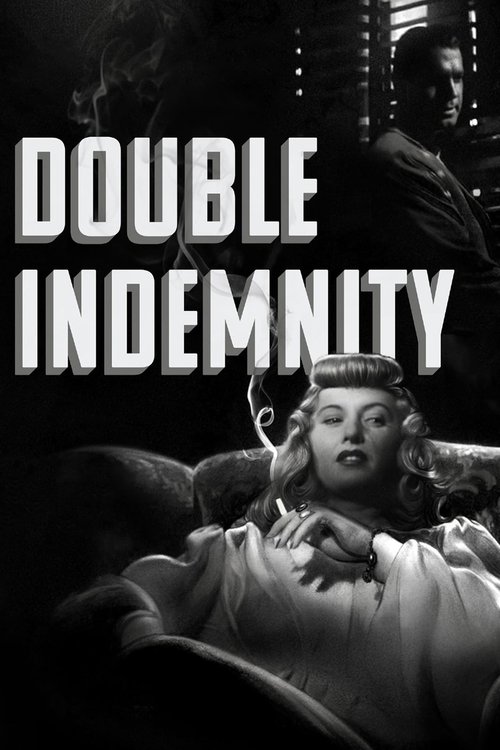

Double Indemnity

"It's love and murder at first sight!"

Overview

"Double Indemnity" begins at the end, with a bleeding Walter Neff, an insurance salesman, dictating a confession into his office Dictaphone. The film then flashes back to his fateful meeting with the alluring Phyllis Dietrichson. What starts as a routine house call about auto insurance quickly spirals into a web of lust and greed. Phyllis, trapped in a loveless marriage, seduces Neff into a scheme to murder her husband and cash in on a life insurance policy with a "double indemnity" clause, which pays out double for accidental deaths.

Neff, initially hesitant, is drawn in by Phyllis's charms and the challenge of committing the perfect crime against his own company. He meticulously plans every detail, from tricking Mr. Dietrichson into signing the policy to staging the murder to look like he fell from a moving train. However, Neff's brilliant plan begins to unravel under the scrutiny of his sharp-witted boss and friend, Barton Keyes, a claims investigator with an uncanny ability to sniff out fraudulent claims.

As Keyes inches closer to the truth, the once-passionate affair between Walter and Phyllis curdles into suspicion and paranoia. They become prisoners of their own crime, their trust eroding with each passing day. The film masterfully builds suspense as Neff realizes he was just a pawn in Phyllis's larger, more sinister game, leading to a deadly final confrontation.

Core Meaning

At its core, "Double Indemnity" is a cynical and cautionary tale about the corrupting influence of greed and lust. Director Billy Wilder paints a bleak picture of the American Dream, suggesting that beneath the veneer of suburban respectability lies a dark potential for moral decay. The film explores the idea that ordinary people, when faced with overwhelming temptation, are capable of extraordinary evil. It's a powerful critique of a society where money and desire can eclipse morality, leading individuals down a path of self-destruction from which there is no return. The narrative serves as a stark warning that the perfect crime is a fallacy, and that betrayal is the inevitable consequence of a partnership founded on deceit.

Thematic DNA

Greed and Moral Corruption

The pursuit of money is the central catalyst for the film's tragic events. Phyllis's desire for her husband's insurance money and Walter's ambition to outsmart the system he works for drive them to murder. Their actions illustrate how the allure of wealth can erode a person's moral compass, leading them to commit heinous acts. The film suggests that greed is an inherently corrupting force that, once it takes hold, leads to a downward spiral of deceit and violence.

The Femme Fatale and Seduction

Phyllis Dietrichson is the archetypal femme fatale, using her sexuality and manipulative charm as weapons to ensnare Walter Neff. She represents a dangerous and alluring temptation that preys on male desire and weakness. Her character challenges traditional gender roles of the era, portraying a woman who is not a passive victim but an active and ruthless agent of her own dark ambitions. The film explores how sexual obsession can blind a man to reason and lead to his ultimate downfall.

Deceit and Betrayal

The entire plot is built upon a foundation of lies. Walter and Phyllis deceive her husband, the insurance company, and ultimately, each other. Their partnership, born of a criminal conspiracy, is inherently unstable. As the investigation tightens, their initial trust disintegrates into mutual suspicion and paranoia. The film powerfully illustrates that a relationship built on deceit is doomed to end in betrayal, as the partners in crime inevitably turn on one another to save themselves.

Fate and Fatalism

From the opening scene of Walter's confession, the film establishes a sense of inescapable doom. His narration frames the story as a foregone conclusion, suggesting that once he made the initial choice to get involved with Phyllis, his fate was sealed. This fatalistic tone is a hallmark of film noir, portraying characters who are trapped by their own choices and hurtling towards a tragic end they cannot avoid. As Walter says, they're on a trolley car that goes "straight to the end of the line."

Character Analysis

Walter Neff

Fred MacMurray

Motivation

Neff is motivated by a combination of lust for Phyllis, greed for the insurance money, and, most importantly, hubris. He believes he is smart enough to commit the perfect crime and outwit the very company he works for, a challenge that appeals to his ego. As he confesses, the idea of cheating the system had been a long-held fantasy.

Character Arc

Walter Neff begins as a smooth-talking, successful insurance salesman who thinks he knows all the angles. His cockiness and latent desire to beat the system make him susceptible to Phyllis's manipulation. He transforms from a morally ambiguous but law-abiding citizen into a cold-blooded murderer and accomplice. His arc is a steady descent into a personal hell of his own making, trading his integrity for a fantasy of money and a woman he never truly possesses. By the end, stripped of his bravado, he is a broken, dying man seeking a final moment of connection with his friend, Keyes.

Phyllis Dietrichson

Barbara Stanwyck

Motivation

Phyllis is driven by pure greed and a lust for power and independence. She sees men as tools to be used and disposed of to achieve her financial goals. She has no genuine affection for anyone, including Walter, and is solely focused on acquiring her husband's insurance payout.

Character Arc

Phyllis Dietrichson shows little to no character arc; she is a master manipulator from the very beginning. She presents herself as a victim trapped in an unhappy marriage, but this is merely a facade to hide her cold, calculating, and sociopathic nature. As the film progresses, the true extent of her ruthlessness is revealed. She is not just a woman who wants to be free of her husband, but a serial manipulator who uses and discards people for her own gain. Her final, fleeting moment of hesitation before shooting Walter a second time is the only hint of a deeper emotion, but it comes too late.

Barton Keyes

Edward G. Robinson

Motivation

Keyes is motivated by an uncompromising sense of justice and a deep-seated pride in his work. He is obsessed with uncovering insurance fraud and ensuring that no one cheats the system. His motivation is not financial but ethical; he believes in order and accountability. His friendship with Walter adds a personal stake to his investigation.

Character Arc

Barton Keyes is the unwavering moral center of the film. He is a brilliant and dogged claims investigator who trusts his "little man"—his intuition—above all else. He remains consistent in his dedication to his job and his pursuit of the truth. His arc is one of disillusionment. He begins with a deep, almost paternal, affection for Walter. His discovery of Walter's betrayal is a profound personal blow, transforming his professional investigation into a tragic confrontation with the corruption of his closest friend.

Symbols & Motifs

Venetian Blinds

The iconic use of shadows cast by Venetian blinds symbolizes the moral ambiguity and entrapment of the characters. The striped shadows create a visual metaphor for prison bars, suggesting that Walter and Phyllis are prisoners of their own scheme long before they are caught. The interplay of light and shadow reflects their divided natures and the dark, hidden aspects of their personalities.

This visual motif is used repeatedly in key scenes, particularly in Walter's apartment and the Dietrichson home. The shadows fall across the characters' faces and bodies, visually segmenting them and highlighting the fractured, duplicitous nature of their lives.

Phyllis's Anklet

The cheap, gold anklet Phyllis wears is a symbol of her seductive power and her underlying phoniness. It's the first thing that catches Walter's eye, representing the bait in her trap. It signifies a certain kind of dangerous, alluring femininity that is both enticing and a warning of the moral corruption that lies beneath her polished exterior.

The camera focuses on the anklet when Walter first meets Phyllis as she stands at the top of the stairs, clad only in a towel. This moment establishes her as the temptress and marks the beginning of Walter's infatuation and subsequent downfall.

The Dictaphone

Walter's confession into the Dictaphone symbolizes a desperate need for absolution and a final, futile attempt to control the narrative of his downfall. It frames the entire story as a memory, emphasizing the fatalism of the plot. By recording his story, he is both documenting his crime and acknowledging his inevitable end, turning his personal tragedy into a formal record.

The film opens and closes with Walter in his office, speaking into the Dictaphone. This framing device establishes the flashback structure and immediately informs the audience that the plan has failed, creating a sense of impending doom that hangs over the entire film.

The Supermarket

The clandestine meetings between Walter and Phyllis in a busy supermarket symbolize the transactional and mundane nature of their murderous plot. By discussing their dark plans amidst the bright, ordinary setting of a grocery store, the film juxtaposes the horrific nature of their crime with the banality of everyday life, suggesting that evil can lurk beneath the most commonplace surfaces.

Walter and Phyllis meet secretly in the aisles of a local supermarket to exchange information and plan their next moves. The stark lighting and public setting of these meetings create a tense and unsettling atmosphere, highlighting the risk and paranoia inherent in their conspiracy.

Memorable Quotes

I killed him for money and for a woman, and I didn't get the money and I didn't get the woman.

— Walter Neff

Context:

This is one of the first lines Walter speaks into the Dictaphone at the beginning of the film, immediately after stating his name and occupation. He is bleeding from a gunshot wound and knows he is dying, framing the entire story as a confession of a doomed man.

Meaning:

This line, spoken in Walter's opening confession, encapsulates the utter failure and futility of his criminal endeavor. It's a stark, cynical summary of the entire plot, highlighting the tragic irony that he sacrificed his life and soul for rewards he would never obtain. It perfectly sets the film's bleak, fatalistic tone.

Yes, I killed him. I killed him for money - and a woman - and I didn't get the money and I didn't get the woman. Pretty, isn't it?

— Walter Neff

Context:

Walter says this to Barton Keyes in the final scene, after Keyes has found him dying in the office. It is his final, verbal confession to his friend, summarizing the pathetic outcome of his life's greatest mistake.

Meaning:

A slight variation of the opening line, this quote is delivered with a heavy dose of sarcasm and self-loathing at the film's climax. The addition of "Pretty, isn't it?" underscores his complete disillusionment and the grotesque absurdity of his situation. It's a bitter acknowledgment of how his 'perfect' plan has collapsed into a meaningless tragedy.

How could I have known that murder can sometimes smell like honeysuckle?

— Walter Neff

Context:

Walter reflects on his first visit to the Dietrichson house. The memory of the honeysuckle smell is tied directly to his first encounter with Phyllis, the moment his descent began.

Meaning:

This poetic line from Walter's narration juxtaposes the sweet, ordinary scent of honeysuckle with the horrific act of murder. It symbolizes his initial naivete and how beauty and innocence can mask deadly intentions. It captures the moment he was drawn into a dark world that was deceptively alluring on the surface.

We're both rotten.

— Walter Neff

Context:

During a tense meeting, Walter confronts Phyllis with the knowledge that she has been seeing another man, Nino Zachetti. He realizes the full extent of her deception and their shared moral bankruptcy.

Meaning:

This is a moment of stark realization for Walter. After Phyllis admits she was using him, he equates them both, acknowledging his own corruption. However, Phyllis's chilling reply, "Only you're a little more rotten," reveals her complete lack of a moral compass, as she coolly assesses their degrees of depravity.

I love you, too.

— Walter Neff

Context:

After a tense conversation in Walter's office, Keyes berates him before storming out. Walter's quiet reply is delivered after Keyes has left, revealing his true feelings for the man he is actively deceiving. He repeats the sentiment in the film's final moments.

Meaning:

This is Walter's poignant, ironic reply to Keyes's typically gruff dismissal. Beneath the surface, it reveals the genuine, albeit complicated, affection Walter feels for his friend and mentor. The line becomes tragic in the final scene when Keyes's actions prove his own deep-seated loyalty and friendship, a loyalty Walter betrayed.

Philosophical Questions

Are ordinary people inherently capable of great evil?

The film explores this question through its protagonist, Walter Neff. He is not a hardened criminal but an ordinary, successful salesman. His descent into murder is portrayed as a gradual slide, initiated by temptation and fueled by his own ego. The film suggests that the capacity for evil is not limited to societal outliers but may lie dormant in anyone, waiting for the right combination of circumstances—lust, greed, and opportunity—to be unleashed. It challenges the audience to consider the fragility of their own moral foundations.

Can a relationship built on deceit ever result in genuine connection?

"Double Indemnity" answers this with a resounding no. The partnership between Walter and Phyllis is transactional from the start, based on mutual exploitation. While they share a powerful physical attraction, their bond is ultimately hollow. As soon as pressure is applied, it shatters into paranoia and betrayal. The film argues that without trust and honesty, any form of relationship, whether romantic or criminal, is doomed to self-destruct.

Is there such a thing as a 'perfect crime'?

Walter Neff is obsessed with this idea, believing his insider knowledge gives him the ability to pull it off. The film systematically deconstructs this fantasy. It shows how unforeseen variables, human error, and uncontrollable emotions inevitably lead to mistakes. More profoundly, it suggests that even if the crime isn't discovered by the authorities, the psychological toll—the guilt, suspicion, and paranoia—creates a prison from which the criminals cannot escape, making the notion of a 'perfect' outcome an illusion.

Alternative Interpretations

While the most common interpretation sees Walter Neff as a victim ensnared by the manipulative Phyllis, an alternative reading suggests Neff is a more active participant in his own downfall, perhaps even the primary architect. This perspective argues that Phyllis merely provides the opportunity for a crime Neff has subconsciously desired to commit for years. His confession reveals a long-standing fascination with beating the insurance system from the inside. In this light, Phyllis is less of a puppeteer and more of a catalyst, unleashing a darkness that was already latent within Walter.

Another interpretation focuses on the homoerotic subtext in the relationship between Walter and Barton Keyes. Their deep bond, mutual respect, and emotional intimacy—culminating in Walter's dying declaration, "I love you, too"—can be seen as the film's central relationship. From this perspective, Phyllis acts as the disruptive force, a destructive female presence that comes between the two men. Walter's crime is not just a betrayal of the company, but a profound personal betrayal of Keyes, and his death in Keyes's presence is a tragic, intimate reconciliation.

Cultural Impact

"Double Indemnity" is widely regarded as a masterpiece and a cornerstone of the film noir genre, setting the template for countless films that followed. Released in 1944, during a time of social unease and shifting morals in post-Depression, wartime America, the film's dark, cynical tone resonated with audiences and critics. It pushed the boundaries of the restrictive Hays Code, dealing with taboo subjects like adultery and cold-blooded murder in a way that was shocking for its time.

Its visual style, particularly John F. Seitz's masterful use of chiaroscuro (low-key lighting with stark contrasts), defined the look of film noir. The use of Venetian blind shadows became an iconic visual shorthand for entrapment and moral ambiguity. The film solidified the archetype of the femme fatale in popular culture, with Barbara Stanwyck's portrayal of Phyllis Dietrichson becoming the standard against which all subsequent cinematic seductresses are measured.

"Double Indemnity" was a critical and commercial success, demonstrating that crime stories could be elevated to high art. Its influence can be seen in numerous later films, from neo-noirs like "Body Heat" (1981) to thrillers that explore similar themes of greed and betrayal. The film's sophisticated, witty, and hard-boiled dialogue, crafted by Wilder and Chandler, also set a new standard for screenwriting. It remains a powerful and enduring classic, studied by film students and revered by cinephiles for its near-perfect construction and timeless exploration of human weakness.

Audience Reception

Upon its release, "Double Indemnity" was largely praised by critics for its taut storytelling, sharp dialogue, and daring subject matter. Reviewers noted its grim realism and suspense, with some comparing it to French cinema for its gritty tone. Audiences were captivated by the thrilling plot and the strong performances, particularly Barbara Stanwyck's chilling portrayal of the femme fatale. Fred MacMurray's against-type performance as a weak-willed heel was also a point of surprise and acclaim.

However, the film's cynical and dark themes were controversial for the time. Its depiction of cold-blooded murder and adultery, presented without clear heroes, was shocking to some. Despite this, the film was a box office success. Over the decades, its reputation has only grown, and it is now almost universally regarded by audiences and critics as a cinematic masterpiece and the quintessential film noir. Viewers consistently praise its intricate plot, atmospheric cinematography, and the crackling chemistry between the leads.

Interesting Facts

- The film was based on James M. Cain's 1936 novella, which itself was inspired by the real-life 1927 murder of Albert Snyder, committed by his wife Ruth Snyder and her lover, Judd Gray, for insurance money.

- Barbara Stanwyck was initially hesitant to take the role of a cold-blooded killer, fearing it would harm her career. Director Billy Wilder famously convinced her by asking, "Well, are you a mouse or an actress?"

- Finding a male lead was difficult, as many established actors, including Alan Ladd and George Raft, turned down the role of the morally weak Walter Neff. Fred MacMurray, known for light comedies, took the role, which dramatically changed his career trajectory.

- The screenplay was co-written by Billy Wilder and famed detective novelist Raymond Chandler. The two reportedly despised working with each other, frequently arguing over the script.

- The distinctive blonde wig worn by Barbara Stanwyck was intentionally chosen by Wilder to make the character look cheap and phony, reflecting her duplicitous nature.

- An original ending was filmed that depicted Walter Neff's execution in the gas chamber, with Keyes watching. Wilder ultimately decided to cut the scene, feeling the film was stronger ending with the final confrontation between the two friends in the office.

- The Hays Code, Hollywood's censorship board, presented a major challenge. The story of adultery and murder was considered highly objectionable, and Wilder and Chandler had to carefully navigate the code's restrictions.

- The film was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actress, but famously won none, losing many to the much lighter film "Going My Way."

Easter Eggs

Cameo by screenwriter Raymond Chandler

About 16 minutes into the film, as Walter Neff walks past Barton Keyes's office, a man sitting on a bench outside looks up from the book he is reading. This man is Raymond Chandler, the celebrated crime novelist who co-wrote the screenplay.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!