The Battle of Algiers

La battaglia di Algeri

"The Revolt that Stirred the World!"

Overview

"The Battle of Algiers" chronicles a pivotal period in the Algerian War of Independence (1954-1962), focusing on the years 1954 to 1957. The film follows Ali La Pointe (Brahim Hadjadj), a petty criminal who becomes a key figure in the National Liberation Front (FLN) after being radicalized in prison. The narrative depicts the FLN's organized guerrilla campaign against the French colonial authorities within the city of Algiers, particularly in the labyrinthine Casbah district.

The FLN's acts of urban warfare, including assassinations and bombings, are met with an increasingly brutal response from the French government, which sends in elite paratroopers led by the methodical and ruthless Lieutenant-Colonel Mathieu (Jean Martin). The film meticulously portrays the escalating cycle of violence, where attacks and reprisals engulf both combatants and civilians. Pontecorvo's newsreel-style cinematography and use of non-professional actors lend the film a startling and immersive realism, blurring the line between historical reconstruction and documentary footage.

Core Meaning

The core message of "The Battle of Algiers" revolves around the brutal and complex nature of decolonization and the birth of a nation through armed struggle. Director Gillo Pontecorvo explores the idea that when a population is systematically oppressed, revolutionary violence becomes an inevitable, albeit tragic, political tool. The film doesn't glorify terrorism but presents it as a calculated response to the violence of colonial occupation. Furthermore, it poses a profound question about the cost of freedom and the moral compromises both sides are willing to make. The French employ systematic torture to dismantle the rebellion, while the FLN targets civilians to create terror and gain international attention. Ultimately, the film suggests that while a colonial power might win a specific battle through superior military force and brutal methods, it cannot extinguish the collective will of a people determined to be free, thus losing the larger war for independence.

Thematic DNA

Colonialism and Revolution

The film is a stark depiction of the power dynamics inherent in colonialism, showcasing the French control over Algeria and the economic and social exploitation of its people. The revolution is portrayed as a direct and violent response to this systemic oppression. The FLN's struggle is not just for political control but for the restoration of dignity and self-rule. The film details the methods of a guerrilla insurgency, from cellular organization to the use of terrorism, and the counter-insurgency tactics employed by the colonial power.

The Cycle of Violence

Pontecorvo masterfully illustrates how violence begets more violence. An FLN assassination of a police officer leads to a retaliatory bombing by French settlers, which in turn leads to the FLN bombing public places frequented by Europeans. The film maintains a neutral, observational tone, showing the devastating human cost on both sides without explicitly condemning or glorifying either. This theme highlights the tragic momentum of conflict, where each act of brutality serves as justification for the next.

The Morality of Warfare

"The Battle of Algiers" delves into the ethical gray areas of conflict. It forces the audience to confront uncomfortable questions about what actions are justifiable in the pursuit of a cause. The French paratroopers, many of whom were part of the anti-Nazi resistance, justify the use of torture as a necessary evil to dismantle the FLN and save lives. Conversely, the FLN justifies bombing civilian targets as the only way to fight back against a technologically superior occupier. The film presents these brutal acts from both sides with a chilling objectivity, leaving the moral judgment to the viewer.

Nationalism and Solidarity

The film portrays the growing sense of national identity and unity among the Algerian people. The FLN's success relies on the support and solidarity of the populace within the Casbah. This is most evident during a city-wide strike organized by the FLN to demonstrate their popular support to the United Nations. Despite the hardships imposed by the French military, the people of the Casbah largely shelter and support the revolutionaries, demonstrating a collective desire for independence that transcends individual fear.

Character Analysis

Ali La Pointe

Brahim Hadjadj

Motivation

Initially motivated by a raw sense of injustice and a desire for dignity, Ali's motivation evolves into a deep political commitment to freeing Algeria from French colonial rule. He is driven by a desire to fight back against the humiliation and brutality of the occupation and to create a self-determined future for his people.

Character Arc

Ali begins as an illiterate street criminal, boxer, and gambler, concerned primarily with his own survival. His arrest and imprisonment become a turning point after he witnesses the execution of an Algerian nationalist. Upon his release, he is recruited by the FLN. He transforms from a petty thief into a disciplined and committed revolutionary leader, embodying the radicalization of a generation of Algerians. His arc culminates in his defiant death, becoming a martyr for the cause of independence.

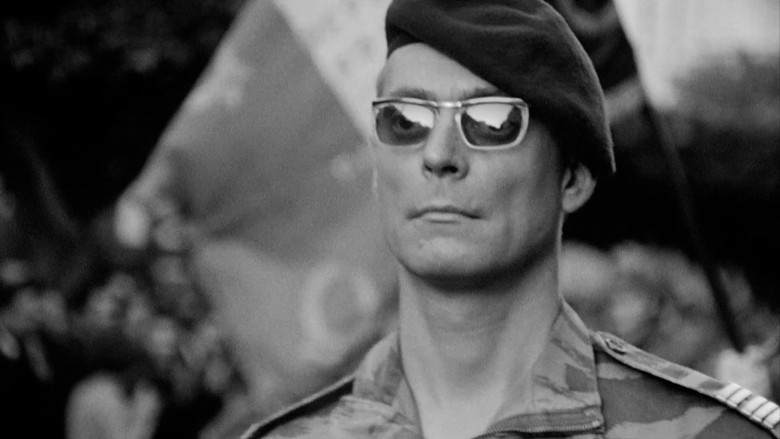

Lt. Colonel Philippe Mathieu

Jean Martin

Motivation

Mathieu is motivated by a soldier's duty to win and a belief in the necessity of maintaining French control over Algeria. He sees the conflict not in moral terms but as a tactical problem to be solved. He argues that if the political decision is to remain in Algeria, then one must accept all the "necessary consequences," including torture, to achieve that goal.

Character Arc

Colonel Mathieu does not have a traditional character arc; he arrives in Algiers as a fully formed, highly efficient counter-insurgency expert and remains so throughout the film. He is a veteran of the French Resistance and the Indochina War, which informs his ruthless pragmatism. His character serves as a personification of the cold, logical, and brutal methodology of modern warfare. He successfully achieves his military objective—destroying the FLN's leadership in Algiers—but his victory is ultimately hollow, as it fails to address the underlying political will for independence.

El-Hadi Jaffar

Yacef Saâdi

Motivation

Jaffar is motivated by a deep-seated commitment to Algerian independence. He is the strategist who understands the need for both violent action and political maneuvering. He aims to make the cost of French occupation untenable while also galvanizing the Algerian people and attracting international support for their cause.

Character Arc

As a top commander in the FLN, Jaffar (based on and played by the actual historical figure Yacef Saâdi) is the strategic mind of the revolution in Algiers. He recruits and guides Ali La Pointe, channeling his raw anger into disciplined action. His arc shows the immense pressure on the leadership of a rebellion. He orchestrates the attacks but also makes the pragmatic decision to surrender when cornered to avoid further civilian casualties, demonstrating a leader's complex responsibilities.

Symbols & Motifs

The Casbah

The Casbah, the traditional Islamic quarter of Algiers, symbolizes the heart of the Algerian identity and the soul of the resistance. It represents a space that is culturally and physically impenetrable to the French colonizers. It is the sanctuary, recruiting ground, and operational base for the FLN.

Its narrow, winding streets provide a natural advantage for guerrilla warfare, making it difficult for the French military to navigate and control. The French must invade and systematically dismantle this space to quell the rebellion, symbolizing the colonial effort to break the spirit of the Algerian people. The final siege of Ali La Pointe's hideout within the Casbah marks the tactical end of the battle but not the end of the revolutionary spirit it represents.

Women's Roles (Veils and Western Dress)

The changing attire of the female FLN members symbolizes the adaptability and strategic depth of the revolution. The traditional haik (veil) initially provides anonymity, but as checkpoints tighten, the women adopt Western clothing, makeup, and hairstyles to blend in with European settlers, turning colonial stereotypes to their advantage. This transformation signifies that the fight for liberation requires a subversion of both traditional and colonial expectations.

A pivotal sequence shows three FLN women preparing for a mission. They remove their veils, cut their hair, and apply makeup, effectively disguising themselves as modern French women. This allows them to pass through French military checkpoints with baskets containing bombs, which they then plant in civilian areas of the European quarter.

The Tapeworm Analogy

Colonel Mathieu's description of the FLN's cellular structure as a "tapeworm" symbolizes the clinical, detached, and dehumanizing perspective of the counter-insurgency effort. A tapeworm is a parasite that is difficult to eliminate completely; cutting it into pieces only creates more worms. This metaphor reveals his understanding of the enemy's structure while also framing the rebellion as a disease to be eradicated rather than a legitimate political movement to be understood.

While briefing his officers, Colonel Mathieu uses a blackboard to diagram the FLN's pyramid-like cell structure. He explains that each member only knows a few others, making it resilient. He uses the tapeworm analogy to stress that they must capture and interrogate members to trace the organization up to its "head" to destroy it completely.

Memorable Quotes

It's hard to start a revolution. Even harder to continue it. And hardest of all to win it. But, it's only afterwards, when we have won, that the true difficulties begin.

— Larbi Ben M'hidi

Context:

Spoken by the FLN leader Larbi Ben M'hidi to Ali La Pointe while discussing the strategy and immense challenges of their struggle against the French. It provides a moment of profound political reflection amidst the ongoing violence.

Meaning:

This quote encapsulates the long-term vision of the revolutionary leaders. It acknowledges that the armed struggle is only the first, difficult step. The ultimate challenge lies in building a new, stable, and just society after independence is achieved, foreshadowing the political struggles that often follow liberation movements.

Should we remain in Algeria? If you answer 'yes,' then you must accept all the necessary consequences.

— Lt. Colonel Philippe Mathieu

Context:

Colonel Mathieu poses this question to journalists at a press conference. He is defending the army's brutal methods, reframing the debate from one of morality to one of logical necessity based on a political objective.

Meaning:

This line is the cornerstone of Mathieu's chillingly pragmatic philosophy. He argues that methods like torture are not aberrations but logical and unavoidable consequences of the political decision to maintain colonial rule by force. It challenges the audience, particularly the French, to confront the true cost of their colonial project, stripping away any pretense of a purely moral high ground.

Give us your bombers, and you can have our baskets.

— An FLN Leader (in response to a journalist's question)

Context:

During a press conference scene, a captured FLN leader is asked by a French journalist whether it is cowardly to use women's baskets to carry bombs into cafes. This is his defiant and sharp-witted reply, turning the moral accusation back on the French.

Meaning:

This is a powerful retort to a journalist questioning the morality of the FLN using baskets to carry bombs that kill civilians. The quote highlights the asymmetry of the conflict. The FLN, lacking an air force or heavy artillery, resorts to the weapons available to them. It frames their 'terrorism' as the warfare of the oppressed, a direct response to the state-sanctioned violence of the colonizer's military machine.

Philosophical Questions

Is violence a legitimate tool for political liberation?

The film explores this question without offering an easy answer. It presents the FLN's use of terrorism—bombing cafes, assassinating police—as a direct response to the systemic violence and oppression of French colonialism. By showing the context from which this violence emerges, the film challenges the simple categorization of the rebels as mere criminals or terrorists. It suggests that in certain conditions of extreme inequality and repression, violence may become the only language of political expression available to the colonized.

Can a state employ immoral methods (like torture) to achieve a 'moral' objective (like order and security)?

"The Battle of Algiers" confronts this question head-on through the character of Colonel Mathieu. He argues for the necessity of torture as an efficient means of extracting information to dismantle the FLN's network and prevent further attacks. The film shows that these methods are effective in the short term, as the French do succeed in winning the 'battle' of Algiers. However, the coda, which depicts the spontaneous uprising two years later, suggests that such brutal methods ultimately delegitimize the colonial authority and galvanize the population, ensuring that the French lose the 'war'. The film forces the viewer to weigh the strategic utility of torture against its profound moral and political costs.

What is the difference between a 'terrorist' and a 'freedom fighter'?

The film deliberately blurs the line between these two labels. From the French perspective, the FLN are terrorists who indiscriminately murder civilians. From the Algerian perspective, they are patriots fighting a war of national liberation against a foreign occupier. Pontecorvo's even-handed, documentary-like approach forces the audience to see the events from both viewpoints. The film demonstrates that the labels 'terrorist' and 'freedom fighter' are often a matter of perspective, determined by which side of a conflict one is on and who ultimately holds the power to write the narrative.

Alternative Interpretations

While the film is widely seen as sympathetic to the Algerian cause, its objective, newsreel style allows for multiple interpretations. One perspective is that the film is a straightforward anti-colonialist narrative, celebrating the revolutionary spirit and inevitable victory of an oppressed people.

Another interpretation, however, focuses on the film's stark portrayal of the brutal logic of both sides, suggesting it's less a piece of propaganda and more a grim meditation on the destructive nature of political violence itself. Some viewers and critics, particularly those on the right, have seen the film as a justification of terrorism, arguing it romanticizes the FLN's methods. Conversely, some on the left have criticized it for not being radical enough, as it gives significant screen time and intellectual weight to the arguments of the French Colonel Mathieu.

A more nuanced reading suggests the film is a complex study in pragmatism. Both Ali La Pointe and Colonel Mathieu are portrayed as intelligent, dedicated, and ruthless practitioners of their respective crafts. In this view, the film is not about good versus evil, but about the clash of two opposing, and tragically irreconcilable, wills, with the outcome determined not by moral superiority but by historical inevitability and the will of the masses.

Cultural Impact

"The Battle of Algiers" had a profound and lasting cultural and political impact. Created in the immediate aftermath of the Algerian War, it was an Italian-Algerian co-production that gave an unprecedented voice to the colonized, based on the memoir of FLN leader Yacef Saâdi.

Its influence on cinema is immense. The film is a landmark of political filmmaking and a masterclass in the cinéma vérité style. Its raw, documentary-like aesthetic, achieved through black-and-white cinematography, handheld cameras, and the use of non-professional actors, has influenced countless directors seeking to create a sense of realism and immediacy. It is often associated with the Italian Neorealist movement.

The film's reception was highly controversial. In France, it was banned for five years for its unflinching depiction of French military tactics, particularly torture, which was a subject of national trauma and denial. Globally, however, it was hailed as a masterpiece, winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. For decades, it has been studied not just by film students but by insurgent groups (like the Black Panthers and the IRA) and counter-insurgency experts alike. A famous 2003 screening at the Pentagon was organized to offer insights into the challenges of urban warfare and occupation during the Iraq War, with the promotional flyer stating: "How to win a battle against terrorism and lose the war of ideas." This demonstrates the film's enduring relevance as a complex and unflinching case study of modern warfare, terrorism, and the struggle for national liberation.

Audience Reception

Upon its release, "The Battle of Algiers" was met with widespread critical acclaim internationally, winning the prestigious Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, though it was highly controversial and banned in France for years. Audiences were stunned by its realism, with many believing they were watching a genuine documentary. The film is praised for its balanced portrayal of a complex conflict, giving intellectual weight to both the Algerian revolutionaries and the French counter-insurgency forces. Viewers often highlight the film's gripping intensity and its raw, unsentimental depiction of violence, including both terrorist bombings and state-sanctioned torture. The main point of criticism, though rare among cinephiles, sometimes comes from viewers who find its neutral, observational style emotionally distant or who believe it implicitly justifies the FLN's use of terrorism. Overall, it is widely regarded by audiences and critics as one of the greatest political films ever made, with its relevance and power remaining undiminished decades later.

Interesting Facts

- The film was shot in a newsreel, documentary style, which led many viewers to believe it contained actual historical footage. However, a title card at the beginning explicitly states, "not one foot of newsreel has been used."

- The director, Gillo Pontecorvo, was a secular Jew of Italian descent and a former anti-fascist partisan, which heavily influenced his political and artistic perspective on the film.

- Most of the cast were non-professional actors. Brahim Hadjadj, who played Ali La Pointe, was an illiterate street vendor whom Pontecorvo discovered at a market.

- Yacef Saâdi, who played the FLN leader El-Hadi Jaffar, was a real-life commander of the FLN. The film is largely based on his memoir, written while he was imprisoned by the French.

- The only professional actor in a major role was Jean Martin (Colonel Mathieu). Martin had previously been dismissed from a French theater for signing a manifesto against the Algerian War.

- The film was banned in France for five years upon its release due to its politically sensitive subject matter and its portrayal of French tactics like torture.

- The film has been used as a training and instructional tool by various groups, including revolutionary organizations like the Black Panthers and the IRA, as well as by state militaries, including a notable screening at the Pentagon in 2003 to discuss the challenges of counter-insurgency in Iraq.

- It is the only film in Academy Awards history to be nominated in non-consecutive years: for Best Foreign Language Film in 1967, and for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay in 1969 after its official U.S. release.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!