Full Metal Jacket

"In Vietnam, the wind doesn't blow. It sucks."

Overview

Stanley Kubrick's "Full Metal Jacket" is a stark, two-part examination of the Vietnam War's dehumanizing effect on soldiers. The first half of the film is set at the Parris Island Marine Corps recruit depot in South Carolina. Here, a group of new recruits, including the wisecracking Private "Joker" (Matthew Modine) and the overweight, struggling Leonard Lawrence, nicknamed "Gomer Pyle" (Vincent D'Onofrio), are subjected to the brutal and relentless training of Gunnery Sergeant Hartman (R. Lee Ermey). Hartman's method is to break the men down, strip them of their individuality, and rebuild them as unthinking killers.

The second half of the film shifts to Vietnam during the Tet Offensive. Joker, now a combat correspondent for the military newspaper Stars and Stripes, is sent to the front lines. He reunites with his boot camp peer, Cowboy, and joins the Lusthog Squad, experiencing the chaotic and brutal reality of urban warfare in the city of Huế. This segment contrasts the sterile, controlled environment of boot camp with the unpredictable and morally ambiguous nature of actual combat, pushing Joker's cynical detachment to its absolute limit.

Core Meaning

"Full Metal Jacket" is a profound critique of the military's process of dehumanization and the psychological devastation of war. Director Stanley Kubrick explores the idea that to create a soldier capable of killing, one must first destroy the individual. The film's bifurcated structure starkly contrasts the systematic stripping away of humanity in training with the chaotic and absurd reality of war itself. The core message revolves around the "duality of man," a concept explicitly mentioned by Private Joker. It suggests that within every person, there's a capacity for both good and evil, peace and violence, and that the crucible of war forces these contradictory elements into a volatile and often tragic confrontation.

The film argues that the 'masculinity' forged in boot camp is a brittle, performative construct that shatters when faced with the genuine horrors of combat. Ultimately, the movie posits that war is a fundamentally insane endeavor that corrupts innocence, obliterates individuality, and leaves survivors in a psychological "world of shit," forever changed and disconnected from the world they once knew.

Thematic DNA

Dehumanization and the Loss of Individuality

The film's first act is a masterclass in depicting systematic dehumanization. Gunnery Sergeant Hartman's entire purpose is to strip the recruits of their identities, replacing their names with derogatory nicknames and their individuality with collective obedience. The process begins with the shaving of their heads, creating a visual uniformity. They are taught to refer to their rifle as their best friend, a tool that will replace human connection. Private Pyle's tragic arc is the ultimate example of this theme; the process doesn't make him a killer in the way Hartman intends but instead breaks his mind, leading to a violent psychotic break. In Vietnam, this dehumanization manifests as a callous disregard for life, seen in the helicopter gunner who shoots civilians and the soldiers' dark, cynical humor.

The Duality of Man

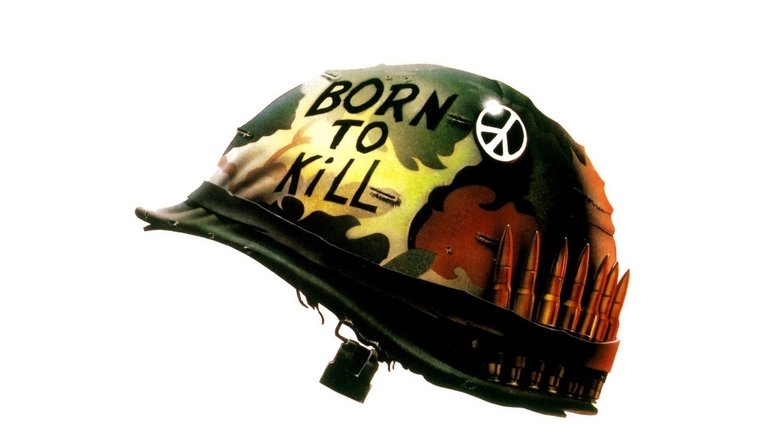

This theme is most famously encapsulated by Private Joker's helmet, which bears the inscription "Born to Kill," alongside a peace symbol button on his jacket. When confronted by a colonel, Joker explains it's a statement on "the duality of man. The Jungian thing." The film constantly explores this contradiction: the capacity for violence and compassion existing within a single person. Joker is a cynical wisecracker who wants to get a "confirmed kill," yet he is also the most compassionate character, attempting to help Pyle and ultimately mercy-killing the female sniper. This theme suggests that the soldiers are caught between their ingrained humanity and the killer instinct the military has forged in them.

The Absurdity and Insanity of War

Kubrick portrays war not as a glorious or heroic endeavor, but as a chaotic, senseless, and deeply ironic spectacle. The dialogue is filled with black humor, and situations often defy logic. For example, a general orders Joker to change his peace button, concerned more with appearances than the surrounding death and destruction. The soldiers are interviewed by a film crew, striking poses and delivering soundbites that clash with the grim reality. The film's climax, where the soldiers march through the burning ruins of Huế singing the "Mickey Mouse March," is the ultimate expression of this absurdity—a childish tune juxtaposed with the horrors of war, signifying their lost innocence and regression into a new, terrifying form of childhood.

Performative Masculinity

The film scrutinizes the nature of masculinity, particularly the hyper-masculine ideal promoted by the military. Hartman constantly attacks the recruits' manhood, calling them "ladies" and using homophobic slurs to motivate them. Manhood is presented as an aggressive, emotionless state that the recruits must aspire to, often by mimicking the tough-guy persona of actors like John Wayne. Characters like Animal Mother embody this ideal, being pure, unthinking aggression. However, the film suggests this is a brittle performance. Cowboy, when thrust into a leadership role, is indecisive and unable to live up to the ideal, leading to his death. The constant entanglement of sexuality with violence, like the famous "This is my rifle, this is my gun" chant, further critiques this toxic form of masculinity.

Character Analysis

Private J.T. 'Joker' Davis

Matthew Modine

Motivation

Initially motivated by a desire to survive boot camp with his wit intact, his motivation in Vietnam is to observe and report on the war, to "see exotic Vietnam... and kill them." Ultimately, his core motivation is to navigate the moral chaos of war while retaining some piece of his individual self, a struggle encapsulated by his helmet and peace button.

Character Arc

Joker begins as a cynical, intelligent recruit who uses humor as a defense mechanism against the brutality of boot camp. He displays compassion by trying to help Private Pyle. In Vietnam, he works as a journalist, maintaining a detached, observational role. However, the Tet Offensive forces him into combat, where his ironic detachment is eroded by the visceral reality of war. His arc culminates in the mercy-killing of the female sniper, an act that resolves his internal conflict between his humanity and his training. He ends the film a hardened survivor, admitting he's "in a world of shit... but I am alive. And I am not afraid," signifying his full, tragic transformation into a soldier.

Gunnery Sergeant Hartman

R. Lee Ermey

Motivation

His sole motivation is to transform his "maggots" into hardened Marines capable of killing and surviving in combat. He believes wholeheartedly in the dehumanizing process, seeing it as a necessary means to a vital end.

Character Arc

Hartman is a static character who serves as the embodiment of the Marine Corps' brutal training philosophy. His purpose is to break down recruits and remold them into killers. He is relentlessly abusive, profane, and cruel, yet he shows a perverse form of pride when a recruit meets his standards. His arc is short and violent; he succeeds in turning Pyle into a proficient marksman but fails to see that he has also driven him completely insane. His belief in his own system's infallibility leads directly to his shocking death at Pyle's hands, a testament to the destructive potential of his methods.

Private Leonard 'Gomer Pyle' Lawrence

Vincent D'Onofrio

Motivation

Pyle's initial motivation is simply to survive the torment of boot camp and meet Hartman's impossible standards. After being broken, his motivation becomes a terrifying fusion of the Rifleman's Creed and a desire for revenge against his tormentor.

Character Arc

Pyle enters boot camp as an overweight, clumsy, and simple-minded recruit, making him the primary target of Hartman's abuse. Initially, he is inept, but after a brutal hazing incident (the 'blanket party'), he begins to improve as a soldier, showing exceptional skill in marksmanship. However, this external improvement masks a complete internal collapse. He descends into madness, talking to his rifle as if it's his only friend. His arc concludes in the film's most horrifying sequence: he murders Hartman, the source of his torment, before killing himself, his transformation from bumbling innocent to psychotic killer complete.

Private 'Animal Mother'

Adam Baldwin

Motivation

His motivation is simple and direct: to kill the enemy. He is driven by bloodlust and a primal instinct for combat.

Character Arc

Animal Mother is introduced in the second half of the film and represents the perfect product of the military machine that Hartman tried to create. He is a hulking, aggressive M60 gunner who lives for combat and has no moral ambiguity about killing. His helmet reads "I Am Become Death." He has little to no character arc; he is pure, primal violence from beginning to end. He clashes with Joker's intellectualism but ultimately takes charge after Cowboy is killed, driven by a simple desire for revenge. He represents what Pyle might have become if his mind hadn't snapped, a human being successfully turned into a weapon.

Symbols & Motifs

Joker's Helmet and Peace Button

This combination is the film's central symbol, representing the "duality of man." The "Born to Kill" inscription signifies the killer identity the Marine Corps has imposed on him, while the peace symbol represents his lingering humanity, individuality, and perhaps a repressed pacifist nature. It's a visual manifestation of the internal conflict that defines his character and the film's core theme.

Joker wears this combination throughout his time in Vietnam. It becomes a point of contention when a colonel questions him about it, leading to Joker's famous line about Jungian duality. Symbolically, as Joker prepares to execute the wounded sniper at the end of the film, his peace button is hidden from view, suggesting that the "killer" side has finally won out in that moment.

The Rifle

The rifle is depicted as an extension of the Marine's identity and a phallic symbol of power and masculinity. The recruits are forced to name their rifles and sleep with them, treating them as their only companions. The infamous chant, "This is my rifle, this is my gun. This is for fighting, this is for fun," explicitly links the weapon to male genitalia and the acts of killing and sex.

This symbolism is established in boot camp, most notably through the Rifleman's Creed, which Private Pyle recites manically before his murder-suicide. For Pyle, the rifle becomes a source of empowerment and, ultimately, the instrument of his complete mental breakdown. In the final confrontation, Joker's rifle jams, symbolizing his impotence and hesitation at the moment of truth.

The Mickey Mouse March

The song symbolizes the soldiers' loss of innocence and their psychological regression. By singing a children's song while marching through a hellish landscape, they reveal how the dehumanizing process of war has infantilized them, turning them into obedient children following orders in a macabre parody of their former selves. It's a deeply ironic and unsettling conclusion, suggesting they have found a twisted form of camaraderie and acceptance in their shared trauma.

The film ends with the surviving members of the Lusthog Squad marching through the fiery ruins of Huế at dusk, singing the theme song from "The Mickey Mouse Club." This happens immediately after Joker has killed the young female sniper, completing his transformation into a killer.

The Latrine (The Head)

The latrine, or "head," in military parlance, serves as a stage for critical turning points and confessions. In the sterile, ordered world of the barracks, it is a place of relative privacy where the psychological pressure of boot camp boils over. It symbolizes a space of both ritual cleansing and profane violence, where the film's illusions of order and control are shattered.

Private Joker is ordered to clean the head with Cowboy, where Hartman demands it be so clean "the Virgin Mary herself would be proud to go in and take a dump." The first act culminates in the latrine, a pristine, white-tiled space that becomes the setting for Private Pyle's mental breakdown, his murder of Sergeant Hartman, and his own suicide. The stark white is violated by the bright red of blood, marking the violent end of their training and innocence.

Memorable Quotes

I am Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, your senior drill instructor. From now on you will speak only when spoken to, and the first and last words out of your filthy sewers will be 'Sir.' Do you maggots understand that?

— Gunnery Sergeant Hartman

Context:

Spoken in the first scene in the barracks, as Hartman addresses the new recruits for the first time after they've had their heads shaved.

Meaning:

This is Hartman's opening salvo, establishing his absolute authority and the complete stripping of the recruits' identities. It sets the tone for the entire boot camp sequence, defining the brutal power dynamic that will shape the new Marines.

This is my rifle. There are many like it, but this one is mine. My rifle is my best friend. It is my life.

— The Recruits (reciting the Rifleman's Creed)

Context:

The recruits recite this creed during their training. It is later repeated chillingly by a deranged Private Pyle in the latrine just before he murders Sergeant Hartman and commits suicide.

Meaning:

This quote, part of the Rifleman's Creed, symbolizes the process of dehumanization and the replacement of human connection with a devotion to a weapon. It highlights the psychological conditioning used to turn men into killers, making the rifle an extension of their own being.

I think I was trying to suggest something about the duality of man, sir. The Jungian thing.

— Private Joker

Context:

Joker says this to a hard-nosed colonel in the field who questions the contradiction of him wearing a peace symbol on his body armor while having "Born to Kill" written on his helmet.

Meaning:

This is the film's thesis statement, delivered with Joker's characteristic wit. It explicitly names the central theme of the film: the inherent contradiction within humanity, the capacity for both peace and violence, which is brought to the forefront by the pressures of war.

Seven-six-two millimeter. Full metal jacket.

— Private Pyle

Context:

Spoken in the latrine during the film's first-act climax. Joker, on fire watch, discovers Pyle loading his rifle and asks him if the rounds are live. This is Pyle's deadpan response.

Meaning:

These chillingly calm words mark the completion of Pyle's transformation and the point of no return. He identifies the bullets—the film's namesake—not as ammunition, but as an integral part of his new, deadly identity. It's a moment of terrifying clarity in his madness.

I'm in a world of shit, yes. But I am alive. And I am not afraid.

— Private Joker

Context:

The final lines of the film, delivered in a voiceover as the squad marches through the burning ruins of Huế, singing the "Mickey Mouse March" after Joker has killed the sniper.

Meaning:

Joker's final voiceover narration summarizes his transformation. He acknowledges the hellish reality of his situation but also declares his survival and the shedding of his fear. It's an ambiguous ending: is this a victory, or has he simply become numb and fully assimilated into the machinery of war, having lost the part of him that was afraid?

Philosophical Questions

What is the true nature of humanity: are we inherently violent or peaceful?

The film delves into this question through the "duality of man" theme. The boot camp sequence suggests that extreme violence is not natural but must be brutally conditioned into men. Sergeant Hartman's job is to suppress compassion and elevate a latent killer instinct. Joker's internal struggle, symbolized by his helmet and peace button, embodies this philosophical conflict. The film doesn't provide a definitive answer but suggests that civilization is a thin veneer over a primal capacity for violence, a capacity the military exists to exploit and weaponize.

Can individuality survive within a system designed to eradicate it?

"Full Metal Jacket" presents a grim outlook on this question. The entire first half is dedicated to showing the systematic destruction of individuality. Joker, the most individualistic character, struggles to maintain his identity through wit and irony. However, by the end, his act of killing the sniper suggests his individuality has been subsumed by his training. The final scene, with the soldiers marching in unison singing a childish song, implies that the collective has triumphed over the individual. Pyle's story offers an even darker answer: his attempt to conform while retaining a piece of himself results not in survival, but in a complete psychotic break.

Where is the line between sanity and insanity in the context of war?

The film continually blurs this line. Hartman's methods are sociopathic, yet they are the sanctioned procedure for creating a soldier. Private Pyle is driven insane by this process, but his resulting marksmanship skills are praised. In Vietnam, the soldiers engage in gallows humor and collect souvenirs from corpses (like Crazy Earl), behaviors that would be considered insane in civilian life but are coping mechanisms in war. The film suggests that war itself is an insane environment and that to survive it, one must adopt a form of madness. The ultimate question is whether characters like Animal Mother are sane for adapting perfectly to an insane world, or if Joker is the sane one for struggling against it.

Alternative Interpretations

While the film is widely seen as a critique of war and dehumanization, several alternative or deeper interpretations exist, particularly regarding its structure and ending.

A Three-Act Structure: Some analysts argue the film isn't two parts but three distinct acts: the dehumanization of boot camp, the surreal detachment of Joker's time in Da Nang as a journalist, and the final descent into the hell of the Battle of Huế. In this view, the middle act serves as a fragile limbo between the structured violence of training and the chaotic violence of combat.

Pyle and Animal Mother as Doppelgängers: One popular interpretation posits that Animal Mother is the soldier Private Pyle was meant to become—the perfect killing machine. Pyle's humanity and instability prevented him from completing this transformation, leading to his self-destruction. Animal Mother, who lacks Pyle's vulnerability, is the grimly successful product of the same system that destroyed Pyle.

Joker's Final Narration: The meaning of Joker's final line, "I am alive, and I am not afraid," is heavily debated. A straightforward reading suggests he has survived and come to terms with the horror. A more cynical interpretation is that he is not afraid because he has finally been fully dehumanized. He has lost the fear and compassion that made him human, completing the transformation Hartman began. His statement of being "happy" is the ultimate irony, as he has become another hollowed-out cog in the war machine.

Cultural Impact

"Full Metal Jacket" was released in 1987, entering a cinematic landscape already populated by significant Vietnam War films like "Platoon" and "Apocalypse Now." However, it distinguished itself with its unique two-part structure and Kubrick's cold, detached directorial style. The first half of the film, focusing on the brutalizing process of boot camp, has had a particularly profound cultural impact. R. Lee Ermey's performance as Gunnery Sergeant Hartman became instantly iconic, and his profanity-laced, endlessly quotable tirades have been parodied and referenced throughout pop culture, from other films and TV shows to video games like World of Warcraft and Fallout 3.

Critically, the film was praised for its technical brilliance, dark humor, and the intensity of its first act, though some critics found the second half more disjointed and conventional. Nevertheless, it earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay. The film's exploration of themes like dehumanization, the duality of man, and the psychological toll of war has solidified its place as a staple in discussions about war cinema. Phrases like "the duality of man" and images like Joker's helmet have become cultural shorthand for the internal conflicts faced by soldiers. Over time, its reputation has grown, and it is now widely regarded as one of the most powerful and unflinching anti-war films ever made.

Audience Reception

Audience reception for "Full Metal Jacket" has been strong and enduring, though it was initially met with some division. Many viewers praise the film's first half as one of the most intense and powerful sequences in cinema history, with R. Lee Ermey's performance as Gunnery Sergeant Hartman being universally lauded. The dark humor, sharp dialogue, and unflinching depiction of military training are frequently cited as high points. However, a common point of criticism, particularly upon its initial release, was that the second half of the film in Vietnam felt less focused and powerful than the Parris Island segment. Some viewers found the episodic nature of the war scenes to be disjointed compared to the tightly constructed narrative of the first act. Despite this, the film's reputation has only grown over time, and it is now widely considered a masterpiece of the war genre. Audiences appreciate its cynical tone, psychological depth, and refusal to offer easy answers or patriotic sentiment. The ending, with the soldiers singing the "Mickey Mouse March," is often cited as a haunting and brilliant conclusion.

Interesting Facts

- The film was shot almost entirely in England. The Parris Island boot camp was recreated at Bassingbourn Barracks in Cambridgeshire, while the ruined city of Huế was a derelict gasworks in Beckton, East London.

- R. Lee Ermey, who played Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, was originally hired only as a technical advisor. A real-life former Marine drill instructor, Ermey filmed an audition tape of himself yelling insults and so impressed Stanley Kubrick that he was given the role.

- Ermey improvised a significant portion of his dialogue. Kubrick allowed this to make the performance more authentic, having Ermey write around 150 pages of insults.

- Vincent D'Onofrio gained 70 pounds for the role of Private Pyle, breaking the then-record for weight gained by an actor for a film role, previously held by Robert De Niro for "Raging Bull".

- The score for the film was composed by Stanley Kubrick's daughter, Vivian Kubrick, under the pseudonym "Abigail Mead".

- Private Joker's real name, J.T. Davis, is a reference to Specialist James T. Davis, one of the first American service members killed in Vietnam in 1961.

- To maintain authenticity during the boot camp scenes, the actors playing recruits had their heads shaved once a week.

- A scene was filmed but cut in which Marines play soccer with a severed human head. Kubrick reportedly found it too grotesque.

- The entire production was so long that in the time it took to film, actor Matthew Modine got married, his wife became pregnant, and their child was born and celebrated a first birthday.

- Bruce Willis was offered a role but had to decline due to his commitment to the TV series "Moonlighting."

Easter Eggs

During the death scene of the character Cowboy, a building in the background bears a striking resemblance to the alien monolith from Stanley Kubrick's earlier film, "2001: A Space Odyssey."

This is a subtle visual nod from Kubrick to his own work. While its meaning is open to interpretation, it could suggest a moment of transformation or a confrontation with an unknowable, imposing force, much like the monolith in 2001. In the context of Cowboy's death, it adds a layer of surreal, cosmic significance to the chaos of war.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!