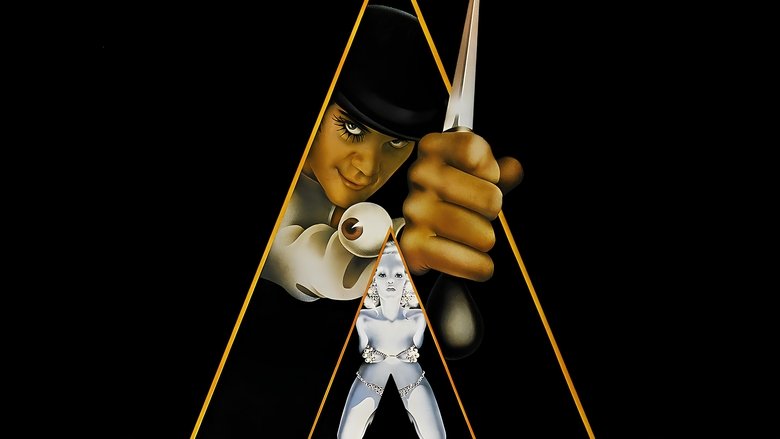

A Clockwork Orange

"Being the adventures of a young man whose principal interests are rape, ultra-violence and Beethoven."

Overview

Set in a futuristic, dystopian Britain, 'A Clockwork Orange' follows the harrowing journey of Alex DeLarge, the charismatic and sociopathic leader of a gang of 'droogs.' Alex and his friends spend their nights indulging in 'ultra-violence,' a hedonistic spree of assault, theft, and rape, all set to the soundtrack of his beloved Ludwig van Beethoven. After a home invasion goes horribly wrong, Alex is betrayed by his droogs and captured by the police.

Sentenced to a lengthy prison term, Alex volunteers for an experimental aversion therapy called the Ludovico Technique, which promises to 'cure' him of his violent tendencies in a matter of weeks. The treatment involves forcing him to watch graphic films of violence and sex, which are paired with a nausea-inducing drug. As a result, he becomes physically ill at the mere thought of violence, or even at the sound of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, which was used as a soundtrack in one of the films.

Released back into society, Alex finds himself defenseless and unable to enjoy his former passions. He is tormented by his past victims and former gang members who have since become police officers. His journey becomes a poignant exploration of whether true goodness can be imposed and if a man stripped of his free will is a man at all.

Core Meaning

The central message of 'A Clockwork Orange' is a profound exploration of the concept of free will and the nature of morality. Director Stanley Kubrick, adapting Anthony Burgess's novel, poses the question: is it better for a man to choose to be evil than to have good imposed upon him? The film critiques the idea of state-controlled rehabilitation, suggesting that by removing an individual's capacity to choose between good and evil, society creates a 'clockwork orange'—something that appears organic and natural on the outside but is merely a mechanical toy on the inside. It serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of totalitarianism and the dehumanizing potential of psychological conditioning, arguing that true humanity, with all its flaws, lies in the freedom of moral choice.

Thematic DNA

Free Will vs. Determinism

This is the most prominent theme in the film. Alex initially exercises his free will to commit heinous acts of violence. The Ludovico Technique strips him of this ability, turning him into a conditioned being who is physically incapable of violence. The prison chaplain argues that true goodness must be a conscious choice, and that a man who cannot choose ceases to be a man. The film ultimately questions whether a society that enforces good behavior at the expense of individual freedom is truly a moral one.

The Nature of Goodness and Evil

The film delves into the complexities of human nature, suggesting that the capacity for both good and evil is inherent. Alex, despite his violent tendencies, also possesses a deep appreciation for art and music, particularly Beethoven. The film challenges the audience to consider whether 'goodness' that is forced is genuine. The prison chaplain posits that evil has to exist alongside good for moral choice to be possible. Kubrick suggests that dark impulses are a fundamental part of humanity and that attempts to surgically remove them can be more dehumanizing than the evil itself.

Government Control and Manipulation

'A Clockwork Orange' is a powerful critique of a totalitarian state that will resort to any means to maintain order. The government, represented by the Minister of the Interior, is not concerned with Alex's moral salvation but rather with reducing crime statistics and freeing up prison space for political dissidents. Both the government and its opposition use Alex as a political pawn for their own ends, highlighting the manipulative nature of power.

The Interplay of Art and Life

Art, particularly classical music, plays a dual role in the film. For Alex, Beethoven's music is a source of ecstasy and inspiration for his violent acts. The Ludovico Technique then corrupts this relationship, turning his beloved music into a trigger for unbearable nausea. The film explores how art can be used to both elevate and debase the human spirit, and how life and art are inextricably linked. Alex's fascination with how the real world seems more real when viewed on a screen during his treatment also touches on themes of media and desensitization.

Character Analysis

Alex DeLarge

Malcolm McDowell

Motivation

Alex's primary motivation is the pursuit of pleasure through his own unique interests: classical music, sex, and 'ultra-violence'. He is driven by a hedonistic and anarchic impulse, a desire to assert his individuality and dominance over others. He acts because he enjoys it, as he states, 'But what I do I do because I like to do.' There is no deeper social or political motive for his initial actions; it is pure, unadulterated self-gratification.

Character Arc

Alex begins as a charismatic but deeply sociopathic gang leader who revels in 'ultra-violence' and classical music. His arc is not one of redemption, but of transformation through external forces. After his capture, he is subjected to the Ludovico Technique, which forcibly strips him of his violent impulses and free will, turning him into a helpless victim. He is then brutalized by the very society he once terrorized. In the end, his conditioning is reversed, and he exclaims, 'I was cured, all right,' implying a return to his old self, now with the state's endorsement. He goes from a perpetrator of violence to a victim of it, and finally to a symbol of the state's hypocrisy.

Mr. Frank Alexander

Patrick Magee

Motivation

Initially, his motivation is to expose the government's dehumanizing techniques. However, his overriding motivation becomes personal revenge against Alex for the assault on him and the death of his wife. He is willing to sacrifice Alex's life to achieve this vengeance and to make a political statement.

Character Arc

Mr. Alexander is first introduced as a writer and a victim of Alex's brutal home invasion, during which he is crippled and his wife is raped. He later re-emerges as a political dissident who seeks to use Alex's 'cured' state as a weapon against the incumbent government. Upon realizing Alex is his original attacker, his arc shifts from political opportunism to pure revenge, as he tortures Alex with Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, driving him to a suicide attempt. His character demonstrates how victimization can breed a desire for cruel vengeance.

Prison Chaplain

Godfrey Quigley

Motivation

His motivation is rooted in his religious and philosophical beliefs. He is driven by the conviction that moral choice is what defines humanity. He argues passionately that 'Goodness is something to be chosen. When a man cannot choose, he ceases to be a man.' His purpose is to question the ethics of the state's methods, regardless of the criminal's past actions.

Character Arc

The Prison Chaplain serves as the film's primary voice of moral and philosophical concern. He is initially one of the few characters who shows some genuine, albeit limited, concern for Alex. He is the first to object to the Ludovico Technique, not because he is fond of Alex, but on the theological grounds that it denies him free will. His arc is static; he remains consistent in his belief that true goodness cannot be coerced. He represents the film's central ethical dilemma.

P. R. Deltoid

Aubrey Morris

Motivation

His motivation appears to be maintaining the status quo and his own position. He wants Alex to stay out of trouble to avoid paperwork and complications. There is a lack of genuine care for Alex's well-being, replaced by a weary cynicism and a desire to enforce societal norms through intimidation and condescension.

Character Arc

Mr. Deltoid is Alex's post-corrective adviser, a government official tasked with keeping him out of trouble. He displays a cynical and somewhat lecherous attitude towards Alex, seemingly more concerned with appearances than with genuine rehabilitation. His arc is brief but telling: he goes from feigning concern to outright disgust and condemnation when Alex is finally arrested for murder, spitting in his face to signify that he has given up on him. He represents the failure and hypocrisy of the social support system.

Symbols & Motifs

Milk-Plus

The drug-laced milk that Alex and his droogs drink at the Korova Milk Bar symbolizes a perversion of innocence and the infantilization of youth in this society. Milk, typically a symbol of nourishment and childhood, is here corrupted and used as a prelude to violence. The whiteness of the milk also suggests a kind of sterile uniformity among the youth.

The film opens with a close-up of Alex drinking milk at the Korova Milk Bar. He explains that the milk is laced with drugs to 'sharpen you up and make you ready for a bit of the old ultra-violence.' The bar itself, with its female mannequins dispensing milk, further reinforces the themes of sexual objectification and corrupted innocence.

Beethoven's Ninth Symphony

Beethoven's music, particularly the Ninth Symphony, represents the pinnacle of human artistic achievement and, for Alex, a source of intense pleasure and emotional release. It symbolizes the complex duality of human nature, as it inspires both Alex's ecstatic fantasies and his violent rampages. After the Ludovico Technique, it becomes a symbol of his conditioning and loss of free will, as the state has co-opted this beautiful art and turned it into an instrument of torture for him.

Alex is frequently shown listening to Beethoven in his room, reaching a state of bliss. Later, during the Ludovico treatment, a film depicting Nazi atrocities is set to the Ninth Symphony. This association causes Alex immense suffering when he later hears the music, leading to his suicide attempt when Mr. Alexander uses it to torment him. His ability to once again enjoy the symphony at the film's end signifies the reversal of his conditioning.

Nadsat

The fictional slang spoken by Alex and his droogs, a mixture of Russian, English, and Cockney rhyming slang, symbolizes the distinct youth subculture and their alienation from mainstream society. It creates a linguistic barrier, immersing the audience in their world while also highlighting their otherness. The Russian influence in the language subtly hints at the film's themes of totalitarian control and societal decay.

Nadsat is used throughout Alex's narration and dialogue. Words like 'droog' (friend), 'moloko' (milk), and 'ultra-violence' are integral to the film's unique and unsettling atmosphere. The language is a key element that defines Alex's identity and his rebellious worldview.

The Clockwork Orange

The title itself is a central symbol. It represents the film's core theme: the mechanization of a living organism. An 'orange' is natural and organic, while 'clockwork' implies something mechanical and artificial. Thus, a 'clockwork orange' is a metaphor for Alex after the Ludovico Technique – a human being who has been stripped of his natural ability to make moral choices and is programmed to be good.

While the phrase is the title of a manuscript written by the character F. Alexander, its meaning permeates the entire film. The prison chaplain alludes to this concept when he argues that Alex, once 'cured', will no longer be a true human because he has lost the power of choice. Alex embodies the clockwork orange in the third act, appearing human but acting according to his mechanical conditioning.

Memorable Quotes

What's it going to be then, eh?

— Alex DeLarge

Context:

The line is first spoken by Alex in the Korova Milk Bar as he and his droogs contemplate their night of 'ultra-violence.' It serves as the opening line of the film's narration, immediately establishing the theme of choice.

Meaning:

This recurring question, which opens each of the story's three parts in the novel, frames the central theme of choice. It is a question about what action to take next, underscoring the importance of decision-making and free will. In each context, it carries a different weight: first as a prelude to violence, then as a question posed by the state about his fate, and finally, as a reflection on his regained ability to choose.

Goodness is something to be chosen. When a man cannot choose, he ceases to be a man.

— Prison Chaplain

Context:

The Prison Chaplain says this to Alex and later argues this point with the Minister of the Interior, protesting against the use of the Ludovico Technique. He is concerned that the treatment will destroy Alex's soul by removing his capacity for moral choice.

Meaning:

This quote is the most direct articulation of the film's central philosophical argument. It posits that morality is meaningless without free will. To be 'good' because one is forced to be is not true goodness; it is merely mechanical obedience. The chaplain argues that the ability to choose, even the choice to be evil, is essential to human identity.

It's funny how the colors of the real world only seem really real when you viddy them on the screen.

— Alex DeLarge

Context:

Alex narrates this thought while he is being subjected to the Ludovico Technique. He is strapped to a chair with his eyes clamped open, forced to watch violent films. The quote highlights the surreal and disorienting nature of his 'treatment'.

Meaning:

This line reflects on the nature of media and its power to mediate reality. It suggests a desensitization to real-life violence and a strange phenomenon where hyper-reality, as presented on a screen, can feel more potent than reality itself. This is particularly ironic given that he is being subjected to on-screen violence to cure him of his real-world violent tendencies.

I was cured, all right!

— Alex DeLarge

Context:

These are the last words Alex speaks in the film. He is in a hospital bed, surrounded by reporters and the Minister of the Interior, who has offered him a high-paying job. As photographers snap pictures, he fantasizes about violent, consensual sex, signifying his return to his former self.

Meaning:

This is the film's final, deeply ironic line. The 'cure' Alex refers to is not the Ludovico Technique's aversion to violence, but the reversal of that conditioning. He is 'cured' of his forced goodness and is free to be his violent self again. The line is triumphant and deeply cynical, suggesting that society has not reformed him but has simply returned him to his original state, now as a tool of the government, thus becoming complicit in his nature.

Philosophical Questions

Is it better to choose to be evil than to be forced to be good?

This is the central question of the film. 'A Clockwork Orange' explores this through the Ludovico Technique. Alex, a truly evil individual, is stripped of his ability to choose. The prison chaplain argues that this robs him of his humanity, as moral choice is the defining characteristic of mankind. The film forces the audience to confront the uncomfortable idea that the freedom to be evil is an essential component of free will. It suggests that a society that eliminates evil by eliminating choice is not a moral society, but a mechanistic one.

What is the true nature of humanity? Are we inherently good or evil?

The film presents a pessimistic view of human nature. Alex embodies the capacity for extreme cruelty, seemingly for its own sake. However, the 'good' characters are often just as monstrous. His former droogs become brutal police officers, and his victim, Mr. Alexander, becomes a cruel tormentor seeking revenge. The government is manipulative and self-serving. Kubrick seems to suggest that dark impulses are an integral part of humanity and that virtue is often just a mask for self-interest or a lack of opportunity for vice.

What are the ethical limits of crime and punishment?

The film serves as a powerful critique of state-sanctioned punishment that prioritizes social control over individual humanity. The Ludovico Technique is presented as a quick fix for crime, but it is a form of psychological torture that ultimately proves ineffective and reversible. It raises questions about whether the state has the right to fundamentally alter a person's personality, even a criminal's, in the name of public safety. The film argues that such methods are not only unethical but also dehumanizing, turning a man into a 'clockwork orange.'

Alternative Interpretations

The ending of 'A Clockwork Orange' is a primary subject of alternative interpretations. The final line, 'I was cured, all right,' can be read in several ways. The most common interpretation is deeply cynical: Alex has been 'cured' of his forced aversion to violence and is free to return to his old ways, with the added bonus of state approval. This suggests a cyclical nature of violence and the ultimate hypocrisy of the state, which is willing to embrace a monster to serve its political ends.

However, some viewers see a glimmer of change in Alex's final fantasy. Unlike his previous violent and non-consensual sexual acts, the fantasy at the end is of a playful, consensual encounter, applauded by figures of the establishment. This could be interpreted as a sign of maturation. Alex has not been 'cured' of his sexuality or aggression, but he has learned to channel it into a more socially acceptable, non-criminal form. He has made a deal with society, trading 'ultra-violence' for a more controlled, but still hedonistic, lifestyle. This reading suggests not a return to pure evil, but a pragmatic integration into a corrupt society.

Another layer of interpretation comes from the source material. The British edition of Anthony Burgess's novel included a final chapter, omitted from the American edition that Kubrick used, in which Alex naturally matures, grows bored of violence, and decides to settle down and start a family. Kubrick himself felt this ending was unconvincing and out of character. The debate continues as to whether Kubrick's ending is a more realistic conclusion to Alex's arc or a cynical departure from the author's ultimate message of hope and natural redemption.

Cultural Impact

When 'A Clockwork Orange' was released in 1971, it was met with a storm of controversy for its graphic depictions of violence and sexual assault, earning it an X rating in the US and leading to its eventual withdrawal by Kubrick himself in the UK amidst fears of copycat crimes. The film was created in a period of significant social upheaval and tapped into growing anxieties about juvenile delinquency, governmental overreach, and the effectiveness of psychological conditioning.

Its influence on cinema has been profound. The film's unique visual style, use of Nadsat slang, and unsettling blend of classical music with horrific violence have been referenced and parodied in countless films, television shows, and music videos. Directors have borrowed its themes of dystopian societies and its distinct cinematic techniques. The 'Kubrick Stare,' a shot where a character tilts their head down and stares intensely up at the camera, became an iconic visual shorthand for menacing insanity, and was famously used by Heath Ledger for his portrayal of the Joker in 'The Dark Knight.'

Philosophically, the film forced a mainstream conversation about free will, morality, and the ethics of crime and punishment that continues to be relevant. It became a cultural touchstone, with Alex and his droogs' distinctive bowler hats, white outfits, and codpieces becoming an iconic and enduring image in pop culture, frequently seen in fashion and as Halloween costumes. Despite the initial controversy, 'A Clockwork Orange' is now widely regarded as a cinematic masterpiece and a landmark of dystopian filmmaking, cementing its place as a powerful and provocative work of art.

Audience Reception

Audience reception for 'A Clockwork Orange' has always been polarized. Upon its release, many viewers were shocked and appalled by the graphic and stylized depictions of sexual violence, leading to accusations that the film glorified brutality and was morally irresponsible. This controversy was so intense in the UK that it led to the film's withdrawal from circulation. Critics were similarly divided, with some praising Kubrick's masterful direction, provocative ideas, and stunning visuals, while others condemned it as 'pointless' and 'bloodless,' warning that it could desensitize audiences to real violence.

Over the years, however, the film has achieved immense cult status and is now largely considered a cinematic masterpiece by many audiences and critics. Viewers praise Malcolm McDowell's iconic performance, the film's dark humor, its daring social commentary, and its thought-provoking exploration of free will. It is often cited for its incredible visual style and its lasting cultural impact. While the violent scenes remain difficult for many to watch, the film is widely recognized for its intellectual depth and artistic boldness, sparking debates that continue to this day.

Interesting Facts

- The unique 'Nadsat' slang used by the Droogs was created by author Anthony Burgess and is a mix of Russian, English, and Cockney rhyming slang.

- Malcolm McDowell, who played Alex, suffered a scratched cornea from the metal eye clamps used in the Ludovico Technique scenes and also cracked a rib during the stage demonstration scene.

- The iconic 'Singin' in the Rain' sequence was improvised by Malcolm McDowell during rehearsals. Director Stanley Kubrick loved it so much he immediately bought the rights to the song for $10,000.

- Due to a series of alleged copycat crimes and threats against his family, Stanley Kubrick withdrew the film from circulation in the United Kingdom in 1973. It was not officially available there again until after his death in 1999.

- The film was one of the first to use Dolby Noise Reduction for its sound mixing.

- The American version of the Anthony Burgess novel, which Kubrick based his screenplay on, omitted the final chapter where Alex grows up and renounces violence of his own accord. Kubrick was unaware of this final chapter when he made the film.

- The snake, Basil, that Alex keeps as a pet was not originally in the script. Kubrick added it after learning of McDowell's fear of reptiles.

- The film originally received an X rating in the United States. Kubrick later trimmed about 30 seconds of sexually explicit footage to secure an R rating.

Easter Eggs

In the record store scene, a soundtrack for Stanley Kubrick's previous film, '2001: A Space Odyssey' (1968), can be seen on display.

This is a self-referential nod from Kubrick to his own work, a common practice for many directors. It's a fun, hidden detail for fans of the director's filmography.

Also in the record store, the album 'Atom Heart Mother' by Pink Floyd is visible. Kubrick had approached the band to use their music, but they declined when he requested unlimited license to alter it.

This is a subtle acknowledgment of the music Kubrick had considered for the film. Despite the deal falling through, he included their album cover as a nod to the band.

When Alex is being processed into prison, his inmate number is not shown, but he is flanked by two guards wearing the numbers 665 and 667.

This is a subtle visual gag implying that Alex's prisoner number is 666, the 'Number of the Beast,' which is a symbolic reference to his evil nature.

In some of the newspaper clippings shown near the end of the film, Alex's surname is listed as 'Burgess.'

This is an homage to Anthony Burgess, the author of the novel upon which the film is based.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!