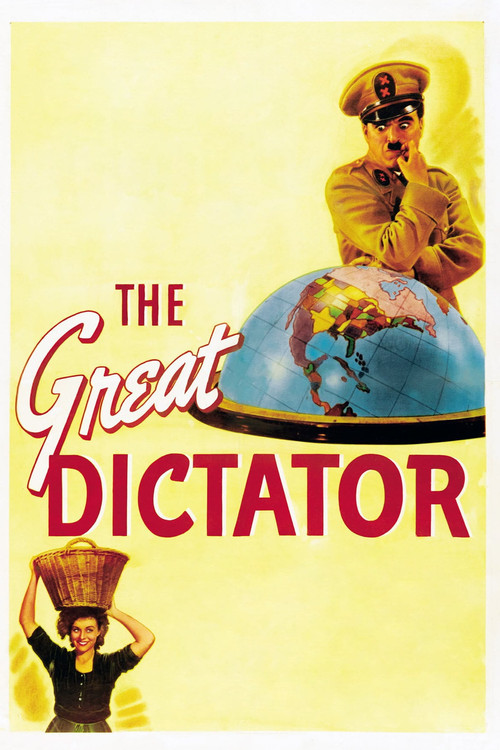

The Great Dictator

"Once again - the whole world laughs!"

Overview

"The Great Dictator" is Charlie Chaplin's first true sound film, a bold and controversial political satire released in 1940, before the United States had entered World War II. Chaplin stars in a dual role, portraying both a ruthless, power-hungry dictator, Adenoid Hynkel, a clear parody of Adolf Hitler, and a humble Jewish barber who is a veteran of World War I suffering from amnesia. The film cleverly intercuts between the grandiose, absurd world of the dictator and the persecuted, everyday life within the Jewish ghetto.

The story follows the Jewish barber as he returns to his shop after years in a military hospital, unaware of the drastic political changes and the brutal persecution of Jews under Hynkel's regime. He befriends and falls for his neighbor, Hannah, and together they attempt to resist the stormtroopers. Meanwhile, Dictator Hynkel is focused on his plans for world domination, comically depicted in his interactions with his advisors and his rival dictator, Benzino Napaloni of Bacteria. Through a case of mistaken identity, the barber is eventually mistaken for Hynkel, leading to a powerful and unexpected climax.

Core Meaning

"The Great Dictator" is a powerful condemnation of fascism, antisemitism, and Nazism, made at a time when such a direct critique was a significant political risk. The film's core message is a plea for humanity, peace, and democracy in the face of tyranny and hatred. Chaplin uses satire to expose the absurdity and dangers of totalitarianism, stripping away the aura of power to reveal the pathetic and insecure nature of dictators. The film culminates in a direct and impassioned speech where Chaplin, breaking character, addresses the audience directly, advocating for unity, kindness, and the power of the people to create a better world. It's a call to action, urging individuals to resist oppression and fight for a life of freedom and beauty.

Thematic DNA

The Absurdity of Power and Tyranny

Chaplin masterfully satirizes the megalomania of dictators. Adenoid Hynkel is portrayed not as a formidable leader but as a comically insecure and infantile figure. His nonsensical, guttural speeches, his balletic dance with a globe balloon, and his petty rivalry with Benzino Napaloni all serve to demystify and ridicule the nature of absolute power. The film suggests that behind the terrifying facade of fascism lies a fragile and ludicrous ego.

Humanity vs. Inhumanity

The film starkly contrasts the warmth and resilience of the Jewish ghetto community with the cold, mechanized brutality of Hynkel's regime. The Jewish barber represents the common man, capable of love, kindness, and courage in the face of persecution. This theme is most powerfully conveyed in the final speech, which champions human qualities like kindness, gentleness, and universal brotherhood over the machine-like thinking of dictators.

The Power of the People

A central message of the film is that power ultimately resides with the people. The final speech is a direct appeal to the masses to recognize their own strength and unite against oppression. Chaplin argues that dictatorships are a temporary perversion and that the will of the people for freedom and a decent life will eventually prevail. It's a call for global solidarity and a reminder that individuals are not powerless against tyrannical regimes.

Persecution and Resilience

"The Great Dictator" was one of the first mainstream films to directly address the persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany. It portrays the fear, violence, and injustice faced by the Jewish community in the ghetto. However, it also highlights their resilience, their ability to find moments of joy and humor, and their courage in resisting oppression, as seen in the character of Hannah.

Character Analysis

A Jewish Barber

Charlie Chaplin

Motivation

His primary motivations are survival, love for Hannah, and a fundamental sense of decency and kindness. He simply wants to live a peaceful life but is forced by circumstance to confront evil.

Character Arc

The barber begins as a naive and amnesiac victim, unaware of the political horrors that have consumed his country. As he experiences the brutality of the regime and falls in love with Hannah, he is moved to small acts of defiance. His journey culminates in an extraordinary moment where, mistaken for the dictator, he finds his voice and delivers a powerful speech for humanity, transforming from a passive victim into an active and courageous advocate for freedom.

Adenoid Hynkel

Charlie Chaplin

Motivation

His sole motivation is the acquisition of absolute power and world domination. He is driven by narcissism, hatred, and a deep-seated insecurity that manifests in his bombastic speeches and temper tantrums.

Character Arc

Hynkel is a static character, remaining a power-mad, insecure, and ridiculous figure throughout the film. He does not grow or change but instead serves as a consistent object of satire. His arc is one of escalating ambition, from persecuting Jews to planning the invasion of neighboring countries, which is ultimately thwarted by his own buffoonery when he is mistaken for the barber and arrested.

Hannah

Paulette Goddard

Motivation

Hannah is motivated by a desire for a better, more just world. She fights for her dignity and the safety of her community, and she embodies the spirit of hope that persists even in the darkest of times.

Character Arc

Hannah is a resilient and defiant resident of the ghetto. She maintains her hope and spirit despite the persecution. Initially a fighter who stands up to the stormtroopers, she is forced to flee with her family. Her journey represents the plight of refugees. The film ends with her listening to the barber's speech on the radio, her face turning towards the sunlight in a final image of hope.

Benzino Napaloni

Jack Oakie

Motivation

Much like Hynkel, Napaloni is motivated by ego and a desire to project an image of strength and power. His main goal in the film is to outmaneuver and upstage Hynkel during their meeting.

Character Arc

Napaloni is the bombastic and boisterous dictator of Bacteria, a parody of Benito Mussolini. He serves as a comic foil to Hynkel, and their interactions are a satirical depiction of the fragile egos and power plays between dictators. He is a static character whose purpose is to further ridicule the nature of fascist leaders.

Symbols & Motifs

The Globe Balloon

The globe balloon symbolizes Hynkel's narcissistic and childish desire for world domination. His graceful, almost loving dance with it represents his dream of possessing the world, treating it as a personal plaything. The eventual bursting of the balloon is a powerful visual metaphor for the fragility and ultimate futility of his ambitions.

In a famous and largely silent sequence, Adenoid Hynkel performs an ethereal ballet with a large, inflatable globe in his office, set to the prelude of Wagner's "Lohengrin." His fantasy is shattered when the balloon pops in his hands.

The Double Cross

The symbol of Hynkel's party, the "double cross," is a thinly veiled and satirical representation of the Nazi swastika. The name itself implies betrayal and deception, reflecting Chaplin's view of the fascist regime's promises and ideology.

The double cross emblem is prominently displayed throughout the film on uniforms, flags, and buildings in Tomainia, visually establishing the oppressive regime.

Mistaken Identity

The identical appearance of the Jewish barber and the dictator Hynkel is the film's central plot device and a powerful symbol. It highlights the arbitrary nature of power and identity, suggesting that the positions of the oppressor and the oppressed could easily be reversed. It also serves as a commentary on the shared humanity (or potential for inhumanity) that exists in everyone. Charles Chaplin Jr. quoted his father as saying, "he's the madman, I'm the comic. But it could have been the other way around."

The physical resemblance between the two characters, both played by Chaplin, drives the narrative, leading to the climactic moment where the barber is forced to give a speech in Hynkel's place.

Memorable Quotes

I'm sorry, but I don't want to be an emperor. That's not my business. I don't want to rule or conquer anyone. I should like to help everyone - if possible - Jew, Gentile - black man - white.

— A Jewish Barber

Context:

Mistaken for Adenoid Hynkel, the Jewish barber is brought before a massive rally and a radio microphone to deliver a victory speech after the invasion of a neighboring country. Instead of a hateful tirade, he delivers a heartfelt plea for peace and democracy.

Meaning:

This is the opening of the final, iconic speech. It immediately subverts the audience's expectations for a dictatorial address. It establishes the barber's (and Chaplin's) core message of humanism, empathy, and universal brotherhood, rejecting the very notion of conquest and domination that Hynkel represents.

Greed has poisoned men's souls, has barricaded the world with hate, has goose-stepped us into misery and bloodshed.

— A Jewish Barber

Context:

This is part of the barber's powerful monologue at the end of the film, where he diagnoses the world's ills before offering a message of hope and a call to action.

Meaning:

This line from the final speech identifies greed and hatred as the root causes of the world's suffering and conflict. It's a powerful indictment of the ideologies that fuel fascism and war, suggesting these are not natural human states but rather poisons that have corrupted humanity.

You, the people, have the power — the power to create machines. The power to create happiness! You, the people, have the power to make this life free and beautiful, to make this life a wonderful adventure.

— A Jewish Barber

Context:

Towards the end of his impassioned speech, the barber addresses the soldiers and the world, urging them to reclaim their power and fight for a better future.

Meaning:

This is the climax of the speech, a direct empowerment of the common person. Chaplin shifts the focus from leaders and regimes to the collective power of humanity. It's a deeply democratic and optimistic message, arguing that the tools for progress and happiness are in the hands of the people, not dictators.

Look up, Hannah. The soul of man has been given wings and at last he is beginning to fly. He is flying into the rainbow — into the light of hope.

— A Jewish Barber

Context:

The barber concludes his speech with a message of hope and a vision of a brighter future. The scene cuts to Hannah in a field, listening to the broadcast, her face filled with renewed hope as she looks towards the sky.

Meaning:

These are the final words of the film, delivered as part of the barber's radio address. It is a direct message of hope to Hannah and, by extension, to all victims of oppression. It encapsulates the film's ultimate belief in the triumph of the human spirit over darkness and despair.

Philosophical Questions

What is the nature of power and how does it corrupt?

The film explores how the pursuit of absolute power dehumanizes individuals. Hynkel is not just evil; he is depicted as a ridiculous, insecure man-child whose cruelty stems from his own inadequacies. His obsession with control is shown to be a pathetic and ultimately futile endeavor, symbolized by his dance with the globe balloon that ultimately bursts. The film posits that true power lies not in domination but in the unity and will of the people.

Can humor be an effective weapon against tyranny?

"The Great Dictator" is built on the premise that ridicule can be a powerful form of resistance. By satirizing Hitler's mannerisms, his ideology, and the pageantry of his regime, Chaplin strips away his mystique and exposes the absurdity at the heart of his power. The film argues that laughter can be an act of defiance, a way to reclaim one's humanity and reject the fear that dictatorships rely upon to maintain control.

What is the responsibility of the artist in times of political crisis?

By making the film against the advice of many and in a climate of political caution, Chaplin makes a definitive statement about the artist's role in society. The film, and especially its final speech, argues that art cannot be neutral in the face of injustice. Chaplin uses his global platform not just to entertain but to advocate for a specific moral and political stance, suggesting that artists have a responsibility to use their voice to speak out against oppression and fight for a more humane world.

Alternative Interpretations

While the film's primary message is a straightforward condemnation of fascism, some critical interpretations have explored more nuanced aspects. One perspective focuses on the psychological doubling of the barber and the dictator. The fact that Chaplin plays both roles has been interpreted not just as a narrative convenience, but as a suggestion of a deeper connection—a commentary on the potential for both good (the barber) and evil (Hynkel) within a single persona, or even humanity itself. Charles Chaplin Jr. noted his father's fascination and horror with Hitler, and the sense that their roles as comic and madman "could have been the other way around," lending credence to this reading.

The controversial final speech has also been subject to varied interpretations. While most see it as a sincere humanist plea from Chaplin himself, some critics at the time and since have viewed it as an artistic misstep that breaks the narrative illusion of the film. They argue that by dropping the character of the barber and speaking directly as Chaplin, he sacrifices storytelling for propaganda. Conversely, others see this breaking of the fourth wall as a necessary and powerful rhetorical device, arguing that the urgency of the historical moment demanded such a direct address, transforming the film from mere entertainment into a vital political act.

Cultural Impact

"The Great Dictator" stands as a landmark of political satire and a testament to the power of cinema as a tool for social commentary. Released in 1940, it was a courageous and highly controversial film, as it directly attacked Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime while the United States was still officially neutral in World War II. Many in Hollywood and Washington feared the film would be dangerously provocative. Despite this, the film was a great commercial success and was popular with audiences in the U.S. and the U.K.

Its influence on cinema is profound. It demonstrated that comedy could be used to address the most serious and terrifying of subjects, blending slapstick humor with a powerful humanist message. The film's direct-to-camera final speech was a radical departure from narrative convention and remains one of the most famous and debated monologues in film history. Critics at the time were divided, with some finding the speech preachy or out of place, but its estimation has grown over time, and it is now widely seen as a powerful and prescient plea for peace.

The film had a significant impact on Chaplin's own life and career, solidifying his public image as a political activist and drawing the ire of isolationists and later, anti-communist crusaders. It remains a historically significant work, praised for its courage and its masterful integration of comedy and politics. In 1997, it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

Audience Reception

Upon its release, "The Great Dictator" was a significant box office success, becoming Chaplin's most commercially successful film. It was very popular with the American public and also drew large audiences in the United Kingdom. Critics were largely positive, with many praising it as a masterful and important work of satire. The New York Times, for example, called it "a truly superb accomplishment by a truly great artist."

However, the film was not without its critics. The final speech was a point of contention, with some reviewers finding it to be an overly sentimental and preachy departure from the film's comedic tone, believing Chaplin should have let the satire speak for itself. There was also political controversy, with isolationists and Nazi sympathizers condemning the film for its interventionist message. Over time, critical appreciation for the film, including the final speech, has grown immensely, and it is now widely regarded as a courageous and historically vital masterpiece.

Interesting Facts

- This was Charlie Chaplin's first true sound film.

- Chaplin later stated in his autobiography that if he had known the true extent of the horrors of the Nazi concentration camps, he could not have made the film.

- The film was released when the United States was still formally at peace with Nazi Germany, making its direct criticism of Hitler and fascism a bold and controversial act.

- Adolf Hitler reportedly saw the film, with one account suggesting he viewed it twice, alone.

- Chaplin got the idea for the film after a friend, Alexander Korda, noted his physical resemblance to Hitler.

- Chaplin and Hitler were born within four days of each other in April 1889.

- The film was nominated for five Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actor for Chaplin, and Best Supporting Actor for Jack Oakie, but won none.

- The names of the characters and countries are satirical puns: Adenoid Hynkel for Adolf Hitler, Benzino Napaloni for Benito Mussolini, Garbitsch (garbage) for Goebbels, and Herring for Göring. The country Tomainia is a play on "ptomaine" poisoning.

- Chaplin funded the $2 million production almost entirely himself because Hollywood studios were wary of the political subject matter.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!