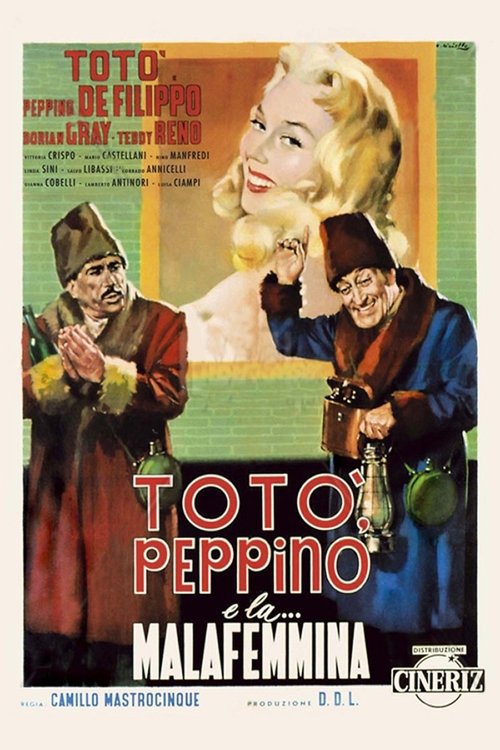

Toto, Peppino, and the Hussy

Totò, Peppino e la... malafemmina

Overview

"Toto, Peppino, and the Hussy" (Totò, Peppino e la... malafemmina) is a classic 1956 Italian comedy that tells the story of the Caponi brothers, Antonio (Totò) and Peppino (Peppino De Filippo), two simple, rural landowners from the south of Italy. Their world is turned upside down when they receive an anonymous letter informing them that their beloved nephew, Gianni (Teddy Reno), has abandoned his medical studies in Naples to follow a beautiful revue dancer, Marisa (Dorian Gray), to the northern metropolis of Milan.

Fearing Gianni has fallen for a "malafemmina" (a woman of ill repute), the well-meaning but hopelessly provincial uncles, along with their sister Lucia (Vittoria Crispo), embark on a mission to Milan to save him from supposed ruin. Their arrival in the modern, fast-paced city, for which they are comically unprepared, leads to a series of legendary gags and misunderstandings. From their absurdly heavy winter coats worn on a mild day to their disastrous attempts to communicate with the locals, their journey is a masterclass in comedic confusion.

The brothers' ultimate plan is to confront Marisa and pay her off to leave their nephew alone, a task that culminates in the iconic scene where they attempt to write a formal, intimidating letter, resulting in a hilariously garbled mess of grammar and syntax. However, as they get to know Marisa, they begin to realize that their preconceived notions about her may be entirely wrong, leading to a heartwarming and funny resolution.

Core Meaning

At its heart, the film is a comedic exploration of the cultural and social divide between the rural, traditional South and the modern, industrial North of Italy during the post-war economic boom. Director Camillo Mastrocinque uses the bumbling journey of the Caponi brothers to satirize prejudice, the clash between appearance and reality, and the anxieties of a nation undergoing rapid transformation. The core message is one of empathy and understanding, suggesting that deeply held stereotypes collapse upon genuine human interaction. The film champions the idea that family honor and love are universal values, but that judging others based on prejudice and ignorance is a recipe for absurdity and error. Ultimately, it's a celebration of overcoming biases to see the good in people, regardless of their background or profession.

Thematic DNA

North vs. South Cultural Divide

The central theme is the stark contrast between the provincial, agrarian south and the cosmopolitan, industrial north of Italy. The brothers, Antonio and Peppino, are archetypes of the Southern Italian man of the era: deeply tied to family and tradition, suspicious of the outside world, and comically out of place in a modern city like Milan. Their heavy fur coats, their misunderstanding of city life (like the fog they can't see), and their mangled attempts at formal Italian language highlight this cultural gap in a humorous but poignant way.

Appearance vs. Reality

The entire plot is driven by a misunderstanding based on appearances. The brothers assume Marisa is a "malafemmina," or a wicked woman, simply because she is a dancer in a revue. They judge her profession rather than her character. The film slowly unravels this prejudice, revealing Marisa to be a kind-hearted woman genuinely in love with Gianni. This theme critiques the rush to judgment based on stereotypes and emphasizes the importance of looking beyond superficial labels.

Family Honor and Duty

The brothers' motivation for their chaotic journey to Milan is their unwavering sense of family duty. They undertake the mission, despite their fear and ignorance of the world outside their village, to protect their nephew and uphold the family's reputation. Their actions, however misguided and absurd, stem from a place of genuine love and concern for Gianni's future, showcasing the deep-seated importance of family bonds in Italian culture.

The Comedy of Ignorance

Much of the film's humor derives from the brothers' profound ignorance. This is not presented cruelly, but as a source of endearing and relatable comedy. The pinnacle of this is the legendary letter-writing scene, where their attempt to sound authoritative and educated results in a masterpiece of grammatical nonsense. Their naivety exposes the absurdity of social pretenses and celebrates a simpler, albeit flawed, way of life.

Character Analysis

Antonio Caponi

Totò

Motivation

His primary motivation is to protect his nephew, Gianni, and uphold the Caponi family honor, which he believes has been tarnished by Gianni's association with a "malafemmina." He acts out of a deep, if misguided, sense of patriarchal duty.

Character Arc

Antonio begins as the self-proclaimed worldly-wise leader of the expedition, confidently dispensing terrible advice and leading his brother into absurd situations. He is spendthrift and often tricks money out of his stingy brother. His arc is one of gradual humbling. Through his interactions in Milan and his eventual meeting with Marisa, his rigid, prejudiced worldview softens, and he learns to see beyond his own narrow assumptions, ultimately giving his blessing to the young couple.

Peppino Caponi

Peppino De Filippo

Motivation

Peppino is motivated by a combination of fear of his brother, a genuine concern for his nephew, and an obsessive desire to protect his money from Antonio's spendthrift habits.

Character Arc

Peppino starts as the timid, stingy, and constantly put-upon younger brother, dominated by Antonio's stronger personality. While he follows Antonio's lead, he is often more fearful and skeptical. His arc involves finding a small measure of courage to question Antonio, though he remains the quintessential comedic sidekick. His transformation is less pronounced than Antonio's, but he too comes to accept Marisa, his fears assuaged by his brother's change of heart and his sister's final judgment.

Marisa Florian

Dorian Gray

Motivation

Her motivation is simple and pure: her love for Gianni. She endures the bizarre and insulting behavior of his uncles because of her commitment to him, hoping to eventually win over his family.

Character Arc

Marisa is initially presented through the prejudiced eyes of the Caponi family as a seductive, morally questionable showgirl. Her arc is about revealing her true nature. She proves herself to be a sincere, loving, and respectable woman who is genuinely in love with Gianni. She transitions from the titular "hussy" to a beloved future member of the family, leaving her career behind to marry Gianni and move to their village.

Gianni

Teddy Reno

Motivation

His motivation is his unwavering love for Marisa and his desire to make his family understand that she is a good person, worthy of their respect and acceptance.

Character Arc

Gianni is the catalyst for the plot. He starts as a dutiful student who falls head-over-heels in love. His arc is about standing up for his love against his family's prejudices. He never wavers in his devotion to Marisa. The climax of his arc is when he performs the song "Malafemmena" for Marisa, a song written by Totò himself, which helps convince his family of the sincerity and depth of their love.

Symbols & Motifs

Milan

Milan symbolizes modernity, progress, and the alienating nature of the new, post-war Italy for those left behind by the economic miracle. It is a world of fast-paced traffic, sophisticated people, and different social codes that the brothers cannot comprehend. It represents the "North" not just geographically, but as a cultural and economic force that is both alluring and intimidating.

The city is a constant source of confusion and comedy from the moment the brothers arrive. Their interactions with a Milanese traffic cop, their wandering through the Piazza del Duomo, and their general bewilderment at the city's scale and pace all serve to emphasize how out of their element they are.

The Fur Coats

The heavy, dark fur coats and hats the brothers wear upon arriving in Milan symbolize their provincialism and complete lack of worldly knowledge. They've been told the North is cold and foggy, so they dress for a Siberian winter, making them look utterly ridiculous and instantly marking them as outsiders.

This is one of the film's most iconic visual gags. They arrive at the bustling Milan train station and proceed to walk through the city, sweltering in their absurd outfits, immediately establishing their status as "cafoni" (country bumpkins) in the urban landscape.

The Letter

The letter the brothers compose is a symbol of their attempt to impose their traditional authority in a world whose language—both literal and figurative—they do not speak. The resulting gibberish symbolizes the communication breakdown between their world and Marisa's. It is a physical manifestation of their ignorance, pride, and misguided intentions.

The scene where Totò dictates the grammatically catastrophic letter to Peppino is the film's comedic centerpiece. It is an extended, brilliantly performed sequence that encapsulates the movie's core themes of ignorance and the North-South divide in a single, unforgettable moment.

Memorable Quotes

Signorina, veniamo noi con questa mia a dirvi una parola, che scusate se sono poche, ma settecentomila lire, a noi ci fanno specie che quest'anno c'è stato una grande moria delle vacche come voi ben sapete...

— Antonio Caponi (dictating the letter)

Context:

Antonio is dictating a formal letter to his brother Peppino. The letter is intended to be a stern and intimidating offer to pay off Marisa, the "malafemmina," to leave their nephew. The entire scene is a masterclass of comedic performance and writing as they argue over phrasing, punctuation, and grammar.

Meaning:

This is the opening of the iconic letter. Its convoluted, grammatically disastrous, and nonsensical phrasing is the pinnacle of the film's comedy. It perfectly captures the brothers' attempt to sound formal and educated while revealing their profound ignorance. The phrase "moria delle vacche" (death of the cows) to justify the amount of money is a classic non-sequitur that has entered the Italian cultural lexicon.

Noio volevàn savuàr l'indiriss... Pour aller à la gare...

— Antonio Caponi

Context:

Lost in Milan's Piazza del Duomo, the brothers approach a local policeman (a "ghisa"). Convinced that normal Italian won't suffice, Antonio launches into this ridiculous pseudo-French, leading to even greater confusion and cementing their status as hopelessly provincial outsiders.

Meaning:

This quote is from a famous scene where Antonio and Peppino, trying to ask for directions in Milan, decide that since it's a northern, international city, they should speak French to a traffic cop. Their "French" is an absurd, made-up gibberish based on a distorted Neapolitan accent. It hilariously demonstrates their complete alienation from the urban environment and their flawed, childlike logic.

A Milano quando c'è la nebbia non si vede! ... Ma scusi, se non si vede, come si fa a sapere che c'è la nebbia?

— Mezzacapa and Antonio Caponi

Context:

Before leaving for Milan, the brothers ask their neighbor, Mezzacapa, for advice about the city. When Mezzacapa warns them about the thick fog, Antonio responds with this baffling question, leaving his neighbor speechless and demonstrating the brothers' complete unreadiness for their journey.

Meaning:

This exchange perfectly encapsulates Totò's character's unique brand of insane, circular logic. He questions a simple statement about Milan's fog with a seemingly profound but utterly ridiculous paradox. This line highlights the clash between common knowledge and the brothers' literal, almost philosophical, interpretation of the world.

Philosophical Questions

How do preconceived notions shape our reality?

The film is a case study in how prejudice dictates perception. The Caponi brothers build an entire narrative about Marisa based on a single piece of information: her job. Their journey to Milan is a physical manifestation of their journey away from prejudice. The film explores how their "reality" of Marisa as a "malafemmina" is a complete fabrication, which hilariously and poignantly collapses when confronted with the actual person. It asks the viewer to consider how often we construct elaborate, false realities about others based on stereotypes.

Can ignorance be a form of innocence?

Antonio and Peppino are profoundly ignorant, which is the source of the film's comedy. However, the film treats their ignorance not as a moral failing but as a state of rustic innocence. Their intentions are good—they want to protect their nephew—even if their methods are absurd. The film poses the question of whether their lack of sophistication shields them from the cynicism of the modern world. Their eventual success comes not from becoming smarter, but from allowing their innate, good-hearted familial love to triumph over their learned prejudices.

Alternative Interpretations

While the film is overwhelmingly seen as a lighthearted comedy, some analysis views it through a more critical, sociological lens. One interpretation suggests that the film, beneath its humor, presents a rather melancholic portrait of the Southern Italian condition. The brothers are not just funny; they are figures of profound displacement, whose ignorance renders them powerless and ridiculous in the face of Northern modernity. Their journey can be seen as a tragicomic allegory for the internal migration of Southerners to the North, where they were often met with prejudice and condescension.

Another reading focuses on the character of Marisa. While the film's ending sees her happily abandoning her career for marriage and domesticity, a feminist interpretation might critique this as a conventional and patriarchal resolution. Marisa, an independent working woman, is ultimately "tamed" and assimilated into the traditional family structure she initially threatened. Her redemption is contingent on her renouncing her profession and conforming to the Caponi family's values, which could be seen as reinforcing the conservative social norms of the era.

Cultural Impact

"Totò, Peppino e la... malafemmina" is more than just a comedy; it is a cultural touchstone in Italy, considered a cornerstone of the Commedia all'italiana genre. Released during Italy's post-war "economic miracle," the film brilliantly captured the anxieties and absurdities of a country in rapid transition. It immortalized the cultural schism between the industrial, modern North and the agrarian, traditional South, a theme that resonated deeply with audiences and remains relevant.

The film's dialogue, particularly the letter-writing scene and the "Noio volevàn savuàr" exchange, has transcended the screen to become part of the Italian vernacular. Phrases and gags from the movie are instantly recognizable to generations of Italians and are frequently referenced in other media. The masterful comedic timing and unparalleled chemistry between Totò and Peppino De Filippo set a benchmark for cinematic comedy duos and influenced countless actors and comedians.

Initially dismissed by critics as populist fare, its enduring popularity with the public led to a critical re-evaluation over the decades. It is now celebrated as a sharp piece of social satire wrapped in a brilliantly executed farce. The film is regularly broadcast on Italian television, especially during holidays, cementing its status as a beloved classic that continues to entertain and offer a humorous yet insightful look into the Italian identity of the mid-20th century.

Audience Reception

Upon its release in 1956, "Totò, Peppino e la... malafemmina" was an immense box office success, becoming the most-watched film in Italy that year. Audiences adored the perfect comedic chemistry between Totò and Peppino De Filippo, and the film's iconic scenes, such as the letter dictation, were met with uproarious laughter and became instant classics. The public embraced the film's lighthearted satire of the North-South divide and its relatable story of family loyalty. Over the decades, its popularity has not waned; it has achieved cult status and is considered by the public to be one of the most beautiful and funny Italian films ever made. Viewers consistently praise the brilliant performances, the timeless gags, and the film's heartwarming nature, often criticizing initial reviews for failing to appreciate its comedic genius.

Interesting Facts

- The film was the highest-grossing movie in Italy for the 1956 season, earning over 1.75 billion lire.

- The iconic letter-writing scene was reportedly not in the original script and was largely improvised by Totò and Peppino De Filippo, who often embellished their scenes during filming.

- The film's title song, "Malafemmena," was a famous Neapolitan song composed by Totò himself in 1951, years before the movie was made. It adds a layer of genuine pathos to the story when sung by Teddy Reno's character.

- A young, uncredited Ettore Scola, who would later become a celebrated director, worked as an assistant director on the film and contributed to writing some of the gags.

- Despite its massive popularity with audiences, the film was initially panned by many critics of the era, who dismissed it as a crude farce and low-brow comedy. It has since been re-evaluated as a classic of the *Commedia all'italiana* genre.

- The on-screen chemistry between Totò and Peppino De Filippo was legendary, making them one of Italy's most beloved comedic duos. This film is often considered the peak of their collaboration.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!