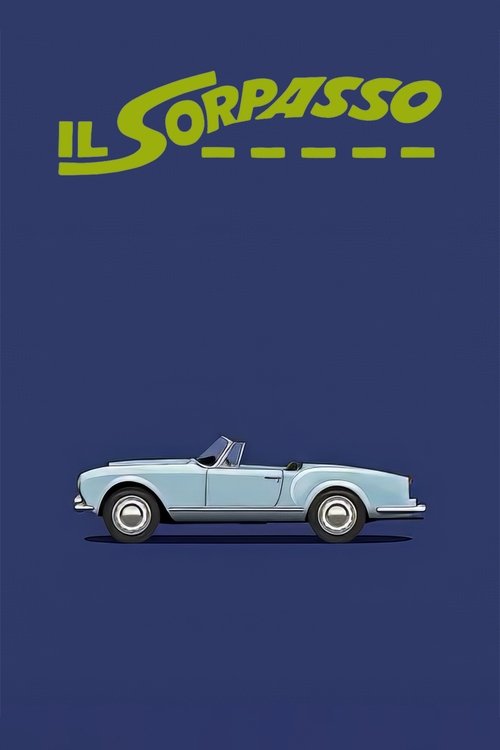

Il Sorpasso

Il sorpasso

Overview

Set during the Ferragosto holiday, Il Sorpasso begins in a nearly deserted Rome. Bruno Cortona (Vittorio Gassman), a boisterous, impulsive 36-year-old, coaxes Roberto Mariani (Jean-Louis Trintignant), a shy and serious law student, away from his books for what is supposed to be a short drink. This brief outing unexpectedly transforms into a two-day road trip along the Via Aurelia toward Tuscany in Bruno's convertible Lancia Aurelia B24.

As they travel, the stark differences between the two men become apparent. Bruno is a charismatic, devil-may-care hedonist who lives for the moment, while Roberto is cautious, introverted, and bound by convention. Despite their opposing personalities, Roberto finds himself drawn to Bruno's magnetic and liberating energy. The journey is a whirlwind of misadventures, impromptu visits to relatives, and encounters that peel back the layers of both characters, revealing Bruno's underlying failures and loneliness and awakening a new, reckless spirit within Roberto.

Core Meaning

Il Sorpasso is a masterful critique of Italy's 'economic miracle' of the early 1960s. Director Dino Risi uses the road trip as a metaphor to explore the seductive but ultimately hollow nature of the new consumerist society. The film contrasts the traditional, thoughtful Italy (represented by Roberto) with the modern, superficial, and fast-paced nation obsessed with status and immediate gratification (embodied by Bruno and his car). The core message is a cautionary one: the reckless pursuit of 'the easy life,' abandoning moral and personal responsibility, leads not to freedom but to tragedy. It is a poignant examination of a country losing its soul in a frantic, exhilarating, and ultimately destructive race toward modernity.

Thematic DNA

The Critique of the 'Economic Miracle'

The film serves as a powerful allegory for the social changes in Italy during its post-war economic boom. Bruno's character embodies the new Italian: materialistic, obsessed with appearances, and morally flexible, thriving in a society of newfound consumerism. The journey itself showcases a nation in transition, with new highways and booming coastal towns juxtaposed against fading traditions. Risi's portrayal is satirical and critical, suggesting that the rapid modernization came at the cost of cultural depth and moral integrity, leading to a spiritual emptiness masked by frantic energy.

The Duality of Freedom and Emptiness

Bruno represents a life of absolute freedom—unburdened by responsibility, constantly seeking pleasure and excitement. However, the film slowly reveals this freedom to be a facade for deep-seated loneliness, immaturity, and failure in his personal life, particularly with his estranged wife and daughter. His carefree existence is shown to be a frantic escape from his own shortcomings. Roberto is initially seduced by this 'easy life,' but the film's tragic conclusion serves as a stark commentary on the destructive potential of a life without substance or consequence.

Clash of Personalities and Generational Divide

The central dynamic of the film is the odd-couple pairing of Bruno and Roberto. Bruno is the fast-talking, charismatic embodiment of the present, while Roberto is the quiet, studious, and traditional past. Their journey is a microcosm of a generational and cultural clash. Roberto is initially appalled by Bruno's recklessness but is gradually corrupted by his charm, representing the seduction of an older, more thoughtful Italy by a newer, more superficial one. The film explores whether these two opposing forces can coexist or if one must inevitably destroy the other.

The Road Trip as a Journey of Self-Discovery

Like many road movies it inspired, Il Sorpasso uses the physical journey as a catalyst for internal transformation. Roberto, cooped up in his apartment, is forced out into the world and begins to shed his inhibitions, for better or worse. He learns to be more assertive and spontaneous, though he ultimately adopts Bruno's worst traits. Bruno, on the other hand, is forced to confront his past failures when they visit his ex-wife and daughter, revealing the tragic figure beneath the boisterous exterior. The road doesn't lead to enlightenment, but to a brutal revelation of character.

Character Analysis

Bruno Cortona

Vittorio Gassman

Motivation

Bruno is motivated by a desperate need to escape boredom, responsibility, and his own failures. His constant motion, talking, and pursuit of pleasure are a defense mechanism against introspection and the emptiness of his life. He seeks constant validation through seducing women, impressing strangers, and dominating the road, all to prop up a fragile ego.

Character Arc

Bruno appears static for most of the film, a force of nature who changes others but doesn't change himself. He starts as a charming, energetic, and irresponsible bon vivant and ends as the same man, albeit one who has now led someone to their death. However, the narrative subtly exposes the cracks in his facade. The visit to his ex-wife and daughter reveals him not as a carefree bachelor, but as a failed husband and father, full of regret and loneliness, masking his pain with relentless activity. His arc is one of revelation rather than transformation; the audience's perception of him deepens from an amusing rogue to a tragic, destructive figure.

Roberto Mariani

Jean-Louis Trintignant

Motivation

Roberto's primary motivation is a subconscious desire to break free from his constrained, lonely existence. He is drawn to Bruno because Bruno represents everything he is not: confident, spontaneous, and socially adept. He longs for experience, connection, and the 'easy life' that Bruno seems to lead, making him susceptible to his influence.

Character Arc

Roberto undergoes a significant and tragic transformation. He begins as a shy, studious, and repressed individual, confined to his room and his books. Initially hesitant and critical of Bruno's lifestyle, he is gradually seduced by its promise of freedom and excitement. He sheds his timidity, learns to drink, and attempts to be more assertive with women. His arc culminates in him embracing Bruno's recklessness completely, urging him to drive faster just before the fatal crash. He is corrupted and ultimately destroyed by the very lifestyle he sought to emulate, representing the vulnerability of tradition in the face of hollow modernity.

Lilli Cortona

Catherine Spaak

Motivation

Lilli is motivated by a desire for a stable life that her father never provided. Her engagement to Bibi is a pragmatic choice for security. While she still shows some affection for Bruno, her primary motivation is to build a future for herself, independent of his chaotic influence.

Character Arc

Lilli's arc is subtle but significant. As Bruno's daughter, she represents the consequence of his lifestyle and the next generation moving on without him. Her engagement to an older, wealthy man whom Bruno despises highlights Bruno's powerlessness and hypocrisy. She is not simply a rebellious teen but a young woman who has adapted to her father's absence by seeking stability, however imperfect. Her interactions with Bruno force him (and the audience) to see the human cost of his irresponsibility.

Symbols & Motifs

The Lancia Aurelia B24 Convertible

The car is the film's central symbol, representing the allure and danger of the new, modern Italy. It embodies speed, freedom, consumerism, and masculine virility. Initially a symbol of elegance, Bruno's modified, loud, and constantly speeding car represents the corruption of the Italian dream into something vulgar, obnoxious, and dangerous. It is both the vehicle of liberation for Roberto and the instrument of his death.

The car is a constant presence, the third main character of the film. The title itself, 'The Overtaking,' refers to Bruno's aggressive driving style. The customized, loud horn is used repeatedly to assert Bruno's dominance on the road. The car's ultimate crash off a cliff symbolizes the catastrophic end of the reckless pursuit of modernity that it represents.

The Via Aurelia (The Road)

The Via Aurelia, the coastal road they travel, symbolizes the path of modern life during the economic boom. It is a route of escape from the city and tradition, leading to seaside resorts that represent leisure and consumer culture. However, the road is also fraught with peril, and the constant, reckless 'sorpassi' (overtakings) mirror the cutthroat, competitive nature of the new society. The road offers the illusion of progress and freedom, but it ultimately leads to a dead end.

The entire film takes place along this road, from the empty streets of Rome on Ferragosto to the sunny beaches and, finally, to the treacherous cliffside curves of Tuscany where the journey ends tragically.

Ferragosto (August 15th Holiday)

The film's setting during Ferragosto, a major Italian summer holiday, symbolizes a time of societal pause and inversion. The empty city of Rome, described by Bruno as a 'graveyard,' creates a liminal space where the normal rules of life are suspended. This holiday atmosphere allows for the improbable encounter between Bruno and Roberto and facilitates their spontaneous, convention-defying journey. It represents a temporary, illusory escape from reality that must inevitably and tragically end.

The film opens on the morning of Ferragosto, with Bruno desperately searching for cigarettes and a phone in a deserted Rome. The two-day trip is contained within this holiday period, enhancing the dreamlike, and ultimately nightmarish, quality of the events.

Memorable Quotes

Ah Robbè, che te frega delle tristezze, lo sai qual è l'età più bella? Te lo dico io qual è. È quella che uno c'ha. Giorno per giorno. Fino a quanno schiatta se capisce.

— Bruno Cortona

Context:

Bruno says this to Roberto during their journey, trying to coax him out of his pensive and worried state of mind. It's a key moment where he articulates his core belief system, which stands in stark contrast to Roberto's life of careful planning and study.

Meaning:

Translation: 'Ah Robby, who cares about sadness? Do you know what the best age is? I'll tell you what it is. It's the one you have. Day by day. Until you kick the bucket, of course.' This line perfectly encapsulates Bruno's carpe diem philosophy. It is both his charismatic mantra and the justification for his reckless, irresponsible lifestyle, portraying life as a series of moments to be seized without thought for past or future.

Allora lo conosce bene: la prima impressione che si ha di lui è quella giusta.

— Gianna (Bruno's wife)

Context:

Gianna says this to Roberto after he admits he only met Bruno that morning. Her weary, cynical assessment punctures the mystique Bruno has built around himself throughout the trip.

Meaning:

Translation: 'Then you know him well: the first impression one has of him is the right one.' Spoken by Bruno's estranged wife, this line provides a crucial, sobering perspective on his character. It confirms to Roberto (and the audience) that Bruno's charismatic but shallow and unreliable surface is not a mask for hidden depths, but is, in fact, his true nature.

Sembra di essere in Inghilterra. / Per la campagna? / No, è che viaggiamo sempre sulla sinistra…

— Roberto Mariani / Bruno Cortona

Context:

This witty back-and-forth happens in the car as Bruno performs another one of his signature risky overtaking maneuvers ('il sorpasso'), a recurring motif throughout their journey.

Meaning:

Translation: 'It feels like being in England.' / 'Because of the countryside?' / 'No, because we're always driving on the left…' This exchange is a darkly comedic commentary on Bruno's dangerous driving. Roberto's dry observation highlights the constant risk Bruno takes by driving in the oncoming lane to overtake others, foreshadowing the tragic ending.

Philosophical Questions

Does true freedom lie in the rejection of all responsibility?

The film explores this through Bruno, who lives a life seemingly free from societal constraints, family ties, and long-term planning. His existence is a series of impulsive pleasures. However, the film systematically deconstructs this notion of freedom, revealing it as a source of profound loneliness, immaturity, and ultimately, destruction. It posits that a life devoid of responsibility is not freedom but a hollow, frantic escape that leaves a wake of emotional damage and, in this case, literal death.

What is the true cost of rapid societal modernization?

Il Sorpasso uses its characters and setting to question the uncritical celebration of the 'economic miracle.' It suggests that while modernization brings wealth, mobility (symbolized by the car), and new forms of leisure, it also fosters superficiality, moral decay, and a loss of community and tradition. Roberto's tragic fate serves as a metaphor for the destruction of the country's more thoughtful, humane past by a new, aggressive, and empty consumer culture.

Can fundamentally opposing natures truly connect, or does one inevitably consume the other?

The relationship between Bruno and Roberto is a study in contrasts. For a time, it seems a genuine, if unlikely, friendship is forming. Roberto is drawn to Bruno's vitality, and Bruno seems to enjoy the novelty of Roberto's earnestness. However, the film's conclusion suggests a predatory dynamic. Bruno's lifestyle doesn't just influence Roberto; it completely overwhelms and annihilates him. The film bleakly suggests that the reckless, vital force of modernity (Bruno) cannot coexist with the cautious, intellectual traditions of the past (Roberto) but must inevitably destroy it.

Alternative Interpretations

While the most common interpretation sees the ending as a moralistic condemnation of Bruno's hedonistic lifestyle, other readings exist. One perspective views the ending not as a punishment, but as a tragically logical outcome of the forces depicted. Roberto is not just a victim of Bruno, but of the societal shift that Bruno represents. His death symbolizes the death of an older, more contemplative Italy, which cannot survive the speed and recklessness of the new era. In this view, the film is less a simple morality tale and more a fatalistic tragedy about a nation's soul.

Another interpretation focuses on Roberto's agency. Instead of being purely a passive victim, Roberto actively chooses to embrace Bruno's world. His final cries for Bruno to go faster represent his full, albeit brief, liberation from his repressed self. His death, therefore, can be seen as the ultimate price of that liberation, a moment of intense, lived experience that his previous life could never offer. This reading frames the ending as more existentially complex, questioning whether a short, vibrant life is preferable to a long, unlived one.

Cultural Impact

Il Sorpasso is considered a masterpiece of Italian cinema and a cornerstone of the Commedia all'italiana (Comedy, Italian Style) genre. This genre blended humor with sharp social satire and often ended with a tragic or bitter twist, a departure from pure comedy. The film perfectly captured the zeitgeist of Italy during the 'miracolo economico' (economic miracle), a period of rapid industrialization and cultural change in the late 1950s and early 1960s. It masterfully depicted the anxieties, contradictions, and burgeoning consumerism of a nation hurtling towards modernity.

Initially dismissed by critics as cynical, the film was embraced by audiences who recognized its brazenly accurate portrait of Italian society. Over time, its critical stature grew immensely, and it is now hailed as a classic. Its influence on the road movie genre is significant, often cited as a precursor to films like Easy Rider (1969). The characters of Bruno and Roberto became archetypes, representing two conflicting sides of the Italian psyche. The film's title even became a political and economic term. Ultimately, Il Sorpasso provided a defining, tragicomic snapshot of a country at a historical crossroads, a commentary that remains relevant in its exploration of modernity and alienation.

Audience Reception

Initially, Il Sorpasso had a slow start, with only about fifty people attending its premiere. This was partly due to Vittorio Gassman's association with a recent box office failure. However, audiences quickly connected with the film's themes and characters. Through powerful word-of-mouth, it grew into a massive commercial success and a cultural touchstone in Italy. Spectators embraced the film's dark humor and its sharp, honest portrayal of Italian society, which contrasted with the more negative initial reviews from critics who found it cynical. Audiences loved the dynamic between Gassman and Trintignant and the film's exhilarating energy, even with its shocking and tragic ending. Over the decades, its popularity has endured, solidifying its status as a beloved classic of Italian cinema.

Interesting Facts

- The film initially had a rocky start at the box office, partly because its star, Vittorio Gassman, had just appeared in a major flop, Roberto Rossellini's 'Anima Nera'. However, word-of-mouth quickly turned it into a massive cultural phenomenon in Italy.

- The shocking, tragic ending was a point of contention. The film's producer, Mario Cecchi Gori, begged director Dino Risi to change it, fearing audiences would be turned off, but Risi, supported by screenwriter Rodolfo Sonego, insisted on keeping it.

- The term 'Il Sorpasso' (The Overtaking) entered the Italian lexicon to describe the moment in 1987 when Italy's economy metaphorically 'overtook' Britain's in terms of nominal GDP.

- Jean-Louis Trintignant, who was not well-known to the director, was cast as Roberto Mariani partly because Risi was looking for a young, blond actor of small stature to contrast with Gassman.

- The iconic car, a Lancia Aurelia B24, was not white as many assume from the black-and-white film, but actually a light blue.

- Director Dino Risi cheekily references his cinematic rival Michelangelo Antonioni. Bruno mentions he saw Antonioni's 'L'Eclisse' and it put him to sleep, a jab at the art-house director's reputation for slow, existential films and a meta-commentary on 'Il Sorpasso''s aim to entertain.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!