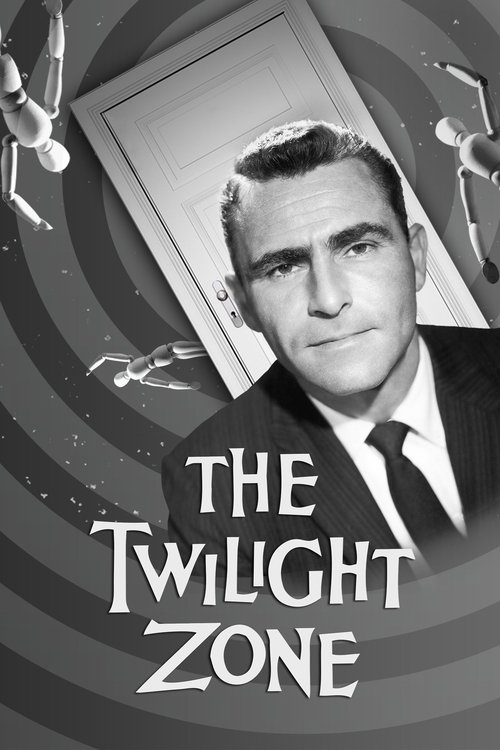

The Twilight Zone

"You are about to enter another dimension."

Overview

Created and hosted by the iconic Rod Serling, The Twilight Zone is an anthology series that transports viewers to a dimension of imagination. Each standalone episode tells a distinct story featuring different characters who find themselves in inexplicable, often supernatural, situations. There is no overarching plot connecting the episodes; instead, the series is unified by its tone and its exploration of the human condition under bizarre and stressful circumstances. Across its five seasons, the show delves into genres ranging from science fiction and fantasy to horror and psychological thrillers, consistently culminating in a shocking twist ending and a poignant moral lesson delivered by Serling himself.

The stories scrutinize human nature, questioning societal norms, prejudice, war, and technology through allegorical tales. Whether it's a man finding himself completely alone in the world, neighbors turning on each other out of paranoia, or a woman desperate to alter her appearance, the series uses fantastical scenarios to comment on real-world anxieties of the Cold War era, such as nuclear holocaust, McCarthyism, and social conformity. Serling used the genres of science fiction and fantasy as a vehicle to explore controversial social themes that would have otherwise been censored by television networks and sponsors at the time.

Core Meaning

The core meaning of The Twilight Zone is a profound and enduring exploration of the human condition, stripped down to its most essential fears, desires, and moral failings. Creator Rod Serling used the guise of science fiction and fantasy to craft modern-day parables, holding up a mirror to society's anxieties about conformity, nuclear annihilation, prejudice, and the dehumanizing potential of technology. The series posits that the greatest monsters are not aliens from another planet, but the darkness that resides within ordinary people—our paranoia, hatred, and ignorance. Ultimately, the 'Twilight Zone' is not just another dimension, but a space within the human mind itself, where reason gives way to fear and morality is put to the ultimate test. It serves as a timeless warning that the capacity for both heaven and hell lies within ourselves and our choices.

Thematic DNA

Humanity's Fear of the Unknown and Each Other

Throughout the series, the most terrifying threats are often not external but internal, stemming from paranoia and suspicion. Episodes like "The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street" masterfully illustrate how quickly societal bonds can dissolve when fear takes hold, turning neighbors into a hysterical mob searching for a scapegoat. This theme reflects the Cold War anxieties of the era, including McCarthyism and the fear of unseen enemies. The series repeatedly argues that the true monsters are prejudice, suspicion, and irrational fear, which are more destructive than any alien invasion.

The Nature of Reality and Identity

Many episodes blur the lines between reality, dream, and delusion, forcing characters and viewers to question their perceptions. Stories often feature protagonists who find themselves in surreal, alternate realities or grapple with a lost sense of self, as seen in the pilot episode "Where Is Everybody?". This theme delves into existential questions about what constitutes identity and whether our reality is as stable as we believe. It explores the psychological fragility of the human mind when faced with isolation and the inexplicable.

The Irony of Fate and Poetic Justice

A hallmark of the series is its use of ironic twist endings that deliver a form of cosmic justice. Characters who are greedy, selfish, or cruel often receive a fitting, albeit supernatural, comeuppance. Conversely, characters who are downtrodden often find escape, though sometimes in a tragic or ironic way. The classic episode "Time Enough at Last" provides the ultimate example of tragic irony, where a book lover survives the apocalypse with all the time in the world to read, only for his glasses to break. These endings serve as moral fables, warning against human folly and vice.

Nostalgia, Time, and Mortality

The series frequently explores the human desire to escape the present and return to an idealized past, as seen in episodes like "Walking Distance." This nostalgic longing is often portrayed as a bittersweet and ultimately impossible dream. The theme also encompasses the fear of death and the desperate search for immortality or a second chance. Stories grapple with aging, loss, and the relentless passage of time, questioning whether humanity can ever truly escape its mortal coil.

Character Analysis

Rod Serling

Rod Serling

Motivation

Serling's motivation, both as a writer and host, was to explore complex social and moral issues that were censored in mainstream television dramas. By cloaking his commentary in science fiction and fantasy, he could critique prejudice, war, McCarthyism, and other controversial topics. His goal was to make the audience think about their own world by presenting them with cautionary tales from another dimension.

Character Arc

As the creator, primary writer, and host, Rod Serling is the constant presence and guiding force of the series. He does not have a character arc in the traditional sense, as he exists outside the narrative of each episode. However, his on-screen presence evolved. In the first season, he was primarily a voice-over narrator, but from the second season onward, he began appearing on-screen to introduce and conclude each story, becoming the face of the show. His role is that of a modern-day Greek chorus, providing context, moral commentary, and a bridge between the viewer's world and the strange dimension they are about to enter.

The Everyman

Various (e.g., Burgess Meredith, William Shatner)

Motivation

The motivation of the Everyman protagonist is almost always survival and a desperate desire to return to normalcy. They are not heroes seeking adventure but ordinary people trying to make sense of the inexplicable. Whether it's a man on an airplane seeing a creature on the wing or a bank teller who just wants to be left alone to read, their primary drive is to escape the terrifying predicament they've fallen into and restore order to their lives.

Character Arc

The Twilight Zone is an anthology, so its protagonists are different in each episode. However, a recurring archetype is the "Everyman"—an ordinary, relatable person suddenly thrust into an extraordinary situation. Their arc is compressed into a single episode, typically moving from a state of normalcy to confusion, terror, and finally, a profound, often horrifying, realization. Their journey is not one of long-term growth but of a sudden, paradigm-shifting experience that forever alters their understanding of reality. These characters are the audience's surrogate, reacting with disbelief and fear as their world unravels.

The Antagonist

Various

Motivation

The motivation of the antagonist varies. Sometimes, as with the Kanamits in "To Serve Man," it is a deceptive plan for conquest. Other times, as with the gremlin in "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet," it is simply a malevolent force of chaos. Frequently, however, the "antagonist" is a social force or an ironic twist of fate, motivated by nothing more than the cold mechanics of poetic justice, designed to teach a moral lesson to the characters and the audience.

Character Arc

The antagonists in The Twilight Zone are rarely straightforward villains. They can be aliens, robots, supernatural beings, or, most often, the darker aspects of humanity itself. The true antagonist is often an idea or a human failing: paranoia in "The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street," vanity in "Eye of the Beholder," or cruelty in "Living Doll." The arc of these antagonists is to reveal the protagonist's (and humanity's) weakness. They serve as catalysts that strip away the veneer of civilization and expose the raw, often ugly, truth beneath.

Symbols & Motifs

The Doorway/Window

Symbolizes the entrance into another dimension or a different state of consciousness. It represents the thin veil between the known and the unknown, the ordinary and the fantastical. The iconic opening sequence features a floating door, cementing this as the primary gateway into the titular zone.

This motif appears in various forms throughout the series. In the opening credits, it's a literal door floating in space. In episodes like "Little Girl Lost," a portal to another dimension opens in a child's bedroom wall. Windows often serve a similar function, such as the airplane window in "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet," through which a character sees a terrifying reality no one else can.

Masks

Masks represent the hidden, true nature of individuals and the superficiality of societal standards. They can either conceal a monstrous interior or be forced upon someone to hide a truth that society deems unacceptable.

In "The Masks," a wealthy patriarch forces his greedy heirs to wear masks that reflect their vile inner selves, which eventually become their actual faces. In "Eye of the Beholder," the protagonist's face is wrapped in bandages (a type of mask) for most of the episode, hiding her from a society where conventional beauty is considered grotesque.

Dolls and Mannequins

These figures symbolize the loss of humanity, control, and free will. They often represent a sinister or uncanny version of human life, blurring the line between the animate and the inanimate and tapping into deep-seated fears of being controlled or replaced.

In "Living Doll," the seemingly innocent Talky Tina doll becomes a malevolent entity that terrorizes a cruel stepfather. In "The After Hours," a woman discovers she is a mannequin who is only allowed to live among humans for a limited time before returning to her inanimate state.

The Broken Glasses

This powerful symbol from the episode "Time Enough at Last" represents the ultimate cosmic irony and the fragility of human happiness. It signifies that even when one's greatest desire is fulfilled, a simple accident or twist of fate can render it meaningless.

Used memorably in "Time Enough at Last," where bibliophile Henry Bemis is the sole survivor of a nuclear holocaust with access to all the books he could ever want. His moment of triumph is shattered when his essential reading glasses fall and break.

Memorable Quotes

You're traveling through another dimension, a dimension not only of sight and sound but of mind. A journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination. That's the signpost up ahead—your next stop, the Twilight Zone!

— Rod Serling (Narrator)

Context:

This quote, in slightly varied forms, served as the opening narration for most episodes from Season 2 through 5, accompanying the now-famous theme music and surreal title sequence.

Meaning:

This iconic opening narration, used from the second season onward, perfectly encapsulates the series' premise. It's not just a catchphrase; it's a mission statement, promising viewers a journey into the abstract and the psychological. It establishes that the stories will explore the inner landscapes of human consciousness as much as outer space or supernatural realms.

The tools of conquest do not necessarily come with bombs and explosions and fallout. There are weapons that are simply thoughts, attitudes, prejudices... to be found only in the minds of men.

— Rod Serling (Narrator)

Context:

This is from the closing narration of the Season 1 episode, "The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street." After residents of a suburban street descend into paranoid violence, suspecting each other of being invading aliens, it's revealed that aliens were indeed watching, but their plan was simply to let humans destroy themselves.

Meaning:

This quote delivers the powerful, central message of its episode: the greatest threat to humanity is humanity itself. It argues that internal flaws like prejudice and suspicion are more destructive weapons than any physical arsenal, capable of tearing society apart from within.

That's not fair. That's not fair at all! There was time now. There was all the time I needed! That's not fair!

— Henry Bemis

Context:

Spoken by actor Burgess Meredith in the Season 1 episode "Time Enough at Last." Bemis, a bookworm who survives a nuclear blast, is overjoyed to find himself surrounded by the ruins of a library with endless time to read, only to have his thick glasses slip off and shatter on the ground.

Meaning:

This quote is the heartbreaking cry of a man whose lifelong dream is realized and then instantly, cruelly snatched away. It embodies the series' theme of cosmic irony, highlighting the indifferent, often cruel, nature of fate in the Twilight Zone.

All the Dachaus must remain standing... They are a monument to a moment in time when some men decided to turn the Earth into a graveyard... And the moment we forget this... then we become the gravediggers.

— Rod Serling (Narrator)

Context:

From the closing narration of the Season 3 episode "Deaths-Head Revisited." In the episode, a former Nazi Captain revisits the Dachau concentration camp and is tormented by the ghosts of his victims, who put him on trial and sentence him to insanity.

Meaning:

This is one of Serling's most direct and powerful moral statements in the series, a plea against forgetting the horrors of the Holocaust. It argues that remembrance, however painful, is essential to prevent such atrocities from happening again.

Episode Highlights

The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street

When a mysterious power outage and a flashing light in the sky disrupt a quiet suburban neighborhood, the residents' fear and suspicion quickly escalate. They begin to accuse one another of being alien invaders in disguise, leading to a complete breakdown of social order, mob mentality, and violence.

This episode is a powerful allegory for the paranoia of the Cold War and McCarthy-era witch hunts. It masterfully demonstrates how easily fear can turn neighbors into enemies and is one of the clearest examples of Rod Serling using science fiction to deliver sharp social commentary. Its message about the dangers of prejudice and scapegoating remains profoundly relevant.

Time Enough at Last

A henpecked, book-loving bank teller named Henry Bemis finds solace only in reading. During his lunch break in the bank's vault, a nuclear bomb detonates, leaving him the sole survivor on Earth. He is initially devastated, but then discovers the ruins of the public library and rejoices that he finally has all the time in the world to read without interruption.

This episode is famous for its devastatingly ironic twist ending, which became a signature of the series. It's a poignant and tragic exploration of loneliness and the cruelty of fate, and it remains one of the most iconic and frequently cited episodes of the entire show.

Eye of the Beholder

A woman named Janet Tyler lies in a hospital bed, her face completely covered in bandages. She has undergone her final state-mandated procedure to correct her hideous disfigurement. The doctors and nurses, whose faces are kept in shadow, discuss the tragedy of her condition. The tension builds until her bandages are removed.

This episode is a brilliant critique of conformity and societal standards of beauty. The shocking reveal—that the doctors and nurses are what we would consider grotesquely disfigured, while Janet is beautiful by our standards—forces the audience to confront the arbitrary nature of beauty. It's a powerful statement on social pressure and the pain of being an outsider.

Nightmare at 20,000 Feet

A man recently recovered from a nervous breakdown, Bob Wilson (played by William Shatner), is flying home with his wife. During the flight, he looks out the window and sees a hideous gremlin on the wing of the plane, tampering with the engine. No one else sees it, and his frantic attempts to convince his wife and the crew lead them to believe he is having a relapse.

Perhaps the most famous and widely parodied episode, it is a masterclass in suspense and psychological horror. It perfectly captures the terror of being the only one who sees a threat, and the maddening helplessness of not being believed. The story preys on common fears of flying and loss of control, becoming a cultural touchstone.

To Serve Man

A highly advanced and seemingly benevolent alien race, the Kanamits, arrives on Earth, offering solutions to all of humanity's problems: famine, war, and energy shortages. They leave behind a book, which cryptographers work tirelessly to translate. The title is translated as "To Serve Man," reassuring humanity of their peaceful intentions.

This episode features one of the most chilling and memorable twist endings in television history. The final reveal—that "To Serve Man" is a cookbook—is a shocking punchline that turns a story of hope into one of absolute horror. It's a cautionary tale about trust, deception, and the idiom "if it seems too good to be true, it probably is."

It's a Good Life

The small town of Peaksville, Ohio lives in absolute terror of a six-year-old boy named Anthony Fremont. Anthony has god-like mental powers: he can read minds and can make anything he wishes happen. The slightest displeasure can cause him to wish people or things away into a cornfield from which there is no return. The adults around him live in a constant state of feigned happiness, always telling him everything he does is "real good."

This is one of the most genuinely terrifying episodes of the series, exploring the horror of absolute power in the hands of a capricious child. It's a chilling allegory for tyranny and the psychological effects of living under constant fear, where expressing a negative thought can lead to annihilation.

Philosophical Questions

What defines a person?

The series repeatedly probes the essence of personhood. In "The Lonely," a convicted man on an asteroid is given a female android, Alicia, for companionship. He initially rejects her as a machine but eventually falls in love, treating her as human. The episode raises questions about whether consciousness, emotion, and personhood are dependent on biological origins or can be ascribed to a sufficiently advanced machine. When Alicia is cruelly destroyed, revealing her mechanical nature, the man's grief is real, forcing the audience to ask if his perception of her as a person was enough to make it so. Other episodes like "I Sing the Body Electric" also explore the capacity for love and humanity in artificial beings.

Is humanity's progress leading to its salvation or destruction?

The Twilight Zone often displays a deep skepticism towards technology and the notion of inevitable progress. Far from being a savior, technology in the series is frequently a source of dehumanization, alienation, or destruction. In "The Obsolete Man," a dystopian state declares a librarian obsolete because books have been banned. In "To Serve Man," advanced alien technology is a Trojan horse for humanity's doom. The series consistently warns that scientific advancement without a corresponding growth in wisdom and empathy can lead to catastrophic consequences, questioning whether humanity's tools will ultimately outpace its morality.

What is the nature of good and evil?

The series functions as a collection of morality plays, examining the eternal struggle between good and evil. However, it rarely presents this as a simple binary. Evil is often mundane, born from fear, prejudice, and selfishness, as seen in "The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street." Goodness is often found in acts of quiet empathy or sacrifice. The show explores whether evil is an external force or an inherent part of human nature. Episodes like "The Howling Man" depict evil as a literal entity that can be captured and released, while others suggest that the greatest evils are those we create ourselves.

Alternative Interpretations

While most episodes of The Twilight Zone present a clear moral, the anthology format and often ambiguous endings have invited various interpretations. One major area of discussion is the nature of the 'Zone' itself. Is it a literal dimension, a state of mind, a manifestation of divine or cosmic justice, or simply a narrative framework for exploring human psychology? Some interpretations suggest the Zone is a purgatorial space where characters are forced to confront their moral failings. Episodes like "The Hunt" explicitly deal with the afterlife, while others like "A Stop at Willoughby" can be seen as psychological breaks from reality or as actual journeys through time and space.

Another perspective views the series not just as a critique of its time but as a deeply personal reflection of Rod Serling's own experiences and traumas, particularly his service in World War II. Episodes dealing with war, death, and psychological distress can be interpreted as Serling processing his own nightmares on screen. This reading adds a layer of autobiography to the fantastic stories, suggesting the 'Zone' was also a landscape for his own personal exploration of fear and morality.

Cultural Impact

The Twilight Zone fundamentally changed television, elevating science fiction from kitschy escapism to a sophisticated medium for social commentary and adult drama. Premiering in 1959, at the height of the Cold War, the series captured the anxieties of an era defined by McCarthyism, nuclear paranoia, and racial tension. Rod Serling masterfully used allegory to explore controversial themes of prejudice ("Eye of the Beholder"), mob mentality ("The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street"), and the horrors of war ("Deaths-Head Revisited"), bypassing network censors who would have rejected such direct critiques in a standard drama.

Critically acclaimed from its first season, the series won Serling multiple Emmy Awards for his writing and a prestigious Hugo Award. While never a massive ratings hit during its initial run, its influence grew immensely through syndication, where it became a cultural touchstone. The phrase "the twilight zone" entered the popular lexicon to describe any surreal or inexplicable experience. The show's anthology format and signature twist endings influenced countless subsequent TV series and films, including Black Mirror, The Outer Limits, and the work of filmmakers like M. Night Shyamalan. Its legacy is that of a show that proved television could be a powerful tool for philosophical inquiry, challenging audiences to look at their own world through a different, more imaginative lens.

Audience Reception

Upon its debut in 1959, The Twilight Zone was met with widespread critical acclaim, with critics immediately recognizing it as something special and thought-provoking, a departure from the standard television fare. Rod Serling was lauded for his intelligent and creative writing, earning Emmy awards for the first season. However, it was never a ratings juggernaut and struggled with viewership and sponsorship throughout its run, even facing cancellation more than once. The shift to an hour-long format for the fourth season was generally not well-received, and the show returned to its half-hour format for its final season.

Despite its modest initial ratings, the show was beloved by those who watched it. Its true success and cultural saturation came through reruns and syndication, where it found a massive and enduring audience. Generations of viewers discovered the show after its original run, solidifying its status as a timeless classic. Today, the original series is held in extremely high regard by both critics and audiences, frequently cited as one of the greatest television shows of all time. Its themes are considered just as relevant now as they were in the 1960s, a testament to Serling's profound understanding of human nature.

Interesting Facts

- Rod Serling wrote or co-wrote 92 of the 156 episodes.

- The iconic theme music from the second season onward was created by splicing together two stock music cues from a CBS library, written by French avant-garde composer Marius Constant.

- Serling created the show partly because he was frustrated with sponsors and networks censoring his socially-conscious scripts for other shows; he found that he could tackle controversial topics like racism and war through the allegorical lens of science fiction.

- The phrase 'Twilight Zone' was an existing U.S. Air Force term for the point when a plane is landing and the horizon is not visible, which Serling thought he had invented.

- Orson Welles was considered for the role of narrator but his salary demands were too high, leading Serling to take on the job himself.

- The series had difficulty finding sponsors for its fourth season and was nearly canceled. It was temporarily replaced, then brought back in an hour-long format for Season 4, before returning to its original 25-minute runtime for the final season.

- In a cost-saving measure for the final season, the show purchased and aired a French short film, "An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge," which went on to win an Oscar.

- The first pilot script Serling wrote for the series was titled "The Time Element," which CBS initially shelved. It was later produced as an episode of "Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse," and its popularity convinced the network to greenlight The Twilight Zone.

Easter Eggs

The filming location known as Courthouse Square on the Universal Studios backlot was used for the pilot episode, "Where Is Everybody?".

This iconic set is instantly recognizable to film fans as the same central location for the town of Hill Valley in the Back to the Future trilogy, creating an interesting visual link between two major science fiction franchises.

A recurring name, 'Cadwallader', appears in multiple episodes.

In the episode "Escape Clause," the devil is named Cadwallader. The name reappears for a different character in "The Man in the Bottle." This was an inside joke by Serling, who often used character names from his life and experiences in Binghamton, New York.

The episode "A World of His Own" features a unique breaking of the fourth wall.

In the final scene of the Season 1 finale, the episode's protagonist, a writer who can bring characters to life, is confronted by Rod Serling himself. The writer then uses his power to erase Serling from existence by throwing his tape description into the fireplace. It was a meta, humorous ending that directly acknowledged the show's creator within its own fictional world.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!