In the Mood for Love

花樣年華

"Feel the heat, keep the feeling burning, let the sensation explode."

Overview

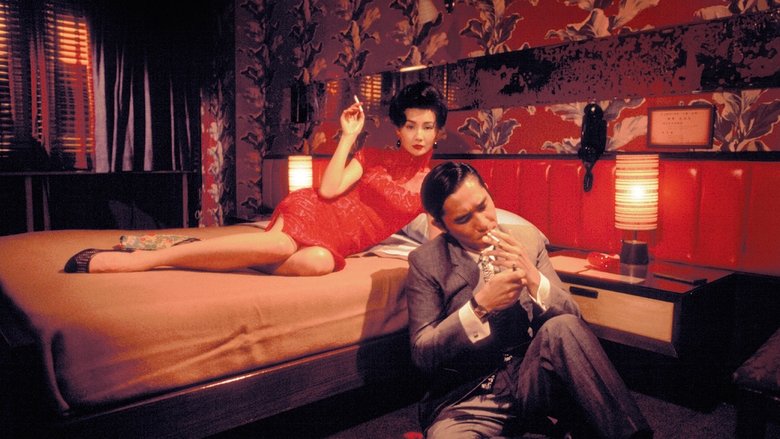

Set in the cramped and bustling Hong Kong of 1962, In the Mood for Love follows the intertwined lives of two neighbors, Su Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung) and Chow Mo-wan (Tony Leung). Both are married, and both of their spouses are frequently away on business trips. They move into adjacent apartments on the same day and maintain a polite but distant relationship.

Their solitary lives begin to intersect more frequently as they realize their respective partners are having an affair with each other. Drawn together by this shared betrayal, they form a unique and intimate bond, spending time together to role-play and understand how their spouses' affair might have begun. As they navigate their loneliness and the conservative social mores of their community, their own feelings for each other deepen, creating a poignant and restrained romance where much is left unsaid and undone.

Core Meaning

At its heart, In the Mood for Love is a profound meditation on the nature of memory, longing, and the agonizing beauty of what might have been. Director Wong Kar-wai was less interested in depicting a simple affair and more focused on exploring how individuals behave and relate to one another under the weight of secrets and societal expectations. The film poignantly captures the ephemeral nature of a particular time and place—1960s Hong Kong—and the quiet desperation of two souls who find solace in each other but are ultimately constrained by their circumstances and their own moral codes. It is a story about the love that exists in the spaces between glances, gestures, and unspoken words, a love that is perpetually 'in the mood' but never fully realized.

Thematic DNA

Unfulfilled Love and Longing

The central theme is the exploration of a profound but unconsummated love between Su Li-zhen and Chow Mo-wan. Their relationship is characterized by a deep sense of longing, restraint, and missed opportunities. They develop a powerful emotional intimacy but consciously decide not to replicate the actions of their unfaithful spouses, stating, "We won't be like them." This restraint, born out of a sense of morality and fear of social judgment, leads to a perpetually unresolved tension and a lingering feeling of what could have been.

Memory and Time

The film is structured like a memory, with a fragmented, non-linear narrative that emphasizes the subjective experience of time. Wong Kar-wai uses recurring musical motifs, slow-motion shots, and fades to create a dreamlike quality, suggesting that the events are being recalled from a nostalgic and perhaps unreliable perspective. The final intertitle, "He remembers those vanished years. As though looking through a dusty window pane, the past is something he could see, but not touch," encapsulates how the past is both vivid and intangible, a collection of moments that can be revisited but never changed.

Societal Norms and Repression

The characters' actions are heavily influenced by the conservative social environment of 1960s Hong Kong. The constant presence of gossiping neighbors and the strict moral codes of the time create an atmosphere of surveillance and judgment. This external pressure is a major factor in Su and Chow's decision to repress their feelings and conduct their relationship in secrecy. Their struggle highlights the conflict between personal desire and the need to maintain social propriety and honor.

Secrets and Betrayal

The narrative is built upon a foundation of secrets. The initial secret is the affair between their spouses, which Su and Chow uncover through subtle clues like a handbag and a tie. This discovery leads to the formation of their own secret relationship, which they shield from the prying eyes of their community. The film explores the emotional toll of keeping secrets and the complex ways in which betrayal can paradoxically bring two people together.

Character Analysis

Su Li-zhen Chan

Maggie Cheung

Motivation

Her primary motivation is to maintain her dignity and moral standing in the face of her husband's betrayal. While she yearns for the emotional connection she finds with Chow, she is equally motivated by a fear of social stigma and a powerful desire not to stoop to the level of their spouses. Her actions are driven by a complex interplay of loneliness, desire, and propriety.

Character Arc

Su Li-zhen begins as a poised, dutiful, and reserved secretary. Upon discovering her husband's infidelity, her composed exterior begins to crack. Her relationship with Chow Mo-wan awakens a deep longing within her, but she is constantly torn between her burgeoning feelings and her adherence to societal norms and her own moral code. She grapples with the desire for connection and the fear of becoming like her unfaithful husband, ultimately choosing a path of dignified restraint and quiet sorrow.

Chow Mo-wan

Tony Leung Chiu-wai

Motivation

Chow is motivated by a desire for companionship and an escape from the loneliness of his marriage. After discovering the affair, he seeks understanding and solace, which he finds in Su. His motivation evolves into a genuine love for her and a hope for a shared future, though he is ultimately unable to overcome the barriers that separate them.

Character Arc

Chow Mo-wan is a thoughtful and sensitive journalist who is deeply hurt by his wife's affair. Initially, his interactions with Su are a way to understand and process this betrayal. As their bond deepens, he becomes more willing to challenge social conventions and pursue a relationship with her. He is the one who more openly suggests they leave together, but he ultimately respects her hesitation. Years later, he is left with a profound sense of nostalgia and unresolved longing, which he symbolically buries at Angkor Wat.

Mrs. Suen

Rebecca Pan

Motivation

Her motivations are rooted in maintaining the social order and upholding the traditional values of her community. She is concerned with propriety and appearances, and her frequent interactions with Su serve as a constant reminder of the social scrutiny she is under.

Character Arc

Mrs. Suen is the landlady of Su Li-zhen's apartment. She is a friendly but intrusive figure who embodies the communal and gossipy nature of their Shanghainese community. She remains a constant presence, observing the comings and goings of her tenants and offering unsolicited advice, representing the societal pressures that Su and Chow must navigate.

Symbols & Motifs

Cheongsams (Qipaos)

Su Li-zhen's many beautiful and form-fitting cheongsams symbolize her state of mind, her elegance, and her confinement. The vibrant patterns and colors often contrast with her restrained demeanor, hinting at the passionate emotions she keeps hidden. The dresses also serve as a temporal marker, with their changing styles reflecting the passage of time and the evolution of her emotional journey.

Su wears a different cheongsam in almost every scene, each one meticulously chosen. The dresses are a constant visual focus, accentuating her graceful movements as she navigates the narrow corridors and stairways of her apartment building. They represent a kind of beautiful armor, presenting a composed exterior that masks her inner turmoil.

Clocks

Clocks are a recurring motif that underscores the themes of time, missed opportunities, and the characters' feeling of being trapped. The camera often lingers on clocks in Su's office or in their rooms, marking the slow passage of time and the minutes they spend waiting or apart. This persistent reminder of time's relentless march highlights the fleeting nature of their moments together.

Large clocks are prominently featured in the background of many scenes, particularly when Su and Chow are communicating. The visual emphasis on time creates a sense of pressure and foreshadows their eventual separation, highlighting how their potential future is slipping away with every tick.

Food and Dining

Shared meals, particularly trips to the noodle stall, represent the initial, tentative steps of Su and Chow's relationship. These moments of dining together offer them a brief respite from their loneliness and a space for their emotional connection to grow in a seemingly innocuous setting.

Initially, Su and Chow frequently pass each other on their solitary trips to buy noodles for dinner, highlighting their mutual loneliness. Later, they begin to share meals, and these scenes become central to their developing intimacy. The act of eating together becomes a substitute for the domestic companionship they lack in their marriages.

Room 2046

Room 2046, the hotel room where Chow writes his martial arts serials and where he and Su spend time together, becomes a sanctuary for their relationship, a private space away from the judging eyes of their neighbors. The number itself becomes significant, as it is the title of Wong Kar-wai's sequel, representing a place of memories and lost love.

Chow rents Room 2046 to have a quiet place to work with Su. It is within these walls that their bond deepens and they confront their feelings. The room is a liminal space where they can momentarily escape their realities. Chow later revisits the room, which has become a repository of his memories of Su.

Angkor Wat

The ancient temple of Angkor Wat serves as the final repository for Chow's unspoken secrets and unfulfilled love. Whispering his secret into a hole in the temple wall is a symbolic act of catharsis and eternal preservation. It allows him to unburden himself of his memories and feelings for Su, leaving them buried in the timeless ruins.

At the end of the film, Chow travels to Angkor Wat. He recalls an old fable about whispering a secret into a tree hollow and sealing it forever. He finds a cavity in the temple's stone wall, whispers into it, and plugs it with mud, signifying his decision to entomb his love and memory of Su, letting go of the past while ensuring it is never truly forgotten.

Memorable Quotes

It is a restless moment. She has kept her head lowered... to give him a chance to come closer. But he could not, for lack of courage. She turns and walks away.

— Opening Title Card

Context:

This quote appears on screen at the very beginning of the film, setting the emotional stage for the narrative that is about to unfold.

Meaning:

This opening text establishes the central theme of the film: missed opportunities and unspoken feelings. It immediately sets a tone of longing and hesitation that defines the entire relationship between Su and Chow, foreshadowing their ultimate inability to act on their love.

He remembers those vanished years. As though looking through a dusty window pane, the past is something he could see, but not touch. And everything he sees is blurred and indistinct.

— Closing Title Card

Context:

This text is shown at the very end of the film, after Chow has whispered his secret into the wall at Angkor Wat, providing a final, poignant reflection on the nature of his memories.

Meaning:

This closing statement encapsulates the film's exploration of memory. It reinforces the idea that the past, while accessible in thought, is forever out of reach. It perfectly describes Chow's final state of mind—living with the beautiful but hazy and untouchable memories of his time with Su.

In the old days, if someone had a secret they didn't want to share... they went up a mountain, found a tree, carved a hole in it, and whispered the secret into the hole. Then they covered it with mud. And leave the secret there forever.

— Chow Mo-wan

Context:

Chow shares this story with his friend Ah Ping before he travels to Angkor Wat. It foreshadows the film's final, symbolic act at the temple.

Meaning:

This quote introduces the ancient ritual that Chow later adopts to deal with his unexpressed love for Su. It speaks to the burden of carrying a powerful secret and the deep human need for catharsis and a way to preserve something sacred and painful without having to speak it aloud to another person.

I didn't know married life would be so complicated. When you're single, you are only responsible to yourself. Once you're married, doing well on your own is not enough.

— Su Li-zhen Chan

Context:

Su says this to Chow during one of their conversations where they reflect on their lives and what might have been if they hadn't married.

Meaning:

This line reveals Su's disillusionment with marriage and the weight of responsibility she feels. It reflects the societal expectations placed upon married individuals at the time and highlights the loss of personal freedom that both she and Chow experience, which contributes to their shared sense of entrapment.

Philosophical Questions

Is love a choice or an uncontrollable feeling?

The film delves into this question by presenting two characters who develop a powerful, seemingly inevitable emotional connection. However, they consistently make the conscious choice not to act on their feelings in a physical sense. Their story suggests that while the 'mood for love' may arise uncontrollably, the actions one takes are a matter of moral and personal choice, shaped by duty, fear, and circumstance.

Can one truly know the past, or is memory just a subjective reconstruction?

Through its fragmented narrative, recurring motifs, and final, poignant statement about memory, the film argues that the past is not an objective reality but a deeply personal, emotional landscape. The story is presented as a recollection, 'blurred and indistinct,' suggesting that memory is selective, colored by longing and regret. The past is something that can be felt and revisited in the mind, but never truly grasped or changed.

What is the relationship between personal desire and societal responsibility?

In the Mood for Love places the intense personal desires of Su and Chow in direct conflict with the strict social expectations of their community. Their struggle illustrates the immense pressure of conformity and the personal sacrifices made to maintain one's honor and social standing. The film asks whether adherence to a moral code, even when it leads to personal unhappiness, is a form of strength or a tragic concession to external pressures.

Alternative Interpretations

While the film's central narrative is clear, its ambiguous nature, particularly the ending, invites several interpretations.

A Platonic Relationship: The most common interpretation is that Su and Chow's relationship remains platonic. They consciously choose not to consummate their feelings out of a sense of moral duty, determined not to become like their cheating spouses. Their bond is one of deep emotional intimacy and shared sorrow, but not physical infidelity. The film's power, in this reading, comes from their noble and painful restraint.

An Unseen Affair: Some critics and viewers speculate that an affair does happen, but it occurs off-screen, consistent with Wong Kar-wai's style of omitting key narrative events. The rehearsals and the intimate moments in Room 2046 could be seen as blurring the line between role-playing and reality. This interpretation suggests that their statement, "We won't be like them," is more of a hopeful denial than a statement of fact.

A Fantasy of Love: Another perspective is that the relationship is more of a shared fantasy. Traumatized by betrayal, Su and Chow create an idealized romance to cope with their pain and loneliness. They fall in love with the idea of each other and the roles they play, rather than the reality. Their inability to be together in the real world stems from the fact that their connection is rooted in a shared, imagined space, making a real-life commitment impossible.

The Ending as Metaphor: Chow's final act at Angkor Wat can be interpreted in different ways. Is he burying his love forever to move on, or is he preserving it in a sacred place, acknowledging its eternal significance? The ambiguity leaves the audience to decide whether the ending is one of tragic finality or poignant preservation.

Cultural Impact

In the Mood for Love had a profound cultural impact, solidifying Wong Kar-wai's status as a leading auteur of international cinema and influencing a generation of filmmakers, including Sofia Coppola and Barry Jenkins. Upon its release, it was hailed as a masterpiece and is consistently ranked among the greatest films of the 21st century and of all time.

Historical Context: The film is set in 1960s Hong Kong, a period of significant social and political transition. It captures the world of Shanghainese émigrés who fled to the British colony after the rise of Communism in mainland China. This community, with its own dialects, traditions, and sense of displacement, forms the backdrop for the characters' personal dramas. The film's ending in 1966 also subtly alludes to the looming Cultural Revolution in China and the 1967 riots in Hong Kong, adding a layer of historical melancholy to the personal narrative.

Influence on Cinema and Fashion: The film's distinct visual aesthetic—characterized by its saturated color palette, slow-motion cinematography, and meticulous framing—has been widely imitated. Its unique portrayal of repressed desire and unspoken romance offered a powerful alternative to more explicit love stories. Beyond cinema, the film had a significant impact on fashion, popularizing the cheongsam (or qipao) and cementing its status as an iconic and elegant garment. The film's overall mood and style have influenced everything from music videos to high fashion.

Critical and Audience Reception: The film was met with widespread critical acclaim, winning the Best Actor award for Tony Leung at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival. Critics praised its stunning visuals, emotional depth, and masterful direction. Audiences were captivated by its beauty and its poignant story of unfulfilled love, and it remains a beloved classic in art-house cinema circles worldwide.

Audience Reception

In the Mood for Love received overwhelmingly positive reactions from both critics and audiences, and is widely regarded as a cinematic masterpiece. On Rotten Tomatoes, it holds a 92% approval rating, with the consensus praising it as an 'exquisitely shot showcase... that's liable to break your heart.' Metacritic assigned it a score of 87 out of 100, indicating 'universal acclaim.'

Praised Aspects: Viewers and critics alike lauded the film's stunning cinematography, meticulous production design, and evocative use of color and music. The performances of Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung were universally acclaimed for their subtlety and emotional depth. Many praised the film's mature and nuanced exploration of love and longing, finding its restraint more powerful than explicit romantic depictions.

Points of Criticism: The primary criticism from some viewers centered on the film's slow, deliberate pace and its non-linear, impressionistic narrative. Some found the plot to be minimal and the lack of a conventional romantic resolution to be frustrating or unsatisfying. The repetitive use of the main musical theme was also a point of irritation for a minority of viewers.

Overall Verdict: Despite minor criticisms regarding its pacing, the vast majority of audiences found In the Mood for Love to be a deeply moving, beautiful, and unforgettable cinematic experience. Its reputation has only grown over time, and it is cherished by film lovers for its artistry and emotional resonance.

Interesting Facts

- The film's English title was inspired by the song 'I'm in the Mood for Love' by Bryan Ferry. The original Chinese title, 'Huāyàng Niánhuá', translates to 'Flowery Years' or 'Age of Blossoms'.

- Director Wong Kar-wai is famous for shooting without a finished script, preferring to improvise with the actors on set. This led to a lengthy 15-month shoot for the film.

- The initial shooting location was planned for Beijing, but due to the director's improvisational style and potential political sensitivities, the production was moved to Macau and Bangkok to replicate the look of 1960s Hong Kong.

- Maggie Cheung wore over 20 different elegant cheongsams in the final cut of the film, with a total of 46 being made for the production. These dresses became iconic and crucial to the film's visual identity.

- The film is the second installment in an informal trilogy by Wong Kar-wai, preceded by 'Days of Being Wild' (1990) and followed by '2046' (2004), which further explores themes of love, memory, and time.

- The story was originally inspired by a Japanese short story about two strangers who frequently pass each other on a stairwell without speaking.

- Wong Kar-wai and his cinematographers, Christopher Doyle and Mark Lee Ping-bing, often shot in real, cramped apartments to achieve the film's claustrophobic and intimate atmosphere.

Easter Eggs

On some DVD and Blu-ray releases of the film, there is a hidden music video featuring Tony Leung.

This is a small, hidden gem for dedicated fans of the film and the actor, offering a rare, out-of-character glimpse of Tony Leung. It's an example of the kind of playful secret that physical media sometimes holds.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!