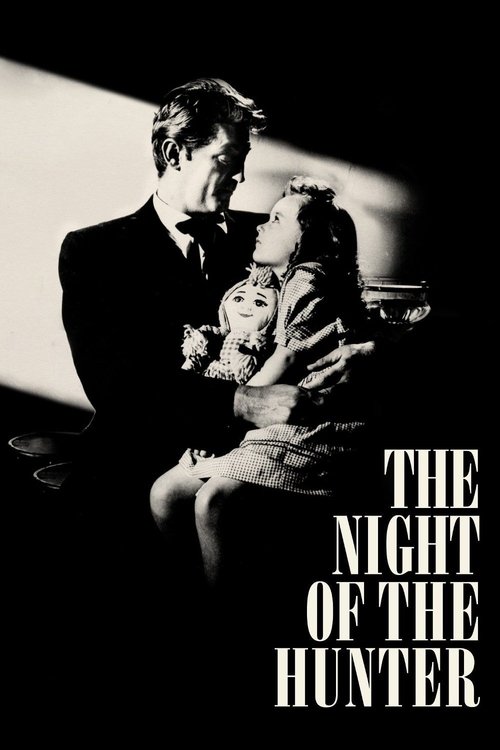

The Night of the Hunter

"It’s a hard world for little things."

Overview

Set during the Great Depression in West Virginia, "The Night of the Hunter" tells the story of two young children, John and Pearl Harper. Their father, Ben, is executed for robbing a bank and killing two men, but not before he hides the $10,000 bounty and makes his children swear to keep its location a secret. While in prison, he shares a cell with the charismatic but sinister 'Preacher' Harry Powell, a serial killer who preys on widows.

Upon his release, the predatory Powell, with the words "LOVE" and "HATE" tattooed on his knuckles, makes his way to the Harper family's small town. He effortlessly charms the locals and seduces the children's vulnerable mother, Willa, marrying her with the sole intention of finding the hidden money. While Pearl is susceptible to his charms, young John remains deeply suspicious and protective of their secret. Powell's patient facade soon crumbles, revealing the violent wolf beneath the sheep's clothing, forcing the children to flee for their lives down the Ohio River, with the relentless hunter in pursuit.

Core Meaning

At its core, "The Night of the Hunter" is an allegorical fable about the primordial struggle between good and evil, and the perilous journey of innocence through a corrupt adult world. Director Charles Laughton crafts what he called "a nightmarish sort of Mother Goose tale," exploring the potent dangers of religious hypocrisy and blind faith. The film posits that true faith and goodness, embodied by the resilient matriarch Rachel Cooper, are not found in loud, performative piety but in quiet strength, endurance, and protective love. It serves as a powerful cautionary tale, suggesting that evil often wears a deceptively holy mask and that the resilience of children is a formidable force against the darkness.

Thematic DNA

Good vs. Evil

The film presents a stark, almost Biblical, conflict between absolute good and absolute evil. Harry Powell is the embodiment of pure malevolence, a "ravening wolf" in sheep's clothing, while Rachel Cooper is his antithesis, a protective, saintly figure who is a "strong tree with branches for many birds." This duality is most famously symbolized by Powell's "LOVE" and "HATE" knuckle tattoos, which he presents as a story of an eternal struggle. The entire narrative is a flight from the forces of hate toward the sanctuary of love, culminating in a direct confrontation between these two archetypal forces.

Religious Hypocrisy

"The Night of the Hunter" is a scathing critique of the weaponization of religion. Powell uses the language of the pulpit to manipulate, seduce, and terrorize. He fools an entire town of seemingly devout people who are taken in by his performance of piety. In contrast, Rachel Cooper embodies true Christian charity and strength without ostentatious preaching. The film draws a clear distinction between performative, self-serving faith (Powell) and genuine, protective faith (Rachel), warning against the dangers of false prophets.

The Corruption of Innocence

The story is largely told from the perspective of the children, John and Pearl, making their loss of innocence a central theme. They are thrust into a terrifying world where adult authority figures either fail them—like their naive mother Willa and the drunken Uncle Birdie—or actively hunt them. Their journey down the river is both a literal and symbolic flight from the corrupting influence of Powell's evil, a desperate attempt to preserve their lives and the secret their father burdened them with. Their ordeal forces them to confront the darkest aspects of human nature far too soon.

The Great Depression and Greed

The film is set against the backdrop of the Great Depression, an era of widespread poverty and desperation that motivates the actions of key characters. Ben Harper's initial crime is an attempt to provide for his children. Powell's evil is driven by a relentless greed for the $10,000, which he sees as his divine right. The gullibility of the townspeople can be seen as a symptom of their desperation, making them eager to believe in a charismatic figure who promises salvation and order.

Character Analysis

Reverend Harry Powell

Robert Mitchum

Motivation

Powell is motivated by a combination of avarice and a deep-seated, misogynistic hatred disguised as religious righteousness. He tells God he hates "perfume-smelling things, lacy things," justifying his murders of women as a holy crusade. His primary, tangible goal is to acquire the $10,000 stolen by Ben Harper.

Character Arc

Harry Powell is a static character, a force of pure, unchanging evil. He does not grow or learn; he simply is. His journey is a relentless, single-minded pursuit of money, using a facade of religious piety. His 'arc' is one of exposure, where his mask is finally stripped away by Rachel Cooper's resilience and the town's eventual realization of his true nature, leading to his capture.

Rachel Cooper

Lillian Gish

Motivation

Motivated by a profound, practical Christian faith and a maternal instinct to protect "little things," Rachel has dedicated her life to caring for lost and abandoned children. Having lost her own son, she channels her love and resilience into safeguarding the vulnerable, becoming the steadfast guardian the Harper children desperately need.

Character Arc

Rachel Cooper is the film's moral anchor and a symbol of enduring goodness. Her character is also largely static, but in a positive sense; she is an unwavering protector from the moment she appears. Her arc is about facing the ultimate test of her faith and strength when Powell arrives. She proves to be the formidable matriarch, a "strong tree with branches for many birds," who confronts evil head-on and wins.

John Harper

Billy Chapin

Motivation

John's sole motivation is to honor the promise he made to his father: to protect Pearl and never reveal the location of the money. This oath drives his every action, from his mistrust of Powell to his desperate flight down the river. His love for his sister is the source of his incredible endurance.

Character Arc

John's arc is the emotional core of the film. He is forced to mature prematurely, taking on the adult burden of protecting his younger sister and their father's dangerous secret. His journey is from fearful suspicion to outright defiance. He initially trusts no one, but under Rachel Cooper's care, he slowly learns to let his guard down and accept protection, finally able to be a child again after Powell is captured.

Willa Harper

Shelley Winters

Motivation

Willa is motivated by loneliness, a desire for a husband, and a deep-seated sense of guilt and shame which Powell exploits. She craves redemption and believes Powell is a man of God who can provide it, leading her to ignore John's warnings and her own instincts.

Character Arc

Willa's arc is a tragic one of spiritual and physical demise. Initially a lonely, vulnerable widow, she falls for Powell's deceptive piety, desperate for love and guidance. She transitions into a state of religious delusion, believing their sexless marriage is a path to her salvation. Her tragic awakening to Powell's true nature comes just moments before he murders her. Her final, haunting underwater scene symbolizes her ultimate victimization.

Symbols & Motifs

LOVE / HATE Tattoos

The tattoos on Powell's knuckles are the film's most iconic symbol, representing the duality of human nature and the central conflict of good versus evil. They are a physical manifestation of the internal war Powell claims is fought within all of humanity, a sermon he uses to manipulate and intimidate. Ironically, while he preaches this balance, he is almost entirely consumed by hate.

Powell performs a chilling "sermon" with his hands, making his fingers wrestle to illustrate the story of love and hate. The tattoos are a constant visual reminder of his duplicitous and dangerous nature, reducing a complex moral struggle to a crude and violent parable.

The River

The Ohio River symbolizes a journey from danger to sanctuary, a path of escape and purification for the children. It is a mythic, dreamlike space, populated by the creatures of the natural world, representing a temporary haven from the horrors of the adult world. It has been compared to the journey of Moses in the bulrushes.

After escaping Powell, John and Pearl drift down the river in a small skiff. The journey is depicted in a lyrical, almost surreal sequence, with shots of animals on the shore watching them pass. This dreamlike escape contrasts sharply with the stark, expressionistic horror of the scenes with Powell.

Spiders and Webs

The spider web is a powerful symbol of the trap Powell has laid for the children and their mother. Powell is the predatory spider, and his victims are the flies caught in his web of deceit and religious rhetoric.

During their river journey, the children's boat floats under a giant, shimmering spider's web, visually representing the danger they are still in. Earlier, a stylized spider and web are seen as the children flee Powell, reinforcing his predatory nature.

Pearl's Doll

The doll, where the stolen money is hidden, symbolizes corrupted innocence. It is an object of childhood comfort and love, but it has become the container for the source of all their danger and trauma—the adult world's obsession with money. Pearl's fierce attachment to it puts them in constant peril.

Ben Harper stuffs the $10,000 into Pearl's doll before his arrest. Throughout the film, Powell relentlessly tries to get Pearl to reveal the money's location, manipulating her through the doll. The doll is the MacGuffin of the story, the object driving the entire terrifying hunt.

Animals (Owl, Rabbit, Fox, Sheep)

The animals observed during the river journey serve as a fable of the natural world, reflecting the children's plight. They represent the concepts of predator and prey, hunter and hunted. An owl snatching a rabbit from the riverbank mirrors Powell's predatory nature and the vulnerability of the children. The sheep at Rachel's farm represent the flock of lost children she protects.

In a beautifully shot montage, the camera cuts between the children sleeping in the boat and various nocturnal animals. This sequence universalizes their struggle, placing it within the larger, amoral context of the natural world where survival is a constant battle.

Memorable Quotes

Beware of false prophets, which come to you in sheep's clothing, but inwardly they are ravening wolves.

— Rachel Cooper

Context:

The film opens with Lillian Gish's face floating among stars, speaking directly to the audience (and a group of children's faces) as if telling a Sunday school lesson. This frames the entire narrative as a cautionary tale.

Meaning:

This opening line, a direct quote from Matthew 7:15, establishes the film's central theme and foreshadows the arrival of Harry Powell. It sets the stage for a story that is not just a thriller, but a moral allegory about discerning true goodness from deceptive evil.

The story of life is a story of conflict... the story of love and hate. The right hand, friends, the hand of love. The left hand, the hand of hate.

— Reverend Harry Powell

Context:

Powell often performs this story, making his hands wrestle one another in a theatrical display. It is his main tool of seduction, used to win the trust of the townspeople and Willa, masking his predatory intentions with philosophical and religious gravitas.

Meaning:

This quote is Powell's signature sermon and the primary explanation for his famous knuckle tattoos. It is a chillingly simplistic and manipulative parable he uses to enthrall and disarm his listeners, presenting himself as a man who understands the deep struggles of the human soul while being a monstrous embodiment of hate himself.

It's a hard world for little things.

— Rachel Cooper

Context:

Rachel says this as she takes in John and Pearl, recognizing the immense hardship they have endured. It's a moment of quiet understanding and compassion that contrasts sharply with the loud, empty rhetoric of Powell.

Meaning:

This simple, poignant line encapsulates Rachel's worldview and the film's deep empathy for the plight of children. It acknowledges the cruelty and danger of the world while reinforcing her role as a fierce protector of the vulnerable. It's a statement of fact, not of defeat.

Children are man at his strongest. They abide. And they endure.

— Rachel Cooper

Context:

Spoken at the end of the film, as Rachel prepares for Christmas with her flock of children, including John and Pearl. It is a final, hopeful meditation on the survival of innocence in the face of evil.

Meaning:

This is the film's ultimate thesis statement on childhood resilience. Rachel recognizes that children possess a unique and powerful capacity for endurance that adults often lose. It reframes their vulnerability as a form of profound strength. The Coen Brothers later echoed this line in The Big Lebowski with the phrase "The Dude abides."

Philosophical Questions

What is the true nature of faith and goodness?

The film contrasts two forms of Christianity. Harry Powell's is performative, loud, and used as a weapon for personal gain and to justify hatred. Rachel Cooper's is quiet, practical, and expressed through selfless action and protection of the vulnerable. The film asks the viewer to consider whether faith is defined by public declarations and scripture-quoting or by private acts of compassion and endurance. It posits that true goodness is resilient and protective, not judgmental and punitive.

Can innocence survive in a fundamentally corrupt world?

John and Pearl are vessels of innocence who are forced on a terrifying journey through the heart of adult corruption, greed, and violence. The adults in their lives repeatedly fail to protect them until they find Rachel. The film explores the immense resilience of children, suggesting that while their innocence can be scarred and tested, it has a powerful will to "abide and endure." The ending offers a hopeful, if not simplistic, answer: innocence can be preserved, but only through the intervention of genuine, unwavering goodness.

Where is the line between righteous judgment and hateful hypocrisy?

Through the character of Harry Powell, the film scrutinizes the human tendency to cloak personal hatred and prejudice in the language of religious morality. Powell genuinely seems to believe his misogyny is a holy crusade. The townspeople who embrace him are quick to judge Willa and even quicker to form a lynch mob against Powell once he's exposed. The film raises the question of whether any human is truly qualified to pass righteous judgment, suggesting that a focus on condemnation ('HATE') inevitably leads to violence, while true strength lies in compassion ('LOVE').

Alternative Interpretations

While the central theme of good versus evil is clear, "The Night of the Hunter" invites several interpretive lenses:

- A Dark Fairy Tale: Many critics interpret the film not as a realistic thriller, but as a live-action fairy tale. Harry Powell is the archetypal 'Big Bad Wolf' stalking the 'little pigs' (the children), who must flee to a safe house. Rachel Cooper serves as the protective 'fairy godmother' figure. The film's stylized, dream-like visuals and clear moral archetypes support this reading.

- Southern Gothic Horror: The film is a prime example of the Southern Gothic genre, using its Depression-era West Virginia setting to explore themes of religious fanaticism, decay, and grotesque characters hidden beneath a veneer of piety. The oppressive atmosphere and focus on flawed, desperate characters are hallmarks of this style.

- A Freudian Psychological Thriller: Some analysis has viewed the film through a Freudian lens, focusing on Powell's repressed sexuality and psychopathic misogyny. His obsession with his knife and his violent reactions to female sexuality suggest deep-seated psychological pathologies. The conflict between John and Powell can also be seen as an Oedipal struggle over the mother, Willa.

- A Critique of American Populism: The ease with which Powell manipulates the entire town can be read as a political allegory. His charismatic, simplistic rhetoric and appeals to religious morality sway the populace, who are quick to follow him and later, just as quick to form a lynch mob. This can be seen as a critique of the dangers of mob mentality and charismatic, but hollow, leadership.

Cultural Impact

Upon its release in 1955, "The Night of the Hunter" was a critical and commercial disaster. Audiences and critics were perplexed by its strange blend of horror, fairy tale, and religious allegory, and its stark, expressionistic style was out of step with the cinematic trends of the era. The failure deeply affected Charles Laughton, who never directed another film.

However, in the decades that followed, the film underwent a significant re-evaluation, beginning in the 1970s with the rise of auteur theory and expanded film criticism. It is now widely regarded as a masterpiece of American cinema and one of the greatest films ever made. Its influence is profound and far-reaching. Directors like Martin Scorsese, the Coen Brothers, Spike Lee, David Lynch, and Guillermo del Toro have all cited the film as a major influence on their work.

The film's daring visual language, which drew heavily from German Expressionism and silent film techniques, created a unique, nightmarish aesthetic that has been emulated countless times. Robert Mitchum's portrayal of Reverend Harry Powell is considered one of the most terrifying and iconic villains in film history. The "LOVE" and "HATE" tattoos have become an indelible part of pop culture, famously referenced in films like "Do the Right Thing." In 1992, "The Night of the Hunter" was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

Audience Reception

Upon its 1955 release, audience reception was largely negative, mirroring the baffled critical response. The film was a box office failure, a result that profoundly discouraged director Charles Laughton. Audiences of the time were reportedly confused and put off by its unique blend of genres—it wasn't a straightforward thriller, horror, or drama—and its stark, artistic visual style was unlike mainstream Hollywood productions.

In the modern era, however, audience reception has completely reversed. The film is now considered a beloved masterpiece by cinephiles and holds very high ratings on sites like IMDb and Rotten Tomatoes. Contemporary audiences praise Robert Mitchum's terrifying performance as one of cinema's greatest villains, the film's haunting and beautiful cinematography, and its suspenseful, dread-filled atmosphere. While some modern viewers find the acting of the children or the simplicity of the good-versus-evil narrative a bit dated, the overwhelming consensus is that it is a powerful, unique, and unforgettable film that was decades ahead of its time.

Interesting Facts

- This was the first and only film directed by acclaimed actor Charles Laughton. The film's initial critical and commercial failure was so personally devastating that he never directed again.

- Robert Mitchum was very eager for the role of Harry Powell. When Laughton described the character as "a diabolical shit," Mitchum reportedly replied, "Present!"

- The iconic underwater shot of the murdered Willa Harper, her hair flowing with the seaweed, was filmed in a studio tank with a mannequin. However, Shelley Winters also learned to hold her breath for an extended period for other takes.

- The film's visual style was heavily influenced by silent films, particularly the works of D.W. Griffith. Laughton's casting of silent-era superstar Lillian Gish was a deliberate tribute to this influence.

- Cinematographer Stanley Cortez, who also shot Orson Welles' "The Magnificent Ambersons," was one of only two directors Mitchum said truly understood light, the other being Welles.

- The script is credited to famed writer James Agee, but Laughton performed significant, uncredited rewrites on Agee's lengthy first draft.

- The surreal shot of Powell on the horizon was achieved using forced perspective, with a little person riding a pony to make the figure appear farther away and more unnatural.

- The story is based on the real-life case of Harry Powers, a serial killer who was hanged in 1932 in Clarksburg, West Virginia, for murdering two widows and three children.

- Gary Cooper was originally offered the role of Harry Powell but turned it down, fearing it would be detrimental to his heroic image.

Easter Eggs

In Spike Lee's 1989 film "Do the Right Thing," the character Radio Raheem wears large, four-fingered rings that say "LOVE" and "HATE."

This is a direct and famous homage to Harry Powell's knuckle tattoos. Raheem delivers a monologue that is an almost verbatim recitation of Powell's speech about the struggle between the two forces, updating its context for a modern story about racial tension.

The line "They abide and they endure" spoken by Rachel Cooper at the end of the film.

The Coen Brothers, who were heavily influenced by the film, paid homage to this line in "The Big Lebowski" (1998). The narrator, Sam Elliott, concludes the film by saying of the protagonist, "The Dude abides," echoing the theme of quiet, persistent endurance.

The menacing, stalking antagonist pursuing children.

Robert Mitchum's portrayal of Harry Powell directly inspired Robert De Niro's performance as Max Cady in the 1991 remake of "Cape Fear." Both characters are terrifying, Bible-quoting predators with tattoos who relentlessly stalk a family.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!