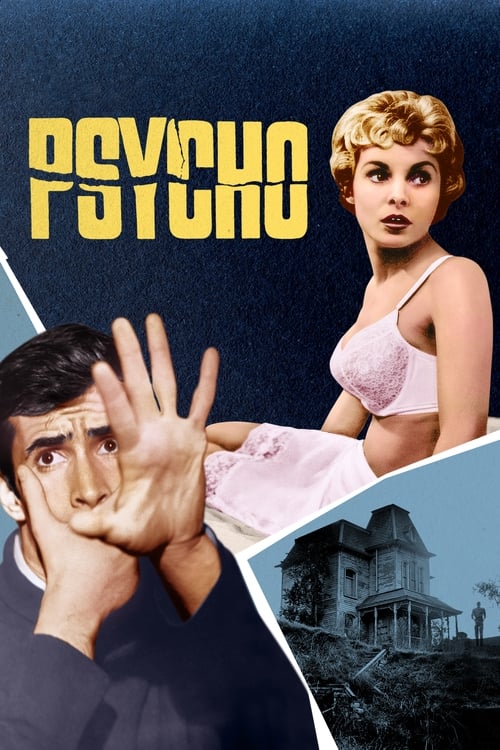

Psycho

"A new and altogether different screen excitement!"

Overview

Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho begins by following Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), a Phoenix real estate secretary who is unhappy in her love life. In a moment of impulsive desperation, she steals $40,000 in cash from her employer and flees the city, hoping to start a new life with her boyfriend, Sam Loomis (John Gavin).

Driving towards California, a heavy rainstorm forces her to take refuge for the night at the remote and eerie Bates Motel. She is greeted by the seemingly gentle but peculiar proprietor, Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), who lives in a foreboding Gothic house on a hill overlooking the motel, supposedly with his invalid, domineering mother. Their conversation reveals unsettling details about Norman's isolated life and his complex relationship with his mother, setting a tone of deep unease.

Marion's disappearance prompts her concerned sister, Lila (Vera Miles), and Sam to investigate. They are soon joined by a tenacious private investigator, Milton Arbogast (Martin Balsam), who is hired to recover the stolen money. Their search leads them to the Bates Motel, where they begin to unravel the disturbing secrets hidden within its walls and the dark truth about Norman and his mother.

Core Meaning

The core meaning of Psycho delves into the duality of human nature and the dark, often repressed, psychological forces that lie beneath a civilized exterior. Director Alfred Hitchcock masterfully suggests that everyone is capable of madness and transgression, blurring the lines between good and evil, sanity and insanity. The film explores how guilt, sexual repression, and fractured identity can lead to horrific consequences. It serves as a chilling commentary on the hidden darkness within ordinary people and the terrifying idea that the monster is not a creature from science fiction, but the person next door.

Thematic DNA

The Duality of Human Nature

Psycho is built on the theme of duality. This is most evident in Norman Bates, who has a split personality, embodying both himself and his 'Mother'. However, this theme also applies to Marion Crane, who transitions from a seemingly ordinary secretary to a thief. Hitchcock visually represents this through motifs like mirrors, which frequently appear to show characters' divided selves, and the use of black and white, particularly in Marion's choice of undergarments which change from white to black after she steals the money.

Voyeurism and Surveillance

The film opens with the camera moving into a hotel room window, immediately positioning the audience as voyeurs. This theme is central to the narrative, most notably when Norman spies on Marion through a peephole hidden behind a painting. The recurring motif of eyes—from the blank stares of Norman's taxidermy birds to the lingering close-up on Marion's lifeless eye—reinforces the unsettling feeling of being watched, implicating the audience in the on-screen transgressions and blurring the line between observer and participant.

Guilt and Atonement

Marion Crane's journey is driven by her guilt over stealing the money. Her decision to take a shower just before her murder is often interpreted as a symbolic act of cleansing, an attempt to wash away her sins and start anew. Norman's psychosis is also rooted in a profound, albeit twisted, sense of guilt over committing matricide, leading him to resurrect his mother within his own mind to escape the unbearable truth of his actions.

The Corruption of Innocence

Psycho systematically deconstructs notions of American innocence and the safety of the traditional family unit. The film presents a world where ordinary people commit crimes and where the seemingly harmless 'boy next door' is a deeply disturbed murderer. The mother-son relationship, typically a symbol of nurturing and safety, is twisted into a source of psychosis and horror, suggesting that deep-seated evil can fester in the most unexpected places.

Character Analysis

Norman Bates

Anthony Perkins

Motivation

Norman's primary motivation is rooted in a deeply pathological and Oedipal attachment to his mother. After murdering her and her lover out of jealousy, he develops a second personality ('Mother') to escape the guilt. This 'Mother' personality is murderously jealous and emerges to kill any woman to whom Norman feels attracted, thereby preventing him from having relationships with other women and preserving his twisted loyalty to his mother.

Character Arc

Norman Bates initially appears as a shy, gentle, and sympathetic motel proprietor, seemingly trapped by his domineering mother. As the film progresses, his polite but awkward demeanor gives way to moments of defensive intensity, revealing a deeply troubled individual. His arc is one of revelation rather than change; the audience discovers that his seemingly separate, abusive 'Mother' is a violent alternate personality he developed after murdering the real Norma Bates years ago. By the end, the 'Mother' personality has completely taken over, erasing what was left of Norman.

Marion Crane

Janet Leigh

Motivation

Marion is motivated by a desperate desire to escape her circumstances and build a legitimate life with her debt-ridden boyfriend, Sam Loomis. The stolen money represents a shortcut to the happiness and stability she craves, a way to 'buy off' her unhappiness, but this impulsive act only leads her down a path of fear and, ultimately, to her demise.

Character Arc

Marion begins as a relatable but frustrated woman, trapped in a dead-end affair and longing for a better life. In a moment of desperation, she breaks from her conventional life by stealing $40,000, becoming a fugitive consumed by paranoia and guilt. Her conversation with Norman Bates at the motel serves as a moment of introspection, leading her to decide to return the money and atone for her crime. Her arc is tragically cut short when she is murdered, subverting audience expectations that she is the film's protagonist.

Lila Crane

Vera Miles

Motivation

Lila's motivation is straightforward and unwavering: to find her missing sister, Marion. When she learns of the stolen money, her quest expands to understanding the full scope of what happened. Her love and concern for her sister fuel her persistence, pushing her to take risks that others would not.

Character Arc

Lila is introduced after Marion's disappearance as a determined and resourceful woman. Her arc is that of an investigator, driven to find the truth about her sister's whereabouts. Unlike Marion, she is pragmatic and resilient. She bravely confronts Norman and ventures into the Bates house, ultimately being the one to uncover the horrific truth in the fruit cellar. Her survival and role in bringing down the killer establish her as a prototype for the 'Final Girl' trope in horror films.

Sam Loomis

John Gavin

Motivation

Sam's initial motivation is to maintain his relationship with Marion despite his financial difficulties. After she disappears, his motivation shifts to finding her and, later, to protecting her sister, Lila. He feels a degree of responsibility and guilt, which drives him to help solve the mystery at the Bates Motel.

Character Arc

Sam starts as the source of Marion's frustration; his debts are the primary obstacle to their marriage. Initially, he is somewhat passive and unaware of the true danger. However, galvanized by Lila's determination and the disappearance of the investigator Arbogast, he becomes an active participant in the search. His arc sees him move from a distant lover to a protective figure who ultimately saves Lila by subduing Norman in the film's climax.

Symbols & Motifs

Birds

Birds symbolize predatory nature, entrapment, and the dual aspects of Norman's personality. Norman's hobby is taxidermy, specifically stuffing birds, which mirrors his act of preserving his mother's corpse. The birds in the parlor, particularly the owl with its wings spread, appear menacing and watch over the scene like silent judges. Furthermore, bird-related language is used throughout: Marion's last name is Crane, she is from Phoenix, and Norman remarks that she eats like a bird.

The stuffed birds are prominently displayed in the motel parlor during Norman and Marion's conversation. They loom over the characters, creating a threatening atmosphere. Norman compares Marion to a bird, and his dialogue often hints at themes of being trapped, much like his preserved specimens.

Mirrors and Reflections

Mirrors and reflections are used extensively to symbolize the theme of duality and fractured identity. They reflect the characters' inner conflicts and hidden selves. For Marion, her reflection signifies her guilt and her split from her former moral self. For Norman, reflections hint at his fragmented psyche, where two personalities exist in one body.

Hitchcock repeatedly frames characters with their reflections. Marion is seen with her reflection in the hotel room with Sam, at home, and in the bathroom of the car dealership after stealing the money, though she avoids looking at it. The film ends with a shot of Norman's face superimposed with the skull of his mother, the ultimate visual representation of his dual identity.

The Bates House

The Gothic, ominous house overlooking the modern, horizontal motel represents the dominance of Norman's 'Mother' personality over his own. Its verticality contrasts sharply with the low-lying motel, symbolizing the conscious (motel) and the unconscious, repressed mind (house). It is a physical manifestation of Norman's fractured psyche, with the dark secrets literally kept in the upper floors and the fruit cellar.

The house is constantly seen looming in the background behind the motel. Characters who venture into the house, such as Arbogast and Lila, are confronting the source of the mystery and danger. The final revelation of Mrs. Bates's mummified corpse occurs in the fruit cellar, the deepest and darkest part of the house and, symbolically, of Norman's mind.

Water and Rain

Water, particularly in the form of the downpour and the shower, symbolizes purification, cleansing, and ultimately, punishment. The torrential rain forces Marion off the main road and into Norman's trap. Her decision to shower is an attempt to wash away her guilt before she is brutally punished for her crime. Finally, her car and the stolen money are sunk into a swamp, with water being the final resting place for her and her transgression.

A heavy rainstorm begins as Marion is on the run, obscuring her vision and leading her to the Bates Motel. The shower scene is the film's most iconic use of water, transforming a symbol of cleansing into a site of horrific violence. The film's conclusion involves Norman sinking Marion's car into the swampy water behind the motel.

Memorable Quotes

A boy's best friend is his mother.

— Norman Bates

Context:

Norman says this to Marion Crane in the motel parlor during their dinner. Marion has just suggested that he should perhaps put his difficult mother in an institution, which Norman defensively rejects. The line serves as a stark warning about his priorities and the unbreakable (and unnatural) bond he shares with 'Mother'.

Meaning:

This iconic line, delivered with a chilling sincerity by Norman, encapsulates the core of his psychosis. On the surface, it sounds sweet and devoted, but in the context of the film, it reveals the deeply unhealthy, Oedipal nature of his relationship with his mother, which is the root of all the horror. It's a perfect example of Hitchcock's use of dialogue to create dramatic irony and foreshadow the terrifying truth.

We all go a little mad sometimes.

— Norman Bates

Context:

During his conversation with Marion in the parlor, Norman is explaining why he tolerates his mother's difficult behavior. He follows up his statement that his mother 'just goes a little mad sometimes' with this line, directly asking Marion 'Haven't you?', to which she agrees.

Meaning:

This quote serves as one of the central themes of the film. Norman says it to normalize his mother's strange behavior, but it also implicates Marion, who has just committed a desperate, 'mad' act of theft. The line brilliantly blurs the boundary between sanity and insanity, suggesting that the potential for madness exists within everyone, not just the overtly disturbed. It makes Norman's character more complex and unsettlingly relatable at that moment.

She wouldn't even harm a fly.

— Norman Bates (as 'Mother')

Context:

The line is heard in a voiceover as we see Norman Bates sitting in a cell at the police station, wrapped in a blanket. A fly lands on his hand, and he doesn't move. The monologue reveals 'Mother's' thoughts, blaming Norman and asserting her own innocence to the authorities she imagines are watching her.

Meaning:

This is the final line of the film, delivered as an internal monologue from the 'Mother' personality, which has now completely taken over Norman's mind. The phrase is dripping with dramatic irony, as the audience knows 'Mother' is a brutal murderer. It highlights the complete psychotic break and the chilling delusion of the character, ending the film on a deeply unsettling note by showcasing the 'Mother's' feigned innocence.

They'll see, and they'll know, and they'll say, 'Why, she wouldn't even harm a fly.'

— Norman Bates (as 'Mother')

Context:

This is part of the final internal monologue from the 'Mother' personality while Norman is in police custody. He is sitting placidly, and the voiceover reveals 'Mother's' intention to appear harmless to convince everyone of her innocence while implicating her son.

Meaning:

This quote, from the film's final moments, reveals the depth of Norman's psychosis. The 'Mother' persona has completely subsumed his own, and she is now performing innocence for an imagined audience. The line is chilling because it demonstrates a cunning awareness mixed with complete delusion. The fly on Norman's hand becomes a prop in this mental performance, a final, horrifying symbol of his transformed state.

Philosophical Questions

What is the nature of evil and madness?

Psycho challenges the idea of evil as a purely external force. Instead, it presents evil as a product of internal psychological decay. The film asks whether Norman Bates is inherently evil or a victim of his abusive upbringing and subsequent mental illness. The psychiatrist's explanation at the end attempts to logically categorize Norman's madness as Dissociative Identity Disorder, suggesting a scientific, rather than moral, failing. However, the final shot of Norman, with 'Mother's' personality in full control, leaves the audience with a chilling sense of pure, inexplicable evil, questioning whether madness can ever be fully understood or contained.

Are the lines between sanity and insanity clearly defined?

The film deliberately blurs the lines between what is considered sane and insane behavior. Norman's famous line, 'We all go a little mad sometimes,' is directed at Marion, who has just committed a crime out of desperation. This suggests a continuum of 'madness' rather than a strict binary. While Norman's condition is extreme, Marion's transgression shows how an ordinary person can be driven to an irrational act by societal pressures. The film forces the audience to confront the unsettling idea that the potential for psychological breakdown exists within everyone, hidden just beneath the surface of a seemingly normal life.

Alternative Interpretations

While the film's primary reading focuses on Norman's psychosis, Psycho has been subject to numerous alternative interpretations, particularly through psychoanalytic and feminist lenses.

A Psychoanalytic Reading: This perspective views the entire film as a complex Freudian drama. Norman's condition is seen as a textbook Oedipus complex gone horrifically wrong. His inability to resolve his infantile attachment to his mother and his jealousy towards her lover leads to matricide. Subsequently, he creates the 'Mother' persona, not just out of guilt, but as a defense mechanism to repress his own sexual desires, which he has been taught are sinful. The Bates house itself can be interpreted as a map of the human psyche: the main floor representing the ego (Norman's conscious self), the top floor representing the superego (the domineering 'Mother'), and the fruit cellar representing the id (repressed secrets and primal urges).

A Feminist Reading: Some feminist critics interpret Psycho as a commentary on female punishment in a patriarchal society. Marion Crane is initially presented as a transgressive woman; she is engaged in a pre-marital affair and steals money to control her own destiny. In this reading, her brutal murder in the shower, a moment of vulnerability and cleansing, is seen as a symbolic and violent punishment for defying societal norms. The film's second half then shifts to a more conventional, less threatening female figure, Lila, who is less independent and ultimately needs to be saved by a man (Sam). From this perspective, the film reinforces traditional gender roles by violently eliminating the woman who sought independence.

Cultural Impact

Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho was a watershed moment in cinematic history, profoundly altering the horror genre and filmmaking conventions. Released in 1960, a time when horror films often featured supernatural monsters or sci-fi creatures, Psycho introduced the idea that the monster could be a seemingly normal human being, shifting the locus of fear from the fantastic to the psychologically disturbed person next door. This innovation is credited with creating the template for the modern psychological thriller and giving birth to the slasher film subgenre.

The film shattered narrative conventions, most notably by killing off its protagonist, Marion Crane (played by star Janet Leigh), within the first act. This audacious move shocked audiences and critics, upending expectations and demonstrating that no character was safe. The graphic (for its time) violence and sexuality in scenes like the iconic shower murder pushed the boundaries of the then-powerful Hays Code, contributing to its eventual decline and paving the way for more explicit content in American films.

Critically, the film was initially met with mixed reviews due to its dark subject matter, but audience fascination and massive box office returns led to a swift reappraisal. It is now considered one of Hitchcock's greatest achievements and one of the most significant films ever made. Its influence is vast, seen in countless films that have borrowed its themes of psychological horror, surprise plot twists, and its iconic, tension-building score by Bernard Herrmann. The shower scene itself has become one of the most famous and parodied sequences in all of cinema, cementing its place in the cultural lexicon and ensuring that Psycho's shadow looms large over the horror landscape to this day.

Audience Reception

Upon its release in 1960, Psycho generated a polarized but intensely strong reaction from audiences and critics. Many viewers were profoundly shocked and horrified by the film's unprecedented level of violence, particularly the brutal and sudden murder of the film's apparent star, Janet Leigh. Reports from the time describe audiences screaming, fainting, and running out of theaters. This visceral reaction was precisely what Hitchcock aimed for, amplified by his innovative marketing campaign that forbade late entry to the theater to protect the plot's twists.

Initial critical reviews were mixed, with some prominent critics dismissing it as a 'sleazy horror film' and a low point for the acclaimed director, finding its subject matter distasteful. However, the public was captivated. The film was an immense commercial success, breaking box office records and proving that audiences had an appetite for this new brand of psychological horror. This overwhelming public support led to a critical re-evaluation, and the film was soon recognized for its masterful direction, suspenseful atmosphere, and groundbreaking narrative. Today, Psycho is universally hailed as a masterpiece and one of the most influential films ever made, with modern audiences and critics praising its timeless ability to thrill and disturb.

Interesting Facts

- The 'blood' in the iconic shower scene was actually Bosco brand chocolate syrup, which had a more realistic look and consistency on black-and-white film.

- Alfred Hitchcock was so determined to keep the film's twists a secret that he bought up as many copies of Robert Bloch's source novel as he could to prevent people from reading the ending.

- The film was shot in black and white not only to save money but also because Hitchcock believed it would be too gory for audiences in color.

- Paramount Pictures was reluctant to finance the film, so Hitchcock funded much of the $800,000 budget himself, using the crew from his television series 'Alfred Hitchcock Presents' to cut costs. He took 60% ownership of the film in lieu of a salary, a decision that made him a fortune.

- The screeching violin score for the shower scene, composed by Bernard Herrmann, is one of the most famous pieces of film music. Initially, Hitchcock wanted no music at all in the sequence, but Herrmann composed it anyway. When Hitchcock heard it, he immediately approved and later stated the score was responsible for '33% of the effect of the film'.

- Psycho was the first American film to show a flushing toilet on screen, a detail that censors initially objected to but was integral to the plot as it showed Marion trying to dispose of evidence.

- The intense shower scene, which lasts less than a minute on screen, took seven days to shoot and involved 78 different camera setups.

- The character of Norman Bates was loosely inspired by the real-life Wisconsin murderer and grave robber Ed Gein.

- To preserve the film's surprises, Hitchcock instituted a strict 'no late admissions' policy for theaters showing the film, a revolutionary practice at the time when audiences were used to entering a movie at any point.

Easter Eggs

Alfred Hitchcock's Cameo

As is his signature, director Alfred Hitchcock makes a brief appearance early in the film. He can be seen about six or seven minutes in, standing on the sidewalk outside Marion Crane's office wearing a Stetson hat as she walks back inside. Hitchcock reportedly chose to make his cameo early in the film so that audiences wouldn't be distracted looking for him throughout the rest of the story.

Painting 'Susanna and the Elders'

The painting that Norman removes from the wall to spy on Marion is a replica of a piece depicting the biblical story of 'Susanna and the Elders.' In the story, two elders spy on the virtuous Susanna as she bathes. This detail directly mirrors Norman's voyeurism and foreshadows the violation that is to come in the shower, adding a layer of classical symbolism to his transgression.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!