The Elephant Man

"A true story of courage and human dignity."

Overview

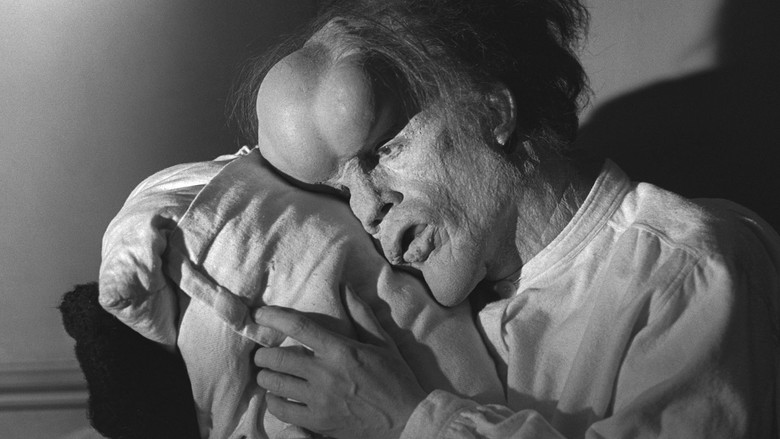

Set in Victorian London, "The Elephant Man" chronicles the true story of John Merrick (named Joseph in real life), a man suffering from severe physical deformities. Initially exhibited as a sideshow freak by a cruel ringmaster, Mr. Bytes, Merrick is discovered by Dr. Frederick Treves, a compassionate surgeon at the London Hospital. Treves brings Merrick to the hospital, at first for scientific study, but soon discovers a gentle, intelligent, and dignified soul hidden beneath the shocking exterior.

As Treves introduces Merrick to London's high society, John experiences kindness and acceptance for the first time, befriending a famous actress, Madge Kendal. However, his newfound peace is fragile. The film explores the spectrum of human reaction to Merrick—from revulsion and exploitation to empathy and admiration. It navigates themes of inner versus outer beauty, the nature of humanity, and whether societal kindness is a form of charity or just a more refined form of spectacle.

Core Meaning

The core meaning of "The Elephant Man" is a profound exploration of human dignity and the essence of humanity itself. Director David Lynch poses the question: What defines a man? Is it his appearance or the quality of his soul? The film argues that true humanity lies not in physical form but in kindness, intelligence, creativity, and the capacity for love. It serves as a powerful critique of a society that judges, fears, and exploits what it doesn't understand, contrasting the cruelty of the mob with the quiet grace of a man who, despite immense suffering, never loses his gentle spirit. Ultimately, the film is a testament to the idea that love and acceptance are what make life truly full and meaningful.

Thematic DNA

Humanity and Dignity

The central theme is the search for dignity in the face of dehumanizing cruelty. John Merrick, despite being treated as a monster, consistently demonstrates grace, intelligence, and sensitivity. His famous cry, "I am not an animal! I am a human being!" encapsulates this struggle. The film forces the audience and the characters to look past his physical form and recognize the profound humanity within, questioning who the real "monsters" are: the disfigured man or his cruel tormentors.

Exploitation vs. Compassion

The film presents a spectrum of human behavior, from the blatant, cruel exploitation by his 'owner' Bytes and the night porter Jim, to the more complex motivations of Dr. Treves. Treves initially sees Merrick as a subject for medical advancement and fame but evolves to feel genuine compassion and friendship. This theme questions the nature of charity itself, as even the high-society visitors who shower Merrick with attention may be using him as a fashionable curiosity, a more civilized form of a freak show.

Appearance vs. Reality

This classic theme is at the heart of the narrative. Merrick's grotesque exterior conceals a beautiful, artistic, and gentle soul. Conversely, the supposedly civilized Victorian society is shown to have a dark, cruel underbelly. The film constantly challenges the viewer's prejudices, suggesting that true ugliness lies in malice and inhumanity, not in physical deformity. Mrs. Kendal's ability to see Merrick as "a Romeo" is a pivotal moment in recognizing his inner self.

Loneliness and Belonging

Merrick suffers from profound isolation due to his condition. His entire life has been spent hidden or as an object of scorn. His time at the hospital is his first experience of community and belonging. The simple acts of being spoken to with kindness, shaking a hand, or receiving a gift become monumental events. His construction of the cathedral symbolizes his attempt to build a connection to something beautiful and permanent, a sanctuary for his isolated soul.

Character Analysis

John Merrick

John Hurt

Motivation

His primary motivation is to be seen and treated as a human being. He yearns for love, connection, and normalcy. He treasures the picture of his beautiful mother, hoping that she could one day love him as he is, and strives to be a "good man" to be worthy of that love.

Character Arc

Merrick's journey is one of profound transformation from an object of horror and pity to a recognized human being. Initially presented as a mute and brutish "freak," he slowly reveals his intelligence, sensitivity, and gentle nature under the care of Dr. Treves. He moves from a life of constant abuse and isolation to experiencing friendship, art, and acceptance, culminating in a moment of public dignity before he chooses to die peacefully. His arc is about reclaiming the personhood that was denied to him his entire life.

Dr. Frederick Treves

Anthony Hopkins

Motivation

Initially, his motivation is a mix of scientific ambition and genuine humanitarian concern. This evolves into a deep-seated need to protect Merrick and provide him with the dignity and life he was denied. He becomes Merrick's primary advocate and friend.

Character Arc

Dr. Treves begins as an ambitious Victorian surgeon, initially motivated by scientific curiosity and the potential for professional renown that Merrick represents. As he comes to know Merrick, his clinical detachment gives way to genuine compassion, friendship, and a sense of protective duty. However, he grapples with guilt, questioning whether his actions are truly for Merrick's benefit or if he has simply created a more sophisticated freak show for high society, asking himself, "Am I a good man? Or a bad man?".

Madge Kendal

Anne Bancroft

Motivation

Her motivation is empathy and an artist's ability to see deeper truths. She recognizes Merrick's love for theater and literature and connects with him on an intellectual and emotional level, treating him as an equal and a friend.

Character Arc

Mrs. Kendal is an accomplished stage actress who is introduced to Merrick by Treves. Initially visiting out of curiosity, she is the first person from high society to treat Merrick not with pity, but with genuine warmth and normalcy. Her arc is one of breaking social barriers. She sees past his appearance to the romantic soul within, famously calling him "a Romeo." Her friendship is instrumental in opening the floodgates of social acceptance for Merrick.

Mr. Bytes

Freddie Jones

Motivation

His sole motivation is greed. He profits from Merrick's misery and is enraged when Treves takes away his "attraction." He embodies the base, inhuman cruelty that Merrick has suffered his entire life.

Character Arc

Mr. Bytes is a static character who represents the cruelest, most exploitative segment of society. He is Merrick's "owner" in the freak show and sees him only as a source of income, treating him with brutal violence and complete disregard for his humanity. He never changes, reappearing later in the film to kidnap Merrick and return him to a life of misery, demonstrating that such cruelty is persistent and unrepentant.

Mrs. Mothershead

Wendy Hiller

Motivation

Her primary motivation is maintaining order and ensuring the proper running of the hospital. This evolves into a deep, maternal sense of duty and care for Merrick's well-being, valuing his safety and dignity above social conventions.

Character Arc

As the head matron of the hospital, Mrs. Mothershead is initially stern and pragmatic, concerned with rules and propriety. She is skeptical of the attention Merrick receives, seeing it as a disruption and a form of voyeurism. Over time, she witnesses Merrick's gentle nature and the genuine kindness he inspires, and her stern demeanor softens into fierce protectiveness. She becomes one of his most steadfast guardians, defending him from the abusive night porter.

Symbols & Motifs

The Cathedral Model

The model of the cathedral that Merrick builds represents his own soul, his quest for grace, and his creation of beauty and order out of a life of chaos and suffering. It is an "imitation of grace flying up and up from the mud." As he builds it, his own social and inner world becomes more complete. Its completion coincides with his feeling of final acceptance, allowing him to find peace.

Merrick sees the spires of a cathedral from his hospital window and dedicates himself to recreating it. The progress of the model often mirrors his own journey toward acceptance. When he is abused by the night porter, the model is disturbed. He finishes it just before his death, after attending the theatre and receiving a standing ovation, signifying that his life's work of being seen as human is complete.

The Hood and Mask

The hood and mask that Merrick wears symbolize his forced alienation from society. They are tools to hide his appearance and make him palatable for public view, effectively erasing his identity to prevent others' discomfort. When the mob tears it from him at the train station, it is a violent stripping of his last defense, forcing him into the open to be judged.

Dr. Treves first provides Merrick with a hood and cap to travel to and from the hospital without causing a scene. Merrick is constantly seen under some form of covering in public. The most dramatic use is at the Liverpool Street Station, where he is cornered by a mob and his hood is torn off, leading to his desperate cry, "I am not an animal!".

Industrial Machinery

The recurring imagery of smokestacks, steam, and harsh industrial machinery represents the oppressive, dehumanizing forces of Victorian society. This industrial world is as uncaring and monstrous as the mobs that torment Merrick. Lynch visually links the explosive, uncontrolled growth of Merrick's tumors to the chaotic, powerful, and often destructive nature of the industrial revolution. Dr. Treves even remarks, "Abominable things these machines—you can't reason with them."

The film is filled with shots of factories, loud machinery, and smoke. The sound design often incorporates industrial noises, creating an atmosphere of dread and oppression. This imagery contrasts sharply with the quiet, gentle moments of human connection Merrick experiences in his room.

Mirrors and Reflections

Mirrors symbolize self-awareness, identity, and the horror of Merrick's own condition. For most of his life, he has been shielded from his own reflection. When confronted with it, he is frightened not just by his appearance, but by the confirmation of how the world sees him. It represents the inescapable reality of his physical self.

In a key scene, the cruel night porter, Jim, forces a mirror in front of Merrick's face, a moment of profound psychological abuse. His fear of his own reflection is one of his deepest terrors, mentioned alongside the trauma of his mother's supposed accident with an elephant. This contrasts with how others serve as mirrors for him; through their kindness, he begins to see a reflection of a worthy human being.

Memorable Quotes

I am not an elephant! I am not an animal! I am a human being! I... am... a man!

— John Merrick

Context:

After escaping from Bytes on the continent, Merrick makes his way back to London. At Liverpool Street Station, he is accidentally knocked down, and his hood falls off, revealing his face to the public. A horrified crowd chases him and corners him in a men's lavatory, where he collapses and screams this line before being rescued.

Meaning:

This is the film's most iconic and powerful line. It is Merrick's desperate, passionate assertion of his own humanity in the face of a terrifying mob that sees him only as a monster. It's the central thesis of the film, a cry for dignity and recognition that defines his entire struggle.

My life is full because I know I am loved.

— John Merrick

Context:

Merrick says this to Dr. Treves in a quiet moment in his hospital rooms. After months of care, friendship, and visits from London society, he reflects on his newfound happiness, showing that the kindness he has received has fundamentally changed his existence.

Meaning:

This quote reveals that Merrick's ultimate measure of a successful life is not a cure or a change in his physical state, but the feeling of being loved and accepted. It shows his profound understanding of what is truly important and highlights his incredible capacity for gratitude despite his immense suffering.

People are frightened by what they don't understand.

— John Merrick

Context:

Merrick says this during a visit from a wealthy couple from high society. He is explaining, with eloquence, why people have treated him so poorly throughout his life, impressing his visitors with his wisdom and lack of resentment.

Meaning:

This line showcases Merrick's profound intelligence and empathy. Rather than expressing bitterness, he offers a philosophical and forgiving explanation for the cruelty he has endured. He understands that people's fear and hatred come from ignorance, a remarkably insightful and compassionate perspective.

Am I a good man? Or a bad man?

— Dr. Frederick Treves

Context:

Dr. Treves poses this question to his wife, Ann, in the privacy of their home. He is plagued by self-doubt after Mrs. Mothershead accuses him of using Merrick as a spectacle, just like the freak show.

Meaning:

This question reveals Dr. Treves's central moral conflict. He worries that by bringing Merrick into the hospital and introducing him to society, he has not saved him but merely exchanged one form of exhibition for another, more refined one. He questions his own motives, wondering if he is acting out of pure compassion or a selfish desire for fame.

Oh, Mr. Merrick, you're not an elephant man at all... You're a Romeo.

— Madge Kendal

Context:

During her first visit to Merrick's rooms, Mrs. Kendal brings him a copy of Romeo and Juliet. They recite lines together, and she is so moved by his sensitivity and gentle nature that she makes this declaration, kissing him on the cheek and solidifying their friendship.

Meaning:

This is a pivotal moment of acceptance and understanding. Mrs. Kendal, a professional actress, looks past Merrick's deformities and sees the romantic, sensitive soul who loves Shakespeare. She gives him a new name, one associated with love and poetry, directly contradicting the dehumanizing label he has carried his whole life.

Philosophical Questions

What is the true nature of humanity?

The film relentlessly explores whether humanity is defined by outward appearance or inner qualities. It contrasts John Merrick, who is physically monstrous but embodies kindness, intelligence, and grace, with characters who are physically "normal" but act with monstrous cruelty and prejudice. The film suggests that core human virtues like empathy, creativity, and the capacity to love are the true measures of a person, forcing the audience to question their own criteria for judging others.

What are the ethics of 'helping'?

Through Dr. Treves, the film examines the fine line between compassion and exploitation. Treves rescues Merrick from abject cruelty, but in doing so, he also makes him a subject of medical study and a spectacle for London's elite. The film raises questions about the motivations behind charity and care. Is it truly for the benefit of the afflicted, or does it also serve the ego and reputation of the benefactor? Mrs. Mothershead's accusation that Treves is still running a freak show, just with a "better class of people," crystallizes this dilemma.

Can one find beauty and purpose in profound suffering?

Merrick's life is one of almost unimaginable suffering, yet he is not portrayed as merely a victim. He is a creator, an artist who builds the beautiful cathedral model. He has a deep appreciation for literature, art, and religion. The film explores the idea that even in the darkest circumstances, the human spirit can find and create beauty. Merrick's gentle nature and lack of bitterness suggest a capacity for grace that transcends his physical pain, posing the question of whether suffering can lead to a deeper understanding of life's meaning.

Alternative Interpretations

While the primary interpretation of "The Elephant Man" is a humanistic drama about dignity, some critical analyses offer alternative readings. One perspective focuses on the character of Dr. Treves, viewing the film as much about his moral crisis as Merrick's plight. In this interpretation, Treves's journey is a critique of the Victorian medical establishment and its potential for exploitation under the guise of scientific inquiry and charity. His self-doubt suggests he is never fully free from the impulse to use Merrick for his own ends, whether for fame or for a sense of moral self-worth.

Another interpretation views the film's ending through a more ambiguous lens. Merrick's decision to lie down to sleep, knowing it will likely kill him, can be seen not just as a peaceful acceptance of death but as an act of suicide. Having finally achieved a moment of perfect acceptance and normalcy after the theatre, he may believe that this is the peak of his existence and that life can only return to suffering. In this reading, his final act is a tragic but autonomous choice to end his life on his own terms, preserving the perfection of that moment.

Cultural Impact

"The Elephant Man" was a critical and commercial success upon its release in 1980, earning eight Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture. Its impact was immediate and significant. The film's most direct influence was on the Academy Awards themselves; the outcry over Christopher Tucker's groundbreaking makeup being ineligible for an award led to the creation of the Best Makeup and Hairstyling category in 1981. The film solidified David Lynch's reputation, proving he could masterfully direct a narrative, character-driven drama in addition to the surrealist work of "Eraserhead." It is often considered his most accessible film.

Culturally, the film brought the tragic story of Joseph Merrick to a global audience, sparking widespread interest in his life and condition. It has become a timeless statement on dignity, prejudice, and the nature of humanity, and is frequently studied in film, ethics, and medical humanities courses. The phrase "I am not an animal, I am a human being" has entered the cultural lexicon as a powerful plea for dignity. The film's striking black-and-white cinematography by Freddie Francis and its blend of historical drama with Lynch's signature atmospheric and unsettling sound design have been praised and influential.

Audience Reception

Audiences have overwhelmingly praised "The Elephant Man" as a deeply moving and powerful masterpiece. Viewers consistently highlight the heartbreaking performance by John Hurt, who masterfully conveys immense emotion and humanity from beneath layers of heavy makeup, and the nuanced portrayal of Dr. Treves by Anthony Hopkins. David Lynch's direction is frequently lauded for its sensitivity, artistic vision, and the haunting atmosphere created by the black-and-white cinematography and industrial soundscape. Many viewers find the film to be an emotionally shattering but ultimately beautiful and life-affirming experience. The central theme of looking beyond outward appearances to find inner beauty resonates strongly, and the famous "I am not an animal" scene is cited as one of cinema's most powerful moments. Criticism is rare, but some viewers find the film's depiction of cruelty and suffering to be intensely difficult to watch, and a minority have found its sentimentality to be heavy-handed. Overall, it is regarded as a timeless classic that evokes profound empathy and reflection on human dignity.

Interesting Facts

- Executive producer Mel Brooks deliberately kept his name off the credits to prevent audiences from mistakenly thinking the film was a comedy.

- The intricate makeup for John Merrick, designed by Christopher Tucker, took seven to eight hours to apply each day and was based on actual casts of Joseph Merrick's body from the Royal London Hospital's museum.

- The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences received so many complaints about the film's lack of recognition for its makeup effects that they created the permanent category for Best Makeup the following year.

- John Hurt, who played Merrick, found the makeup process so grueling that he once told his girlfriend, "I think they have finally managed to make me hate acting." He worked on alternate days to cope with the strain.

- The film's script originated with a babysitter who gave it to producer Jonathan Sanger, who was then Mel Brooks's assistant director.

- David Lynch was hired to direct after Mel Brooks watched his debut feature, the surreal and bizarre "Eraserhead," and loved it.

- In real life, the man's name was Joseph Merrick, not John Merrick. The name was misprinted in Dr. Treves's memoirs, and the error was carried over into the film.

- The actor who plays an alderman in the film is named Frederick Treves, the real-life great-nephew of the doctor who cared for Merrick.

- During a lengthy production delay on the film "Heaven's Gate," John Hurt flew back to England, filmed all his scenes for "The Elephant Man," and then returned to the set of "Heaven's Gate."

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!