye" justice, arguing that killing a cop is necessary to "re-establish the balance." Hubert counters with the philosophy that "hatred breeds hatred," arguing that violence is a self-perpetuating cycle that solves nothing. The film explores this question without offering a simple answer, culminating in a tragic climax where violence, both accidental and deliberate, leads only to more death and despair.

Can one escape their environment?

Hubert's character embodies the struggle to escape the 'banlieue'. He dreams of leaving and tries to maintain a moral code separate from the street, but his environment constantly pulls him back. His boxing gym, a potential escape route, is destroyed in the riots. The film questions whether individual will is enough to overcome systemic poverty, prejudice, and violence. The ending suggests a pessimistic view, implying that the forces of one's environment and the cycle of hatred are ultimately inescapable.

What is the nature of identity in a multicultural society?

The film presents a "black-blanc-beur" (black-white-Arab) trio, representing the multicultural makeup of the French suburbs. Despite their different ethnic and religious backgrounds, they are united by a common social identity defined by their exclusion from mainstream French society. The film explores how their identities are forged in opposition to the state and in solidarity with each other, challenging the traditional French model of assimilation.

Alternative Interpretations

The film's ambiguous ending has been a subject of much debate. After Vinz is accidentally killed by a cop, Hubert points his gun at the officer, who does the same. The screen cuts to black as a gunshot is heard, leaving the audience to wonder who shot whom. One interpretation is that Hubert, despite his principles, succumbs to the cycle of hate and shoots the cop. Another is that the cop shoots Hubert, reinforcing the idea of an oppressive and unaccountable system. A third possibility is that Hubert, in a moment of despair, takes his own life. The ambiguity is intentional, forcing the audience to confront the question of where the violence ends. Kassovitz shifts the focus from the individual outcome to the overarching tragedy of a society where such a confrontation is inevitable. The final shot of Saïd's face, caught between the two armed men, represents the audience and a society trapped in the crossfire.

Cultural Impact

"La Haine" was a cultural phenomenon in France and beyond, sparking a national conversation about police brutality, racism, and life in the 'banlieues'. Released in 1995, its timing was prescient, as riots erupted in French suburbs shortly after its release, with some media outlets even blaming the film for inciting unrest. The film's raw, unflinching portrayal of a marginalized segment of French society was a stark departure from the typical depiction of Paris in cinema. It gave a voice to the voiceless and brought the reality of the projects into the mainstream consciousness.

Winning Best Director for Mathieu Kassovitz at the Cannes Film Festival brought it international acclaim and solidified its place as a landmark of world cinema. Its influence can be seen in numerous subsequent films that deal with social unrest and urban youth, such as "Ma 6-T va crack-er" and Ladj Ly's "Les Misérables" (2019). The film's aesthetic, blending gritty realism with stylistic flourishes inspired by American cinema like Spike Lee's "Do the Right Thing," had a lasting impact. Despite being 25 years old, its themes remain disturbingly relevant, resonating with contemporary movements like Black Lives Matter and ongoing debates about inequality and policing worldwide.

Audience Reception

Upon its release, "La Haine" was met with both widespread critical acclaim and significant controversy. Audiences and critics praised its raw energy, powerful performances by the three leads, and stylish, innovative direction. It was lauded for its social relevance and for bringing a previously unseen side of France to the screen. However, the film was heavily criticized by police organizations and some politicians for its perceived anti-police stance. Some viewers found the film's portrayal of violence and its confrontational tone unsettling. Despite the controversy, it was a commercial success in France and achieved cult classic status internationally, with many considering it a vital and timeless masterpiece that remains disturbingly relevant decades later.

Interesting Facts

- The film was inspired by the real-life killing of Makomé M'Bowolé, a 17-year-old from Zaire, who was shot and killed by police while in custody in 1993.

- Director Mathieu Kassovitz started writing the script on the day of Makomé M'Bowolé's death.

- The film was shot in black and white to give it a timeless, documentary-like feel and to emphasize the grim reality of the 'banlieues'.

- To achieve authenticity, the cast and crew lived in the Chanteloup-les-Vignes housing project for three months before and during filming.

- Mathieu Kassovitz has a cameo in the film as a skinhead who Vinz confronts.

- The famous scene where Vinz talks to himself in the mirror was filmed without a mirror. A body double mimicked Vincent Cassel's movements in a reversed set.

- French police unions were angered by the film's depiction of police brutality and called for a boycott upon its release. Officers reportedly turned their backs on the film's team during a ceremonial guard at the Cannes Film Festival.

- Then-Prime Minister Alain Juppé commissioned a special screening of the film for his cabinet to help them understand the issues in the suburbs.

Easter Eggs

Vinz's 'You talkin' to me?' scene

In his bathroom, Vinz mimics Robert De Niro's iconic Travis Bickle character from the film "Taxi Driver" (1976). This is a direct homage and a key character moment, showing Vinz's identification with an alienated, violent anti-hero as he grapples with his own anger and sense of powerlessness.

DJ Cut Killer's 'Sound of da Police' Mix

In a memorable aerial tracking shot over the estate, the real-life French hip-hop DJ Cut Killer scratches a mix that blends Edith Piaf's "Non, je ne regrette rien" with KRS-One's "Sound of da Police" and French rap group NTM's "Nique la Police" ("Fuck the Police"). This mix powerfully symbolizes the cultural fusion and the anti-authoritarian sentiment of the 'banlieue' youth.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!