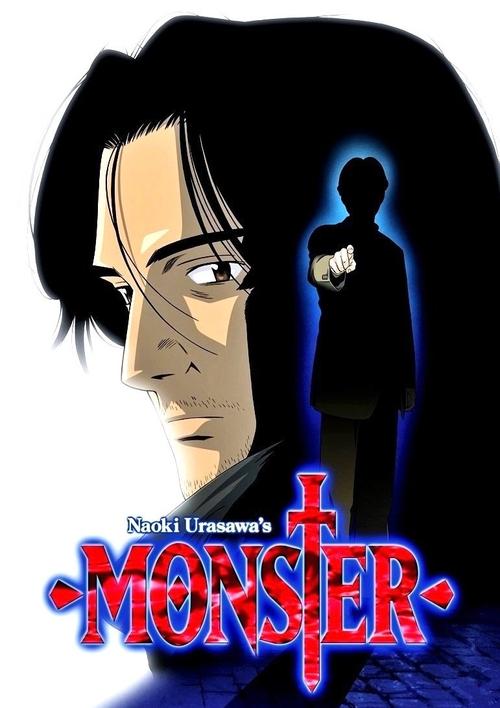

Monster

MONSTER

"The only thing humans are equal in is death."

Overview

"Monster" follows Dr. Kenzo Tenma, a brilliant Japanese neurosurgeon living in Germany, whose idyllic life shatters after he makes a fateful choice. He chooses to operate on a young boy named Johan Liebert, who has a gunshot wound to the head, instead of the city's mayor, based on the principle that all lives are equal. This decision costs him his prestigious position and his engagement to the hospital director's daughter, Eva Heinemann. However, a few years later, a series of mysterious deaths reinstates Tenma's career, and he comes to the horrifying realization that the boy he saved has grown into a charismatic, sociopathic serial killer.

Wracked with guilt and implicated in the murders himself, Tenma abandons his life and goes on the run. His journey becomes a relentless manhunt across Germany and the Czech Republic to find and stop Johan, the titular "monster" he feels responsible for unleashing upon the world. Along the way, he encounters a diverse cast of characters affected by Johan's manipulations, including Johan's amnesiac twin sister, Nina Fortner, and the tenacious BKA Inspector Lunge, who is convinced Tenma is the true killer.

The series delves deep into the origins of Johan's evil, tracing it back to a clandestine East German orphanage, Kinderheim 511, which conducted psychological experiments on children. As Tenma peels back the layers of conspiracy and forgotten memories, he grapples with profound philosophical questions about the nature of humanity, the value of life, and whether he must become a monster himself to stop one. The narrative is a complex web of suspense, character studies, and historical context, set against the backdrop of post-reunification Germany.

Core Meaning

The core meaning of "Monster" revolves around an exploration of the human condition, questioning the origins of evil and the inherent value of life. It posits that "monsters" are not born but created through abuse, psychological manipulation, and the failure of others to show love and compassion. The series relentlessly examines the nature versus nurture debate, suggesting that the monster inside each person is a product of their environment and choices. Ultimately, the message is one of cautious hope, asserting that despite the existence of profound darkness, humanity's capacity for empathy, forgiveness, and the belief in the equality of all lives are the only forces that can counter it. The story challenges the audience to define what a monster truly is, pointing fingers not just at the villain, but at the systems and individuals who created him.

Thematic DNA

The Nature of Good and Evil

The series constantly blurs the line between good and evil. Dr. Tenma, the epitome of a moral and life-saving doctor, is forced to contemplate murder to stop Johan. His journey is a descent into a moral gray area, challenging his core belief that all lives are equal. Conversely, Johan, the seemingly pure evil antagonist, is revealed to be a product of horrific psychological experiments and trauma, making him a tragic figure as well as a monstrous one. The series suggests that evil is not an inherent quality but a corruption of the human spirit, often born from suffering.

The Value and Equality of Life

The central philosophical conflict begins with Tenma's decision to save a common boy over a mayor, founded on the principle that all lives are created equal. This belief is directly challenged by Johan, whose nihilistic worldview culminates in the assertion that the only thing equal for all is death. Throughout the 74 episodes, Tenma's initial ideology is tested to its limits as he confronts the consequences of saving a life that would go on to extinguish so many others. His ultimate decision to save Johan again at the end reaffirms his unwavering, albeit difficult, adherence to his core principle.

Identity and Namelessness

Many characters in "Monster" struggle with their identities. Johan's primary goal is to achieve a "perfect suicide" by erasing his own existence, leaving no trace that he ever lived. His lack of a true name for much of his life is central to his monstrous nature; he is the "Nameless Monster" from a Czech storybook. Nina, his twin, suffers from amnesia, piecing together her traumatic past to reclaim her identity. Even Inspector Lunge sacrifices his personal life and identity for his work, becoming an extension of his obsessive hunt for Tenma. The series explores how identity is shaped by memory, names, and the love (or lack thereof) received from others.

The Scars of the Past

Set in post-Cold War Germany, the series uses its setting to reflect how historical traumas haunt the present. The legacy of Nazi eugenics and Soviet-era psychological experiments are the crucible in which Johan was formed. Characters are constantly confronted by the consequences of their past actions and the buried secrets of institutions like Kinderheim 511. The narrative suggests that personal and societal pasts cannot be escaped and must be confronted to be overcome. The fall of the Berlin Wall serves as a backdrop for a world where old ideologies and sins cast long shadows.

Character Analysis

Dr. Kenzo Tenma

Hidenobu Kiuchi

Motivation

Initially motivated by a strong sense of medical ethics and the belief in the sanctity of life, Tenma's motivation shifts to a deep-seated guilt and sense of responsibility for unleashing Johan upon the world. His primary drive becomes stopping Johan at any cost to atone for his perceived mistake and to prevent further suffering. This singular focus consumes nearly a decade of his life.

Character Arc

Tenma begins as a brilliant, morally upright surgeon who believes all lives are equal. After saving Johan, his life is destroyed, and he transforms from a savior into a fugitive hunter. His arc is a profound struggle with his own morality. He is forced to learn skills far removed from medicine, such as marksmanship, as he grapples with the idea of taking a life to save others. Despite the immense psychological toll and being pushed to the brink of becoming a killer, Tenma ultimately holds onto his core principle, saving Johan's life once again in the finale. He ends his journey free from legal blame but forever changed by the darkness he witnessed, having stared into the abyss without letting it consume him completely.

Johan Liebert

Nozomu Sasaki

Motivation

Johan is motivated by a profound nihilism born from his traumatic childhood. He believes life has no inherent meaning and seeks to demonstrate this by manipulating people into revealing the "monster" within themselves. His ultimate motivation is to achieve true non-existence, to be the nameless monster from the storybook, by killing everyone who knows of him and then dying himself, preferably at the hands of the man who saved him, Dr. Tenma.

Character Arc

Johan is the series' central enigma. As a child, he appears innocent, but after being saved by Tenma, he reveals himself as a being of immense intellect and charisma, completely devoid of empathy. His arc is not one of development but of revelation. The series slowly peels back the layers of his past, revealing the horrific experiments at Kinderheim 511 and the Red Rose Mansion that shaped him. His goal is nihilistic: to prove that life is meaningless and to orchestrate his "perfect suicide," erasing every trace of his existence. He remains a cold, manipulative force throughout, a tragic product of a cruel system who seeks to drag the world into his own emptiness. His fate is left ambiguous, questioning whether the monster was ever truly vanquished.

Nina Fortner (Anna Liebert)

Mamiko Noto

Motivation

Nina's motivation shifts throughout the series. Initially, it is pure survival and a quest for revenge against the brother who destroyed her adoptive family. This evolves into a desperate need to understand her past and the origins of the "monster." Ultimately, her goal becomes to stop Johan not by killing him, but by understanding and forgiving him, hoping to end the cycle of hatred and trauma.

Character Arc

Nina begins the story as a happy, well-adjusted law student with no memory of her traumatic past as Anna Liebert. When Johan re-enters her life, her world collapses. Her arc is a journey of rediscovery and confrontation. She hunts Johan not just for revenge, but to understand her own past and what happened to them as children. Initially intent on killing her brother, she evolves, ultimately choosing forgiveness over vengeance. She grapples with the same darkness that spawned Johan but chooses a different path, one of love and facing the future. By the end, she has reclaimed her identity and found a measure of peace, choosing to live despite the horrors she's endured.

Inspector Heinrich Lunge

Tsutomu Isobe

Motivation

Lunge's primary motivation is an obsessive, almost inhuman, dedication to his work and his belief in his own deductive perfection. He views solving the case as a purely logical puzzle and cannot fathom a criminal who leaves no trace, leading him to fixate on Tenma. His motivation eventually shifts to uncovering the truth, even if it means admitting he was wrong for years.

Character Arc

Inspector Lunge is a brilliant but emotionally detached BKA detective who becomes singularly obsessed with proving Tenma's guilt. He is introduced as an antagonist to Tenma, a seemingly infallible investigator who sacrifices his family life for his work. His character arc is one of profound humility and change. For most of the series, he refuses to believe in the existence of a man as untraceable as Johan. However, as the evidence becomes undeniable, Lunge is forced to confront his own fallibility. He eventually admits his mistake to Tenma and becomes a crucial ally in the final confrontation, having learned the importance of human connection and acknowledging a reality beyond his rigid logic.

Symbols & Motifs

The Nameless Monster (Storybook)

This recurring Czech children's story symbolizes the core of Johan's nihilistic philosophy and origin. It tells of a monster who splits in two, one going east and one west, consuming people to steal their names and identities but never feeling whole. It represents the loss of self, the corrupting nature of desire, and the idea that true horror comes from a lack of identity and love. Johan sees himself in this story, believing he is the monster who was never given a name.

The storybook appears multiple times, first discovered by Tenma during his investigation. It was written by Franz Bonaparta, the man behind the psychological experiments that created Johan. Its chilling refrain, "Munch-munch, chomp-chomp, gobble-gobble, gulp," is often used to create an atmosphere of dread. Johan uses the story to manipulate others and explain his worldview, seeing it as the blueprint for his own life and tragic existence.

Pointing to the Forehead

Johan's signature gesture of calmly pointing a finger to his own forehead is a symbol of his nihilism and his challenge to fate and morality. It is an invitation to be killed, a sign that he places no value on his own life and dares others to end it. It signifies his desire for his "perfect suicide" and his attempt to corrupt others, particularly Tenma, by forcing them into the role of a killer.

This gesture is seen at pivotal moments. He first does it as a child when Tenma saves him. He repeats it during his confrontation with Tenma in the university library and again in the final standoff in Ruhenheim. The gesture is a chilling and iconic visual that encapsulates his entire philosophy of life's meaninglessness and his deep-seated death wish.

Empty Bed

The image of an empty hospital bed symbolizes Johan's ephemeral, ghost-like nature and the ambiguity of his fate. It represents the central question of whether the "monster" can ever truly be contained or if it has once again vanished into the world. It is a metaphor for disappearance and the cyclical nature of the story, leaving the conclusion open to interpretation.

This symbol appears twice. The first time is after Tenma saves the young Johan, who then disappears from the hospital after murdering the director, beginning Tenma's nightmare. The second is in the final shot of the series, where Tenma visits a comatose Johan, only to turn back and find the bed empty, mirroring the beginning and leaving the audience to ponder if Johan has escaped or if the monster has finally ceased to exist.

Memorable Quotes

Doctor Tenma, for you all lives are created equal, that's why I came back to life. But you've finally come to realize it now, haven't you? Only one thing is equal for all, and that is death.

— Johan Liebert

Context:

Johan says this to Tenma during their first reunion in years, after Johan has just murdered a patient in front of the doctor. This is the moment Tenma realizes the horrifying consequences of his past decision. It occurs in Episode 4, "Night of the Execution".

Meaning:

This quote encapsulates the central philosophical conflict of the series. It is Johan's direct refutation of Tenma's core belief. Johan twists Tenma's act of humanitarianism into the cause of all subsequent suffering, arguing that the ultimate equalizer isn't the value of life, but the finality of death.

The only thing that's equal for all... is death.

— Johan Liebert

Context:

This is a recurring sentiment for Johan. A notable instance is spoken by Eva Heinemann in a moment of despair, reflecting Johan's philosophy that has begun to poison the world around him, highlighting the emptiness of her material wealth in the face of fear and mortality.

Meaning:

A concise and chilling summary of Johan's nihilistic worldview. It dismisses all notions of equality in life—justice, opportunity, worth—and reduces existence to a single, inevitable endpoint. This belief justifies his amoral actions, as he perceives life itself as meaningless.

How weak the mind is when it wants to forget. Maybe you didn't forget. Maybe you're lying. Is it a lie you tell everyone around you, or perhaps a lie you tell yourself?

— Johan Liebert

Context:

Johan often uses this psychological tactic on various characters to break them down. It speaks to the themes of repressed memory that are central to Nina's character arc and the secrets held by many people Tenma encounters on his journey.

Meaning:

This quote reveals Johan's deep understanding of human psychology and his ability to manipulate people by exploiting their deepest fears and self-deceptions. He targets the fragile nature of memory and the lies people tell themselves to cope with trauma, using it as a weapon to destabilize his victims.

Munch-munch, chomp-chomp, gobble-gobble, gulp.

— Narrator of "The Nameless Monster"

Context:

This line is repeated whenever the story of "The Nameless Monster" is told, most chillingly when heard on a recording from Johan's childhood. It becomes an auditory motif for the horror at the heart of the series.

Meaning:

This phrase, from the storybook that shaped Johan's psyche, is a childish yet terrifying representation of consumption and the destruction of identity. The monster eats people to steal their names and stories, symbolizing Johan's own void of self and his parasitic effect on the lives of others.

Don't just follow orders! You're men, not machines! In your hearts, you know what's right, the answer is sitting there, waiting for you. Are you brave enough to look inside yourselves?

— Wolfgang Grimmer

Context:

Wolfgang Grimmer shouts this in a moment of crisis, trying to stop people from succumbing to paranoia and violence. It is a defining moment for his character, showcasing his inner strength despite his traumatic past. This occurs during the Ruhenheim arc, near the end of the series.

Meaning:

This is a powerful statement about individuality and morality, delivered by a man who was psychologically conditioned in Kinderheim 511 to suppress his own emotions. It's a plea for humanity against blind obedience and a testament to Grimmer's own struggle to reclaim his feelings and do what is right.

Episode Highlights

Night of the Execution

Years after saving his life, Dr. Tenma confronts a grown-up Johan Liebert for the first time. In a shocking and pivotal scene, Johan casually murders a patient Tenma was investigating and reveals himself as the architect of the hospital murders that paradoxically saved Tenma's career. This is the moment Tenma's quest officially begins, as he realizes the true nature of the "monster" he saved.

This episode is the inciting incident for the entire 70-episode chase that follows. It transforms the series from a hospital drama into a dark, psychological thriller and establishes the profound guilt that will drive Tenma for the rest of the story.

511 Kinderheim

Tenma's investigation leads him to the ruins of Kinderheim 511, a notorious East German orphanage. Through interviews with a journalist and a former staff member, Tenma learns about the brutal psychological experiments conducted there to create perfect soldiers, providing the first concrete clues about the origins of Johan's evil. He also meets Dieter, a young boy who becomes his companion.

This episode is a major turning point in the lore of the series. It expands the scope of the mystery from a single killer to a vast, state-sponsored conspiracy and introduces the theme of systematic child abuse as the source of monstrosity. It marks the beginning of understanding, rather than just chasing, Johan.

A Nameless Monster

While investigating in Prague, Tenma and Nina discover the haunting Czech storybook, "The Nameless Monster." The episode narrates the fairy tale in full, drawing chilling parallels between the monster in the book and Johan's life and philosophy. The story provides a crucial symbolic key to understanding Johan's motivations and his lack of identity.

This episode is thematically crucial, providing the central metaphor for the entire series. It explains the origin of the show's title and gives the audience a profound insight into Johan's nihilistic worldview and the psychological void at his core.

The Cruelest Thing

Considered one of the most disturbing episodes, it shows Johan (disguised as his sister, Anna) manipulating a young, vulnerable boy named Milos. Johan psychologically tortures the boy with nihilistic ideas about life's meaninglessness and the concept of being an unwanted child, mirroring his own trauma. The episode is a masterclass in psychological horror, showing Johan's evil at its most insidious.

This episode provides a raw, unfiltered look at Johan's methods. It demonstrates how he destroys people not through violence, but by dismantling their spirit and hope. It is a powerful exploration of the theme of corrupting innocence and is frequently cited by fans as one of the series' most impactful and terrifying episodes.

The Wrath of the Magnificent Steiner

A fan-favorite episode focusing on Wolfgang Grimmer. As the town of Ruhenheim descends into chaos, Grimmer, a man conditioned to be unable to feel strong emotions, finally unleashes a lifetime of repressed rage to protect a child. His heroic and tragic actions showcase his alternate persona, "The Magnificent Steiner," culminating in a deeply emotional climax where he finally experiences true feeling in his dying moments.

This episode is the culmination of Wolfgang Grimmer's character arc, one of the most beloved in the series. It serves as a powerful counterpoint to Johan, showing that even a person broken by the same system can find humanity and sacrifice themselves for good.

Scenery for a Doomsday

The penultimate episode features the final confrontation between Tenma and Johan in the rain-soaked, chaotic town of Ruhenheim. Johan, having orchestrated the town's massacre, presents Tenma with the ultimate choice: shoot him and become a murderer, or let him live. The standoff is a tense culmination of their nine-year cat-and-mouse game, a battle of ideologies fought amidst the "doomsday scenery" Johan always envisioned.

This episode brings the central conflict of the series to its climax. It is the final test of Tenma's morality and the ultimate expression of Johan's nihilistic death wish. The resolution of this standoff sets the stage for the finale.

The Real Monster

In the series finale, Tenma once again saves Johan's life after he is shot. The narrative then jumps forward, showing Tenma cleared of all charges. He visits a comatose Johan and reveals what he learned about their mother, prompting a final, ambiguous vision where Johan questions which child was truly unwanted. The series ends with a shot of Johan's empty hospital bed, leaving his ultimate fate a mystery.

The finale provides closure to Tenma's journey while intentionally leaving the central mystery of Johan open-ended. It reinforces the series' core themes of moral ambiguity and the cyclical nature of the story, solidifying its legacy as a thought-provoking thriller that trusts its audience to interpret its meaning.

Philosophical Questions

Are all lives truly equal?

This is the central question that ignites the entire plot. Dr. Tenma's unwavering belief in this principle leads him to save Johan, a decision with catastrophic consequences. The series relentlessly tests this ideal. Is the life of a charismatic sociopath who causes immense suffering equal to the lives of his innocent victims? Johan's philosophy acts as the direct antithesis, stating that only death is an equalizer. Tenma's journey is a painful exploration of this dilemma, and while he is pushed to the brink of abandoning his belief, he ultimately reaffirms it by saving Johan again, suggesting that to abandon this principle is to become a monster oneself.

What is the origin of evil: nature or nurture?

"Monster" serves as an extended case study on this debate. Johan is presented as the embodiment of evil, but the series meticulously uncovers his past in institutions like Kinderheim 511, where he was subjected to intense psychological abuse and conditioning. This suggests that his monstrosity was not innate but created. However, the story also plays with the idea that something was inherently different about Johan, which allowed the conditioning to take root so profoundly. Characters like Wolfgang Grimmer went through similar trauma but chose a path of empathy, complicating a simple "nurture" argument. The series ultimately leans towards nurture, arguing that monsters are made, not born, from a lack of love and an abundance of trauma.

Can one fight a monster without becoming one?

This question defines Tenma's internal conflict. To stop Johan, he must abandon his life-saving oath and learn to kill. His journey into the underworld, his association with criminals, and his single-minded pursuit of Johan all push him closer to the darkness he is fighting. The narrative constantly asks if taking Johan's life, even to save countless others, would be a victory or a final corruption of Tenma's soul. Johan actively tries to force Tenma into this position, believing it would be the ultimate proof of his nihilistic worldview. Tenma's refusal to kill Johan in the end is his ultimate victory, preserving his own humanity.

Alternative Interpretations

The ending of "Monster" is famously ambiguous and has generated significant discussion and multiple interpretations among fans and critics. The final shot of Johan's empty hospital bed is the primary source of this debate.

- The Literal Escape: The most straightforward interpretation is that Johan, after hearing from Tenma that his mother remembered and named him, regained consciousness and simply escaped to start a new life. The ruffled sheets indicate a recent departure. In this view, having found his identity and a semblance of being wanted, the "monster" within him has died, and he no longer has a reason to cause destruction.

- The Metaphorical Disappearance: Another popular theory is that the empty bed is purely symbolic. Inspector Lunge once noted that a true monster leaves no trace. The disturbed bedsheets are a trace, meaning Johan is no longer a monster. He may still be physically in a coma in the bed, but the metaphorical "Monster" has vanished. Tenma's conversation with him was a hallucination or a dream, a way for Tenma to find his own closure.

- The Cyclical Horror: A darker interpretation suggests that Johan has indeed escaped and the cycle is destined to repeat. The world is not safe, and the monster is once again free. The ambiguous ending serves as a final, unsettling piece of horror, implying that such evil can never be truly contained.

- The Mother as the "Real Monster": The finale heavily implies that the true monster might have been the mother who was forced to give one of her children away for the experiment. Johan's final question—"Was it me or Nina she didn't need?"—suggests that the act of being made to feel unwanted was the traumatic origin point of his monstrosity. His disappearance could be seen as his final act of becoming truly nameless and non-existent, having confronted the source of his pain.

Cultural Impact

"Monster" is widely regarded as a masterpiece of the psychological thriller genre in both manga and anime. Created by Naoki Urasawa, one of the most respected manga artists of his generation, the series first gained acclaim for its complex, cinematic storytelling and mature themes when the manga was serialized from 1994 to 2001. Set against the backdrop of post-Cold War Europe, it tapped into the anxieties of a newly reunified Germany, exploring the lingering shadows of Soviet and Nazi-era ideologies, particularly the ethical horrors of eugenics and psychological conditioning.

The 2004 anime adaptation by Madhouse brought the story to a wider international audience and was praised for its remarkable fidelity to the source material. Unlike many anime of its time, "Monster" featured a realistic art style, a grounded, real-world setting, and a slow-burn pace that favored character development and suspense over action. It has been critically acclaimed for its intricate plot, philosophical depth, and its creation of one of anime's most iconic villains, Johan Liebert. Though perhaps not as commercially mainstream as series like "Death Note," "Monster" has achieved a near-mythical status among critics and fans as a flawless work of fiction.

Its legacy lies in its influence on mature storytelling in anime and manga. It demonstrated that animation could be a medium for a sophisticated, novelistic thriller that tackles complex philosophical questions about morality, identity, and the human condition. The series continues to be a benchmark for psychological dramas and is frequently recommended as a must-watch for those seeking deep, character-driven narratives.

Audience Reception

"Monster" has received overwhelmingly positive reviews from both critics and audiences since its release, and it is widely regarded as a masterpiece of the psychological thriller genre. Viewers consistently praise its intricate and intelligent plot, comparing it to a complex novel that demands attention and thought. The character development is a frequently highlighted strength, particularly the compelling dynamic between the idealistic hero Dr. Tenma and the chillingly charismatic villain, Johan Liebert, who is often cited as one of the greatest antagonists in all of anime.

Common points of praise include the series' mature tone, its grounded realism, and its deep exploration of complex philosophical themes such as morality, the nature of evil, and existentialism. The slow-burn pacing, however, is a point of division. While many fans appreciate the deliberate build-up of suspense and the detailed exploration of its large cast of supporting characters, some viewers find the 74-episode length daunting and the pace occasionally too slow. The famously ambiguous ending is also a topic of debate; many laud it as thought-provoking and thematically fitting, while a minority found it underwhelming or unsatisfying, wishing for more concrete answers. Overall, "Monster" is held in extremely high esteem, considered an essential and highly intelligent anime for mature audiences.

Interesting Facts

- Creator Naoki Urasawa was reportedly hospitalized once during the manga's serialization, highlighting the intense pressure of its production schedule.

- The anime adaptation by studio Madhouse is known for being exceptionally faithful to the original manga, often recreating panels and scenes shot-for-shot.

- The title "Monster" is believed to be inspired by Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein," with Dr. Tenma as the Dr. Frankenstein figure who creates a "monster" (Johan) he feels responsible for stopping.

- The character designs by Shigeru Fujita intentionally stayed very loyal to Naoki Urasawa's original distinctive art style.

- The series is set in a meticulously researched post-reunification Germany and Czech Republic, using real-world locations like Düsseldorf, Heidelberg, and Prague to ground its dark narrative in reality.

- Naoki Urasawa wrote a follow-up novel titled "Another Monster," which details the events of the series from the perspective of an investigative journalist, filling in some gaps and exploring the story's aftermath.

Easter Eggs

The characters Gustav Milch and his girlfriend, who are criminals Tenma encounters, are visually and dynamically similar to Pumpkin and Honey Bunny from Quentin Tarantino's film "Pulp Fiction."

This appears to be a stylistic homage by creator Naoki Urasawa to the iconic 1994 film, which was released around the same time the manga began its serialization. It's a subtle nod to a contemporary piece of crime fiction that shared a similar non-linear and character-focused storytelling style.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!