3-Iron

빈집

"In the quietness of empty houses, love finds a voice."

Overview

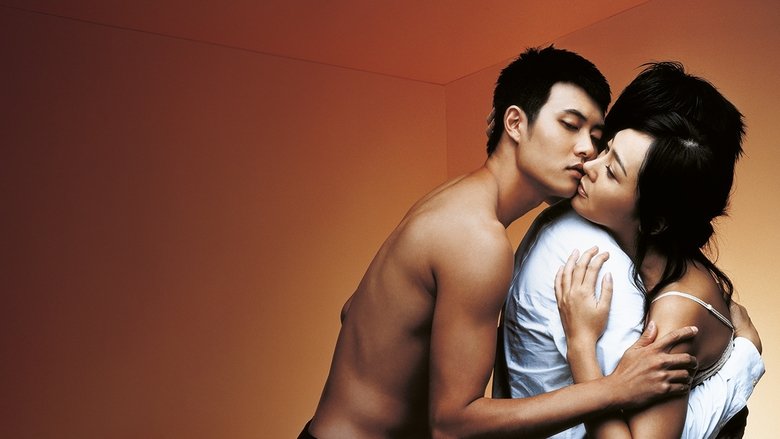

"3-Iron" follows Tae-suk, a young, silent transient who has a peculiar habit of breaking into empty houses. Rather than stealing, he temporarily lives in them, repaying his unwitting hosts by doing laundry and making small repairs. His solitary existence is disrupted when he enters a seemingly empty mansion and discovers Sun-hwa, a former model trapped in an abusive marriage.

Sun-hwa, bruised and silent herself, witnesses Tae-suk's gentle routines. After he defends her from her violent husband using a 3-iron golf club, she wordlessly decides to join him on his journey. Together, they move from one empty home to another, forming a deep, unspoken bond. Their phantom-like existence is a serene escape, but the outside world eventually intrudes, leading to their arrest after they are discovered in the home of a deceased man. Separated by the law, their connection is tested, pushing the narrative into a surreal and metaphysical exploration of love and presence.

Core Meaning

The core meaning of "3-Iron" revolves around the themes of invisibility, human connection beyond words, and the ambiguity between reality and fantasy. Director Kim Ki-duk explores the lives of marginalized individuals who exist like ghosts in the spaces of others, unseen and unheard. The film suggests that true connection transcends verbal communication and physical presence, becoming a spiritual or even ghostly bond. It poses existential questions about what constitutes reality, suggesting that our internal worlds and fantasies can be as real and meaningful as the physical world we inhabit. The final title card, "It's hard to tell whether the world we live in is a reality or a dream," encapsulates this central idea, inviting the audience to question the nature of the characters' existence and their ethereal reunion.

Thematic DNA

Silence and Non-Verbal Communication

The film's most striking feature is its near-total lack of dialogue between the two protagonists, Tae-suk and Sun-hwa. Their relationship is built entirely on shared experiences, gestures, and mutual understanding. Director Kim Ki-duk intentionally reduces dialogue to force the audience to observe the characters' behavior and expressions more closely, believing words are not always necessary for comprehension. This silence creates a profound intimacy, suggesting that the deepest connections are often unspoken and felt on a more intuitive, emotional level.

Invisibility and Marginalization

Tae-suk and Sun-hwa are societal ghosts. Tae-suk is a transient who leaves no trace, while Sun-hwa is invisible in her own home, silenced by abuse. Their practice of living in empty houses is a metaphor for their marginal status; they occupy the spaces of others without ever truly belonging. In prison, Tae-suk masters the art of literal invisibility, learning to hide in the blind spots of his guards. This skill becomes a metaphysical ability, allowing him to exist as an unseen presence, questioning the very nature of being seen and acknowledged.

Reality vs. Dream/Fantasy

The film deliberately blurs the line between what is real and what is imagined, particularly in its third act. After Tae-suk is released from prison, he seemingly returns to Sun-hwa as a ghostly, invisible entity that only she can perceive. This magical realist turn prompts multiple interpretations: Is Tae-suk physically present? Is he a ghost? Or is he a fantasy created by Sun-hwa to cope with her lonely, abusive reality? The film's final shot of them on a scale that reads zero reinforces this ambiguity, suggesting their love has transcended the physical world.

Freedom and Confinement

Both main characters seek escape from different forms of confinement. Sun-hwa is physically and emotionally trapped in her abusive marriage, making her home a prison. Tae-suk, though seemingly free in his nomadic lifestyle, is also confined by his detachment from society. Together, they find a temporary, liberating freedom in their shared transient life. Ultimately, Tae-suk achieves a higher form of freedom by transcending physical limitations, while Sun-hwa finds her own liberation by embracing his invisible presence within the confines of her home.

Character Analysis

Tae-suk

Jae Hee

Motivation

Initially, his motivation seems to be simple survival and a quiet, non-invasive way of living. He seeks temporary shelter and connection, which he finds by repairing objects. After meeting Sun-hwa, his motivation shifts to protecting her and preserving their unique, silent bond.

Character Arc

Tae-suk begins as a silent, solitary drifter who exists on the fringes of society, a ghost-like figure occupying the empty spaces of others. His connection with Sun-hwa introduces love and responsibility into his transient life, but also leads to conflict and his eventual imprisonment. In jail, he undergoes a profound transformation, moving from a physical wanderer to a metaphysical one. He masters the art of invisibility, transcending physical confinement to reunite with Sun-hwa on a spiritual plane. His arc is one of literal and figurative dematerialization.

Sun-hwa

Lee Seung-yun

Motivation

Her primary motivation is to escape the physical and emotional abuse of her husband and the suffocating emptiness of her life. She craves the genuine, gentle connection that Tae-suk offers, a relationship free from the violence and demands of her marriage.

Character Arc

Sun-hwa starts as a passive, abused wife, rendered invisible and voiceless in her own opulent home. Meeting Tae-suk awakens her desire for freedom and connection. By joining his silent, nomadic life, she breaks free from her physical confinement and rediscovers her agency. Though she is eventually returned to her husband, she is no longer a passive victim. She learns to harbor Tae-suk as an invisible presence, finding a way to coexist with her reality while nurturing a private, spiritual love that empowers her. Her final lines, "I love you," spoken to her husband but meant for Tae-suk, signify her complete inner transformation.

Min-gyu

Kwon Hyuk-ho

Motivation

His motivation is rooted in ownership and control. He sees his wife as a possession and reacts with anger and violence when she defies him or when his authority is challenged. He bribes police and acts out of jealousy and revenge, seeking to re-establish his dominance.

Character Arc

Min-gyu, Sun-hwa's husband, is a character who remains largely static. He is controlling, violent, and unable to understand his wife's unhappiness. He represents the oppressive forces of the conventional world that intrude upon the protagonists' idyllic existence. Even after Sun-hwa returns, he fails to perceive the profound change in her or the presence of his rival. He ends the film in a state of unknowing, sensing something is amiss but unable to comprehend the spiritual reality unfolding in his own home.

Symbols & Motifs

3-Iron Golf Club

The 3-iron symbolizes both violence and liberation. It is an instrument of aggression when Tae-suk uses it to attack Sun-hwa's abusive husband, but it's also a tool of defiance that facilitates her escape. The club itself is noted as one that is rarely used, mirroring the main characters who are alienated and overlooked by society. Tae-suk's practice of hitting tethered golf balls represents a contained, practiced form of rebellion. Later, in prison, his miming of a golf swing becomes a meditative act, transforming the symbol from a physical weapon to a tool for spiritual training and achieving invisibility.

The club is first seen with Sun-hwa's husband. Tae-suk uses it to hit golf balls at the husband, rescuing Sun-hwa. He continues to practice with it until a tragic accident occurs. In prison, he practices with an imaginary club, which is key to his transformation.

Empty Houses (Bin-jip)

The empty houses, the film's original Korean title ('Bin-jip'), represent the voids in the lives of both their owners and the main characters. For Tae-suk and Sun-hwa, these temporary homes are sanctuaries where they can build a silent, intimate world. They also function as windows into different lives, reflecting themes of social status, loneliness, and the superficiality of material possessions. The act of breaking in is less a violation and more an act of temporary symbiosis; Tae-suk repairs broken items, leaving the homes in better condition and connecting with the absent owners in a ghostly way.

The entire narrative is structured around the couple moving from one empty house to another. Each house has a distinct personality, from a traditional hanok to a modern, sterile apartment, reflecting the lives of the people they temporarily replace.

Photographs and Selfies

Tae-suk takes selfies with the possessions and portraits in the homes he visits. This act symbolizes his desire for connection, identity, and a place in the world. He inserts himself into the lives and families of others, trying to capture a sense of belonging that he lacks. The photographs are the only tangible records of his phantom existence, yet they are ultimately confiscated, erasing his physical footprint and pushing him further toward a purely spectral existence.

In several of the houses, Tae-suk carefully poses with family pictures and objects before taking a photo with his digital camera. The police later use these photos to track down the homeowners he visited.

The Bathroom Scale

The scale symbolizes weight, both physical and emotional, and the ultimate transcendence of it. Tae-suk fixes a broken scale in one of the first homes, an act of his gentle, restorative nature. The final scene, where he and Sun-hwa stand on the scale together and it registers "0", is one of the film's most powerful and enigmatic images. It suggests they have become weightless, existing on a different plane of reality, freed from the burdens of the physical world. Their love is not a tangible weight but a spiritual, ethereal force.

Early in the film, Tae-suk repairs a scale. The film concludes with Sun-hwa and the invisible Tae-suk standing on her scale at home. The display reads "0", as her husband looks on, confused.

Memorable Quotes

사랑해 (Saranghae)

— Sun-hwa

Context:

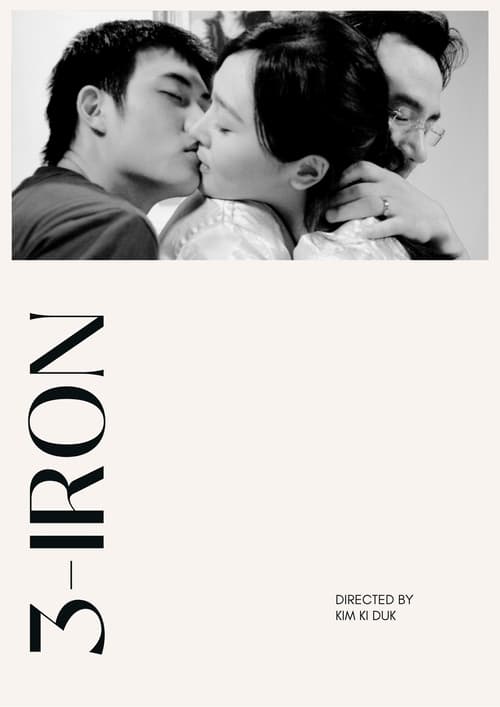

In the final scene, Sun-hwa is back in her house with her husband, Min-gyu. He embraces her, and she says "I love you." As she says this, she leans over his shoulder and kisses the invisible Tae-suk, who is standing behind him.

Meaning:

These are the only two words Sun-hwa speaks in the entire film, aside from a scream. Their placement at the very end is incredibly powerful. Spoken seemingly to her husband, they are truly directed at the invisible Tae-suk, whom she is kissing over her husband's shoulder. The quote signifies her ultimate liberation: she has found a way to express her true love and live in her own reality, completely unseen by her oppressor. It is a declaration of a love that transcends the physical and the visible.

It's hard to tell whether the world we live in is a reality or a dream.

— Narrative Text (Closing Title Card)

Context:

This text appears on screen just before the credits roll, after the final shot of Sun-hwa and the invisible Tae-suk standing together on the scale that reads "0".

Meaning:

This final statement encapsulates the film's central philosophical question. It directly invites the audience to question the nature of the events they have just witnessed. It suggests that the line between the objective world and subjective experience is blurred, and that love, memory, and fantasy can constitute a reality just as valid as the physical one. This quote solidifies the film's magical realist elements and leaves the ending open to profound and personal interpretation.

Philosophical Questions

What is the nature of reality and human connection?

The film fundamentally questions whether objective reality is the only valid one. Through its dreamlike logic and the final title card, "It's hard to tell whether the world we live in is a reality or a dream," the film suggests that our internal worlds—fantasies, dreams, and spiritual connections—can be equally, if not more, meaningful. The silent, profound bond between Tae-suk and Sun-hwa proposes that true human connection doesn't require words or even constant physical presence; it can be a shared state of being that transcends conventional communication and exists on a spiritual or telepathic level.

Can one be truly free while physically confined?

"3-Iron" explores different forms of freedom and confinement. Sun-hwa is a prisoner in her own luxurious home, while Tae-suk is physically free but socially invisible and detached. The climax of this theme occurs when Tae-suk is in jail. In the most extreme state of physical confinement, he achieves the ultimate freedom by mastering his perception and presence, learning to become invisible. The film argues that true freedom is an internal state of being, a form of spiritual transcendence that cannot be restricted by physical barriers.

Is it possible to exist without leaving a trace?

Tae-suk's lifestyle is an attempt to live without creating a permanent impact. He is a ghost who borrows spaces and leaves them slightly better than he found them. However, the film shows this is impossible. His actions inevitably have consequences: he falls in love, he commits an act of violence (however justified), and his golf ball causes a tragic accident. His attempt to remain a phantom fails, leading to his arrest and erasure from the physical world (his photos are confiscated). This suggests that human existence is inherently about connection and consequence, and to live is to affect the world and be affected by it, whether one wants to or not.

Alternative Interpretations

The film's ambiguous narrative, especially its ending, has generated numerous interpretations among critics and viewers.

- Tae-suk as Sun-hwa's Fantasy: One of the most popular interpretations is that Tae-suk is not a real person, but a figment of Sun-hwa's imagination. He is an idealized rescuer she creates to mentally escape her abusive marriage. His silent, gentle nature is the perfect antidote to her husband's loud, violent presence. In this reading, the entire journey is an internal one, and his "return" as a ghost is her final embrace of this fantasy, allowing her to find peace within her inescapable reality.

- Sun-hwa as Tae-suk's Fantasy: Director Kim Ki-duk himself suggested the reverse could also be true: that Sun-hwa is a fantasy created by the lonely Tae-suk. She represents the connection and purpose he lacks in his solitary life of drifting through empty homes. Their journey gives his existence meaning, and her presence is what he carries with him after his imprisonment.

- A Ghost Story: Another interpretation takes the film's events more literally, suggesting Tae-suk either dies in prison or achieves a state of spiritual enlightenment that allows him to become a ghost. His love for Sun-hwa is so strong that it transcends death or physical form, enabling him to return as an invisible protector and companion. The film then becomes a tale of love conquering all, even the boundary between life and death.

- A Metaphor for Class Struggle: Some analyses view the film through a socio-economic lens. Tae-suk, the homeless transient, represents the invisible and marginalized underclass. He temporarily inhabits the world of the affluent (symbolized by the empty houses and Sun-hwa's husband) but can never truly belong. His ultimate invisibility can be seen as a commentary on how society ignores the disenfranchised, who exist as ghosts within the system.

Cultural Impact

"3-Iron" arrived during a period of intense international interest in South Korean cinema, often referred to as the Korean New Wave. As a work by one of the movement's most distinctive and controversial auteurs, Kim Ki-duk, the film cemented his reputation for combining visceral themes with profound, often spiritual, and visually poetic storytelling. It stands in contrast to some of his more violent and overtly shocking works like "The Isle," offering a more meditative and tender, though still unsettling, narrative.

Critically, "3-Iron" was highly acclaimed, particularly in Europe, where it won the prestigious Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival. This reception highlighted the global appetite for films that challenge conventional narrative structures, especially through its radical use of silence. It influenced conversations around minimalist filmmaking and showed that a compelling romance could be built without dialogue, relying instead on pure cinematic language—action, expression, and cinematography.

Philosophically, the film taps into Buddhist and existential ideas about reality, illusion, and attachment. The concept of a person becoming a "ghost" in their own life, or transcending physical reality, resonated with audiences and critics exploring themes of modern alienation and spiritual longing. While not a mainstream blockbuster, its impact is felt in arthouse cinema circles, where it is often cited as a masterpiece of minimalism and a prime example of Kim Ki-duk's unique, often polarizing, genius.

Audience Reception

Audience reception for "3-Iron" is generally very positive, with many viewers hailing it as a beautiful, poetic, and deeply moving piece of cinema. Praised aspects frequently include the powerful storytelling achieved with minimal dialogue, which many found intensified the emotional connection between the protagonists. The chemistry between the leads, Jae Hee and Lee Seung-yun, is often highlighted as being remarkably palpable despite their silence. Viewers also appreciate the film's unique premise, its blend of gentle romance with moments of tension, and its beautiful, understated cinematography.

The main points of criticism or confusion tend to revolve around the film's third act and ambiguous ending. Some viewers find the shift into magical realism to be jarring or nonsensical, feeling it undermines the more grounded reality of the first two acts. The open-ended conclusion, while praised by many for its philosophical depth, leaves others feeling unsatisfied and wanting a more concrete explanation. Despite this, the overwhelming verdict from audiences who connect with its style is that "3-Iron" is a unique and unforgettable masterpiece.

Interesting Facts

- The film's Korean title is 'Bin-jip', which literally translates to 'Empty House'.

- Director Kim Ki-duk won the Silver Lion for Best Direction at the 61st Venice International Film Festival for this film.

- The idea for the film reportedly came to Kim Ki-duk when he found a flyer stuck in the keyhole of his own front door, making him wonder how a burglar might identify empty homes.

- The two main characters, Tae-suk and Sun-hwa, are almost entirely silent throughout the film. Tae-suk never speaks, and Sun-hwa only speaks two words at the very end.

- Kim Ki-duk has stated that he intentionally reduces dialogue in his films to make them more accessible to international audiences and to encourage viewers to focus on behavior and expression.

- The director has suggested multiple interpretations for the film, including one where Tae-suk is a fantasy created by Sun-hwa to escape her abuse, and another where Sun-hwa is a figment of Tae-suk's lonely imagination.

- Despite being one of South Korea's most internationally acclaimed directors, Kim Ki-duk's films, including '3-Iron', often received a more enthusiastic reception abroad than in his home country.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!