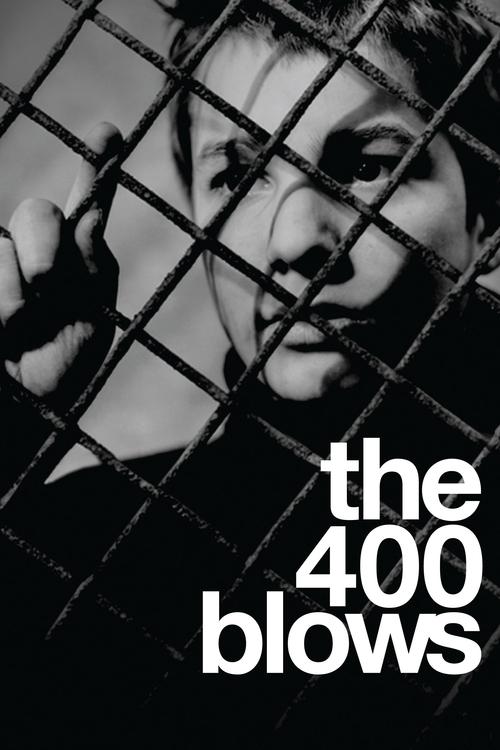

The 400 Blows

Les Quatre Cents Coups

"Angel faces hell-bent for violence."

Overview

"The 400 Blows" is the directorial debut of François Truffaut and a seminal film of the French New Wave. It introduces Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud), a misunderstood and troubled adolescent growing up in Paris. Antoine feels neglected by his distracted mother, Gilberte (Claire Maurier), and his easy-going but ineffectual stepfather, Julien (Albert Rémy). His home life is cramped and tense, and at school, he is perpetually singled out as a troublemaker by his stern teacher.

Seeking freedom and affection, Antoine frequently skips school with his best friend René, escaping into the cinemas and streets of Paris. A series of misunderstandings, lies, and petty crimes, including stealing a typewriter from his stepfather's office, leads to his escalating conflict with the adult world. His parents, feeling overwhelmed and unable to cope with his behavior, ultimately turn him over to the authorities. The film follows Antoine's journey through the impersonal juvenile justice system, culminating in his confinement in an observation center for troubled youths.

Core Meaning

The core meaning of "The 400 Blows" is a deeply personal and unsentimental exploration of the injustices and neglect faced by children in an indifferent adult world. Director François Truffaut, drawing heavily on his own troubled childhood, critiques the rigid and often cruel institutions of family and school that fail to understand or nurture a rebellious spirit. The film isn't just a character study of a delinquent; it's a powerful statement on the universal need for love, freedom, and understanding during the vulnerable transition from childhood to adulthood. Antoine's rebellion is portrayed not as malice, but as a desperate cry for the attention and affection he is denied. The film ultimately suggests that such a restrictive environment can push a sensitive child toward a path of alienation and crime, leaving them trapped with an uncertain future.

Thematic DNA

Adolescent Alienation and Rebellion

Antoine Doinel is profoundly alienated from the adult world, which he perceives as hypocritical and oppressive. His rebellion is a direct response to the neglect from his parents and the rigid discipline of his school. He lies and commits petty crimes not out of inherent malice, but as a means of survival and a way to assert his identity in a world that seems determined to crush it. His actions, like skipping school to go to the movies or running away from home, are desperate attempts to find freedom and a sense of self. The film portrays this rebellion with sympathy, suggesting it is a natural consequence of his environment.

The Failure of Authority and Institutions

"The 400 Blows" presents a scathing critique of the institutions meant to care for children. Antoine's parents are emotionally absent; his mother is resentful of his existence, and his stepfather is well-meaning but ultimately ineffectual and unwilling to take responsibility. The school system is depicted as a stifling, punitive environment where teachers like "Sourpuss" resort to humiliation rather than understanding. The juvenile justice system is shown as a cold, impersonal bureaucracy that processes children without empathy, as seen when Antoine is placed in a holding cell with adult criminals.

The Search for Freedom

A powerful undercurrent throughout the film is Antoine's relentless pursuit of freedom. This is visualized through his constant running through the streets of Paris and, most iconically, in the final extended tracking shot where he escapes the youth detention center and runs until he reaches the sea. The sea represents the ultimate, boundless freedom he has always longed for. However, the ambiguous final shot suggests that achieving this physical freedom does not resolve his internal turmoil or answer the question of what comes next.

Cinema as Refuge

Reflecting Truffaut's own life, cinema is presented as a crucial escape for Antoine. He and René often skip school to go to the movies, finding solace and a substitute home in the darkness of the theater. This theme highlights the power of art to provide comfort and inspiration for those who feel like outcasts in the real world. One scene shows Antoine stealing a lobby photo from a cinema, an act that Truffaut would later quote in his film "Day for Night."

Character Analysis

Antoine Doinel

Jean-Pierre Léaud

Motivation

Antoine is primarily motivated by a deep-seated desire for affection, recognition, and freedom from the oppressive environments of his home and school. He acts out to escape his cramped, loveless apartment and the rigid, unfair discipline he faces. He lies because he believes the truth won't be believed anyway. Ultimately, he craves the liberty to simply be himself.

Character Arc

Antoine begins as a mischievous but not malicious boy who feels misunderstood and neglected. His acts of rebellion escalate from skipping school to petty theft in a downward spiral driven by the indifference and hostility of the adults around him. Rather than being reformed by the system, he is further alienated, culminating in his escape from the youth detention center. His arc is not one of maturation in the traditional sense, but of a desperate flight towards an uncertain freedom, ending in a state of limbo.

Gilberte Doinel (The Mother)

Claire Maurier

Motivation

Gilberte is motivated by self-interest and a desire to live her own life without the encumbrance of a son she never wanted. Her actions are driven by impatience and resentment. She is more concerned with her affair and her personal freedom than with Antoine's well-being.

Character Arc

Gilberte's character remains largely static. She is portrayed as selfish, resentful, and distracted by her own desires, including an extramarital affair. It's revealed she considered having an abortion and seems to view Antoine as a burden. Her treatment of him alternates between fleeting moments of kindness (when she feels guilty) and harsh indifference. Her final act is to wash her hands of him completely, telling him at the youth center that she and his stepfather are giving up custody.

Julien Doinel (The Stepfather)

Albert Rémy

Motivation

Julien is motivated by a desire for an easy life. He enjoys the fun aspects of having a family but is unwilling to handle the responsibilities of raising a troubled child. His passion lies more with his racing club than with his family duties. When things become difficult, his motivation shifts to removing the problem—Antoine—from his life.

Character Arc

Julien is initially shown as more friendly and playful with Antoine than Gilberte is. However, his good humor is superficial. He lacks the patience and commitment to be a true father figure. As Antoine's troubles escalate, Julien's initial warmth gives way to exasperation and detachment. He is the one who ultimately takes Antoine to the police station, and by the end, he fully agrees to relinquish responsibility for the boy.

René Bigey

Patrick Auffay

Motivation

René is motivated by friendship and a shared sense of adventure and rebellion against the adult world. He supports Antoine's schemes and offers him a place to stay, acting as the only person who consistently shows him loyalty.

Character Arc

René is Antoine's steadfast best friend and partner in truancy. He comes from a wealthier but equally neglectful family. He provides Antoine with companionship and a temporary refuge when Antoine runs away from home. His arc is minimal, but he serves as a crucial source of support and solidarity for Antoine, representing the only positive, peer-level relationship in his life. His attempt to visit Antoine at the reform school, which is denied, highlights the system's cruelty.

Symbols & Motifs

The Sea

The sea symbolizes the ultimate freedom and escape that Antoine desperately craves throughout the film. It is the mythical place he has always wanted to see, representing a horizon beyond the oppressive confines of his life in Paris.

Antoine mentions wanting to see the sea, and his mother even suggests sending him to a youth center near the coast. The film's final, iconic sequence is an extended shot of Antoine running away from the detention center until he reaches the shoreline. However, upon reaching it, his expression is ambiguous, suggesting that the reality of freedom is more complex and uncertain than the dream.

Running

The act of running is a recurring motif that represents Antoine's constant state of flight and his irrepressible desire for liberation from the constraints of his family, school, and the authorities.

Antoine is frequently shown running through the streets of Paris, whether skipping school or escaping from a situation. The most significant instance is the final scene, a long tracking shot that follows his desperate run from the reform school to the sea, viscerally conveying his final bid for freedom.

The Rotor Ride

The spinning rotor ride at the funfair is a powerful visual metaphor for Antoine's journey. It symbolizes a moment of fleeting joy and ecstatic freedom, but also his struggle against the powerful forces of society that pin him down.

While playing truant, Antoine goes on a spinning ride called a "rotor." As the ride accelerates, centrifugal force pins him to the wall, and he smiles with pure joy for the first time. He tries to turn himself upside down, fighting against the force, which allegorically represents his struggle for liberation against the constrictions of his life. The ride ends, and he is returned to the real world.

The Freeze-Frame

The freeze-frame, particularly the final shot, symbolizes a moment of capture and uncertainty. It freezes Antoine in a moment of transition, caught between his oppressive past and an unknown future, breaking the fourth wall to confront the audience with his unresolved plight.

The film uses a freeze-frame twice. The first is on Antoine's mugshot after his arrest, which zooms in to show him trapped and defined by the system. The second is the famous final shot. After reaching the sea, Antoine turns and looks directly into the camera. The film freezes on his face, and the camera zooms in, leaving his fate entirely ambiguous.

Memorable Quotes

Oh, I lie now and then, I suppose. Sometimes I'd tell them the truth and they still wouldn't believe me, so I prefer to lie.

— Antoine Doinel

Context:

During an interview with a psychologist at the observation center, Antoine is asked why his parents say he is always lying. His response is delivered in a raw, direct-to-camera monologue, giving the audience a powerful insight into his psyche.

Meaning:

This line, spoken to the psychologist at the youth center, encapsulates Antoine's worldview and his justification for his dishonesty. It reveals his deep-seated feeling that the adult world is fundamentally unjust and biased against him, making lying a preferable, almost logical, defense mechanism.

Sir, it's my mother... She's just died.

— Antoine Doinel

Context:

After skipping school and being absent, Antoine's teacher demands an explanation. Panicked, Antoine invents the dramatic excuse that his mother has passed away.

Meaning:

This is Antoine's most audacious lie, a desperate attempt to excuse his truancy. It marks a significant escalation in his rebellion and leads directly to severe consequences when his mother appears at the school, very much alive and furious. The lie reflects both his creative imagination and his emotional detachment from his mother.

Your father says he doesn't care what happens to you... He said to let you know he's washed his hands of you completely.

— Gilberte Doinel

Context:

During a visit to Antoine at the youth observation center, his mother coldly informs him that they are giving him up to the state. She delivers this devastating news without emotion, highlighting her profound lack of maternal feeling.

Meaning:

This cruel statement signifies the ultimate abandonment of Antoine by his parents. It is the moment where parental neglect officially becomes a complete relinquishment of responsibility. It confirms Antoine's deepest fears of being unwanted and cements his status as an outcast.

Therefore you hope for 500. Therefore you need 300. Here's 100.

— Julien Doinel

Context:

At the beginning of the film, Antoine asks his stepfather for 1,000 francs for lunch. Julien deconstructs the request with cynical logic before giving him a fraction of what he says he needs.

Meaning:

This exchange demonstrates Julien's superficially playful but ultimately dismissive and untrusting attitude towards Antoine. While framed as a joke, it shows that he views his stepson as inherently deceitful and punishes him for it, contributing to the cycle of mistrust between them.

Philosophical Questions

Is rebellion a product of nature or nurture?

The film compellingly argues for nurture. Antoine is not presented as an inherently "bad" child. His delinquency is a direct consequence of his environment: the emotional neglect of his parents and the oppressive rigidity of his school. The film asks us to consider whether society creates its own delinquents by failing to provide children with the love, understanding, and freedom they need to thrive. Antoine's actions are a reaction to his circumstances, a desperate attempt to cope with a world that has already labeled him a troublemaker.

What is the true nature of freedom?

Antoine spends the entire film searching for freedom from the physical and emotional constraints of his life. He finds fleeting moments of it in the cinema, on the streets with René, and on the rotor ride. His ultimate goal is the sea, a symbol of boundless liberty. However, when he finally reaches it, the film questions whether this physical liberation equates to true freedom. The ambiguous final shot suggests that freedom is not merely an escape from confinement but also a state of being that involves purpose and a place in the world, things Antoine has yet to find.

Can authority be just without empathy?

The film portrays a world where authority—parental, educational, and judicial—is exercised without empathy. Antoine's parents and teacher punish and discipline him without ever trying to understand the root causes of his behavior. The juvenile justice system treats him as a case file, not a person. "The 400 Blows" suggests that authority without understanding is merely oppression, and that such systems, intended to correct and reform, only succeed in further alienating and damaging the individuals they are supposed to help.

Alternative Interpretations

The Ambiguity of the Final Shot

The celebrated final shot of "The 400 Blows" has been the subject of numerous interpretations. After his long run to the sea, Antoine turns to face the camera, and the film freezes on his face. The ambiguity of his expression is key.

- A Confrontational Accusation: One interpretation is that by looking directly at the audience, Antoine is confronting us, the viewers, as representatives of the society that has failed him. His look is an accusation, questioning our complicity in a world that neglects its children.

- The Uncertainty of Freedom: Another reading focuses on the emotional state of Antoine. He has finally reached the sea, the symbol of his desired freedom, but his expression is not one of joy. This suggests a daunting realization: what now? Physical freedom has been achieved, but he is still trapped by his circumstances, with no clear future. The open sea mirrors the vast, terrifying openness of his future. The resolution is not a happy ending, but the beginning of a new, uncertain chapter.

- A Self-Reflexive Moment: From an auteurist perspective, the final shot can be seen as Truffaut himself breaking through the narrative. Antoine, Truffaut's alter ego, turns to face the creator and the audience, acknowledging the artifice of the film. It signifies the end of one part of the story—Truffaut's own childhood exorcised on film—and leaves the future open, just as Truffaut's own future as a filmmaker was beginning.

Cultural Impact

A Cornerstone of the French New Wave

"The 400 Blows" is considered a defining film of the French New Wave (Nouvelle Vague), a movement that revolutionized cinema in the late 1950s and 1960s. Coming from a background as a fiery critic for Cahiers du Cinéma, Truffaut put his theories into practice, rejecting the polished, studio-bound "tradition of quality" in French cinema. The film embodied the New Wave's ethos with its use of on-location shooting in Paris, natural lighting, a small budget, and a more spontaneous, documentary-like feel. Its focus on a personal, autobiographical story championed the idea of the caméra-stylo (camera-pen) and the director as an auteur, using film as a medium for personal expression as intimate as a novel.

Influence on Cinema

The film's technical and stylistic innovations had a profound and lasting impact. The use of long takes, the fluid handheld camerawork by Henri Decaë, and particularly the final, ambiguous freeze-frame shot were radical for their time. This final shot, where Antoine breaks the fourth wall, has been referenced and paid homage to in countless films, including "Moonlight". The film's honest and unsentimental depiction of childhood and adolescence set a new standard for coming-of-age stories, influencing generations of filmmakers, from Martin Scorsese to Richard Linklater.

Critical and Audience Reception

Upon its premiere at the 1959 Cannes Film Festival, "The 400 Blows" was a massive success, earning Truffaut the award for Best Director and wide acclaim. It was a box office hit in France, becoming Truffaut's most successful film in his home country. Critics praised its raw honesty, psychological depth, and revolutionary style. Its sympathetic, complex portrayal of a "juvenile delinquent" was a departure from typical cinematic depictions and resonated deeply with audiences. It continues to be regarded as one of the greatest films ever made.

Audience Reception

"The 400 Blows" was met with widespread acclaim from both critics and audiences upon its release and continues to be revered. Audiences were struck by the film's raw honesty and emotional power. The sympathetic and deeply human portrayal of Antoine Doinel was a key aspect of its praise; viewers connected with his struggle against an indifferent adult world. The film's visual style, particularly its depiction of Paris from a child's perspective and the iconic final sequence, was celebrated for its freshness and vitality. While it is not a film with major points of criticism, some contemporary viewers might find its pacing more deliberate than modern films. However, the overall verdict is overwhelmingly positive, with the film consistently cited as a masterpiece of world cinema and one of the most poignant coming-of-age stories ever told.

Interesting Facts

- The film is highly autobiographical, reflecting director François Truffaut's own troubled childhood, including his strained relationship with his parents, his time in a reform school, and his love for cinema as an escape.

- The film is dedicated to André Bazin, a renowned film critic and co-founder of Cahiers du Cinéma, who was a mentor and surrogate father to Truffaut. Bazin helped get Truffaut released from a military prison and supported his passion for film. He passed away just as shooting for "The 400 Blows" began.

- The French title, "Les Quatre Cents Coups," is an idiom that means "to raise hell" or "to live a wild life." The literal English translation, "The 400 Blows," was kept by the American distributor, which sometimes misled audiences into thinking the film was about corporal punishment.

- This was the first of five films in which Jean-Pierre Léaud portrayed Antoine Doinel, Truffaut's cinematic alter ego. Truffaut followed the character's life for over 20 years.

- Jean-Pierre Léaud was chosen for the lead role from a number of boys who auditioned. Truffaut was impressed by his spontaneous and rebellious energy, and some of Léaud's own life experiences were incorporated into the character's dialogue, particularly during the psychologist interview scene.

- The film's success at the 1959 Cannes Film Festival, where Truffaut won the Best Director award, helped launch the French New Wave (Nouvelle Vague) into international prominence.

- The final, iconic tracking shot of Antoine running to the sea was filmed from a helicopter.

Easter Eggs

In one scene, Antoine and his parents go to the cinema to see a film. The marquee lists Jacques Rivette's "Paris nous appartient" (Paris Belongs to Us).

This is an inside joke among the French New Wave filmmakers. Jacques Rivette was a fellow critic at Cahiers du Cinéma and a key director of the movement. At the time "The 400 Blows" was released in 1959, Rivette's film had not yet been released (it came out in 1961), making this a nod to a friend's upcoming work.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!