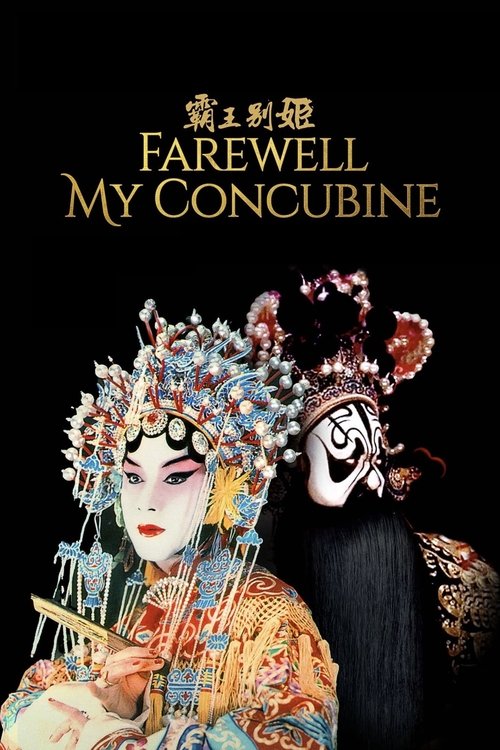

Farewell My Concubine

霸王别姬

"The passionate triangle of two lifelong friends and the woman who comes between them!"

Overview

Spanning over 50 years of tumultuous Chinese history from the 1920s to the 1970s, "Farewell My Concubine" chronicles the lives of two Peking Opera stars, Duan Xiaolou (Zhang Fengyi) and Cheng Dieyi (Leslie Cheung). Orphaned as a boy, Dieyi is apprenticed to an opera troupe where he forms a deep, lifelong bond with the more resilient Xiaolou. Dieyi is trained to play female roles (dan), while Xiaolou plays the heroic male roles (jing).

Their signature performance is the opera "Farewell My Concubine," where Xiaolou plays the King and Dieyi his devoted concubine, a role that Dieyi comes to embody in his real life, blurring the lines between performance and reality. His unrequited, obsessive love for Xiaolou forms the emotional core of the film. Their bond is irrevocably fractured when Xiaolou marries Juxian (Gong Li), a strong-willed courtesan, creating a volatile and tragic love triangle.

Against the backdrop of the Japanese invasion, the Communist takeover, and the brutal Cultural Revolution, the trio's personal dramas unfold. Their loyalties are tested, their art is threatened, and their lives are shattered by the relentless march of political change, leading to devastating betrayals and a tragic climax that mirrors the opera they are famous for.

Core Meaning

The core meaning of "Farewell My Concubine" is an exploration of the devastating impact of historical and political upheaval on individual lives, art, and identity. Director Chen Kaige uses the intimate story of the three protagonists to paint a grand historical epic, suggesting that personal identity and relationships are fragile constructs, easily shattered by the forces of ideology and societal change. The film questions the nature of identity itself—whether it is innate or performed—by blurring the lines between the stage and reality. Ultimately, it is a profound commentary on the endurance of art, the consuming nature of love and obsession, and the tragedy of lives caught in the crossfire of history, where loyalty and humanity are sacrificed for survival.

Thematic DNA

Identity, Gender, and Sexuality

The film's most central theme revolves around Cheng Dieyi's fluid identity. Forced into the female role of the concubine from a young age, the line between his stage persona and his true self dissolves. His famous line confusion, switching from "I am by nature a boy" to "I am by nature a girl," symbolizes this forced transformation and internal conflict. The film explores his deep, unrequited homosexual love for Xiaolou, a taboo subject handled with nuance, showing how his identity is inextricably linked to both his art and his suppressed desires in a society that does not accept him.

Art vs. Life

"Farewell My Concubine" constantly interrogates the relationship between performance and reality. For Dieyi, the opera is more real than life; he lives out the devotion of his character, Concubine Yu, wanting a lifetime of performance with his "King," Xiaolou. Xiaolou, in contrast, sees the opera as a profession, a means to a living, and is able to separate his roles from his off-stage life. This fundamental difference fuels their conflict. The film posits that in a world of constant chaos and betrayal, the structured, beautiful world of the opera can become a dangerous, all-consuming refuge.

Betrayal and Political Turmoil

The characters' personal betrayals are mirrored and amplified by the immense political shifts in China. The story moves through the Warlord Era, the Japanese invasion, and culminates in the Cultural Revolution, where individuals were forced to denounce loved ones to survive. The climax of this theme occurs during a struggle session where, under immense pressure, Xiaolou betrays Juxian and Dieyi, and Dieyi retaliates, leading to devastating consequences. It powerfully illustrates how political ideology can corrode the most profound human bonds of love and loyalty.

Tradition vs. Modernity

The Peking Opera itself represents China's rich cultural tradition. Throughout the film, this tradition is threatened by successive political regimes. The Japanese invaders demand performances, and later, the Communists dismiss the art form as feudalistic, replacing it with Maoist propaganda plays. The struggle of Dieyi and Xiaolou to maintain their art form becomes a metaphor for the struggle of Chinese culture to survive in the face of violent, imposed modernity and political extremism.

Character Analysis

Cheng Dieyi (Douzi)

Leslie Cheung

Motivation

Dieyi is driven by an all-consuming need for love and a desire for permanence, both of which he finds in the idealized world of the opera. His motivation is to live out a "lifetime" of performing "Farewell My Concubine" with Xiaolou, seeing their bond as sacred and unbreakable. He is obsessed with the idea of loyalty "from the beginning to the end."

Character Arc

Dieyi's arc is one of tragic convergence, where his identity completely merges with his art. Beginning as a timid boy forced to deny his male nature, he grows into a celebrated actor who finds his true self in the female role of Concubine Yu. His life becomes a quest to make reality conform to the opera's narrative of eternal devotion to his 'king,' Xiaolou. He remains steadfast in his artistic and personal loyalty through decades of turmoil, but Xiaolou's betrayals and the destruction of the opera world leave him with nothing. His final act is to make his life perfectly imitate his art, achieving a tragic, ultimate consummation.

Duan Xiaolou (Shitou)

Zhang Fengyi

Motivation

Xiaolou's primary motivation is survival. While he values his friendship with Dieyi and his love for Juxian, his actions are ultimately dictated by the need to navigate the treacherous political landscape. He wants to live a normal life, a desire that constantly clashes with Dieyi's artistic idealism and the brutal reality of their times.

Character Arc

Xiaolou begins as a strong, protective figure, the heroic "King" both on and off the stage. However, his arc is one of compromise and decline. Unlike Dieyi, he is a pragmatist who understands the need to adapt to survive. He separates his art from his life, marrying Juxian and seeking a conventional existence. As political pressures mount, his bravado erodes, revealing a cowardice that culminates in his public betrayal of both Dieyi and Juxian during the Cultural Revolution to save himself. By the end, he is a broken man, a "fake overlord" who has survived at the cost of his honor and his relationships.

Juxian

Gong Li

Motivation

Juxian's motivation is to escape her past and create a secure, conventional family life with Xiaolou. She fights to protect her husband and their relationship from Dieyi's influence and the dangers of the outside world. Her driving force is the simple but ultimately unattainable desire for safety and normalcy.

Character Arc

Juxian enters the story as a pragmatic and determined prostitute who cleverly secures her escape by marrying Xiaolou. She represents the world outside the opera—a world of tangible, earthly concerns. Her arc is a tragic struggle to build a normal life amidst the chaos. She is fiercely protective of Xiaolou and initially sees Dieyi as a rival, but she also shows moments of compassion towards him. Despite her strength and resilience, she is ultimately destroyed by the era's cruelty and Xiaolou's devastating betrayal, which shatters her dream of a simple, stable existence. Her suicide marks the final failure of life to triumph over art and ideology.

Symbols & Motifs

The Sword

The ornate sword symbolizes multiple concepts. Primarily, it represents the ideal of unwavering loyalty and the bond between the King and his Concubine in the opera. It embodies the pinnacle of artistic and personal devotion that Dieyi strives for. It also signifies masculinity, power, and, ultimately, the tragic finality of death, as seen in both the opera's and the film's climax.

The sword first appears when the boys admire it as apprentices. It later comes into the possession of the powerful patron, Master Yuan, who gifts it to Dieyi. Dieyi then gives it to Xiaolou as a wedding present, an act loaded with jealousy and meaning. Juxian later returns the sword to Dieyi just before her suicide. In the final scene, Dieyi uses the sword to take his own life, mirroring the actions of Concubine Yu and making his art and life one.

Peking Opera Makeup

The application of makeup is a ritual of transformation, symbolizing the blurring of identity between the actor and the role. For Dieyi, putting on the concubine's makeup is not just preparation for a performance but an act of becoming his true self. The bold, painted faces represent a world of art and order that contrasts sharply with the chaos and drabness of the real world, especially during the Cultural Revolution.

The film features numerous scenes of the actors meticulously applying their makeup. Dieyi's face, once painted, becomes a mask of feminine beauty and tragic devotion that he rarely takes off emotionally. During the Cultural Revolution, the actors are forced to remove their makeup and wear plain clothes, symbolizing the destruction of their art and identities. The final scene sees them applying the makeup one last time, a return to their shared world before the final tragedy.

The Sixth Finger

Douzi's (young Dieyi's) sixth finger represents a natural abnormality that prevents him from being accepted into the rigid, perfect world of the opera. Its brutal removal by his mother symbolizes a forced conformity and the first of many painful "castrations"—physical and psychological—that shape his identity and force him into his female role.

At the beginning of the film, Dieyi's mother, a prostitute, brings him to the opera school. The master refuses him because of his extra finger. In an act of desperate cruelty, his mother chops off the finger in the snow, allowing him to be accepted into the troupe. This violent act marks his definitive break from his past and the beginning of his painful journey into the world of performance.

Memorable Quotes

I am by nature a boy, not a girl.

— Cheng Dieyi (as a child)

Context:

As a young apprentice, Douzi repeatedly fails to recite the line correctly for the opera "Dreaming of a World Outside the Nunnery." After being brutally punished by his master, Shitou forces a pipe into his mouth, bloodying it, after which Douzi finally recites the line correctly, symbolizing a point of no return in the transformation of his identity.

Meaning:

This line, and Dieyi's struggle to say its opposite ("I am by nature a girl, not a boy"), is the psychological crux of the film. It represents the violent suppression of his innate identity and the forced adoption of a new one to fit his theatrical role. His eventual, tearful capitulation signifies the moment the line between self and performance begins to dissolve permanently.

I'm talking about a lifetime. One year, one month, one day, even one second's less makes it less than a lifetime.

— Cheng Dieyi

Context:

Dieyi says this to Xiaolou after they have become famous. Xiaolou has just announced his intention to marry Juxian, shattering Dieyi's fantasy that their on-stage partnership is a pact for life. This line is his desperate plea and a statement of his unwavering, if unrealistic, commitment.

Meaning:

This quote encapsulates Dieyi's philosophy of absolute devotion. He is not speaking merely of a professional partnership but of a lifelong, all-encompassing bond with Xiaolou, mirroring the undying loyalty of the concubine to her king. It highlights his idealistic, obsessive nature and his inability to separate his role from his reality.

You are really obsessed. Your obsession with the stage carries over into your everyday life. But how are we going to get through the days and make it in the real world among ordinary people?

— Duan Xiaolou

Context:

Xiaolou says this during one of their many arguments about Dieyi's intense jealousy over his relationship with Juxian. It is a moment of clear-sighted frustration, where Xiaolou points out the fundamental difference in how they perceive their lives and their profession.

Meaning:

This quote clearly articulates the central conflict between the two main characters. Xiaolou recognizes Dieyi's inability to distinguish between art and life, framing it as a dangerous obsession. It defines Xiaolou's pragmatism and his desire for a normal life, which stands in stark contrast to Dieyi's all-or-nothing idealism.

Philosophical Questions

Is identity inherent or is it a performance?

The film explores this question through Cheng Dieyi. From the moment his mother chops off his sixth finger to make him "fit" the opera school, his identity is shaped by external forces. He is brutally conditioned to embody a female role to the point where it consumes his sense of self. The film suggests that identity can be a fluid, constructed performance, yet it also shows that this performance has real, profound consequences on one's inner life and desires. Dieyi is most himself when he is performing as the concubine, blurring the very line between being and acting.

Can art survive in the face of totalitarian politics?

"Farewell My Concubine" charts the precarious existence of the Peking Opera through successive oppressive regimes. The art form is first co-opted by patrons and invaders, and later condemned and nearly eradicated by the Communists during the Cultural Revolution. Dieyi believes in the transcendent power of art, willing to perform for any audience. However, the film soberly concludes that art is not immune to politics. It can be suppressed, perverted into propaganda, and its practitioners can be broken. The final scene in the empty arena suggests that while the art form may have survived, its soul has been irrevocably damaged.

What is the cost of survival?

This question is primarily explored through Duan Xiaolou and Juxian. Both are pragmatists who make compromises to endure the horrific events they live through. Xiaolou's survival culminates in the ultimate compromise: betraying the people he loves most to save his own life. Juxian tries to survive by creating a small, private world away from politics, but it's not enough. The film argues that in times of extreme ideological fervor, the cost of survival can be one's own humanity, honor, and love, leaving the survivor as a hollow shell.

Alternative Interpretations

While the film's ending is tragic, its interpretation varies. One reading sees Dieyi's final act as the ultimate artistic statement: unable to live in a world that has destroyed his art and his love, he chooses to make his life perfectly and finally congruent with his art, achieving a form of tragic victory. It is the only way he can truly be the faithful concubine to the end.

Another interpretation views the ending as a complete tragedy of defeat. Dieyi's suicide is not a triumph but a final surrender to a lifetime of trauma, abuse, and heartbreak. In this view, he is not completing his art but is destroyed by his inability to ever separate from it, proving that such obsession is ultimately self-destructive in the real world.

A more political interpretation suggests the ending symbolizes the death of traditional Chinese culture itself. With the opera stage now in a sterile modern sports arena and its greatest performer dead, the film laments that the beauty and soul of this ancient art form cannot survive the brutalities of the 20th century and the new China that has emerged.

Cultural Impact

"Farewell My Concubine" had a monumental cultural impact both within China and internationally. Upon its release in 1993, it became the first Chinese-language film to win the prestigious Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, bringing unprecedented global attention to Chinese cinema. The film is a defining work of the Fifth Generation filmmakers, a group that explored the traumas of modern Chinese history with innovative and critical perspectives.

Its initial ban in mainland China, followed by a censored release due to international pressure, highlighted the ongoing tensions between artistic expression and state control under the Communist Party. The film's bold engagement with taboo subjects—particularly the sympathetic portrayal of a queer protagonist and a raw depiction of the chaos and brutality of the Cultural Revolution—sparked significant debate. For international audiences, it provided a sweeping, accessible, and deeply human lens through which to understand a tumultuous half-century of Chinese history. For many, the film is inseparable from the legacy of its star, Leslie Cheung, a queer icon whose tragic suicide in 2003 eerily echoed the fate of his character, cementing the film's status as a somber masterpiece about the relationship between an artist and their work.

Audience Reception

Audiences worldwide have overwhelmingly praised "Farewell My Concubine" as a masterpiece of epic storytelling and visual splendor. Viewers consistently laud the powerful and nuanced performance of Leslie Cheung as Cheng Dieyi, often cited as one of the greatest performances in cinema history. The film's emotional depth, the tragic love story, and its magnificent recreation of decades of Chinese history are frequently highlighted points of praise. The lavish costumes, detailed sets, and the mesmerizing depiction of the Peking Opera are also celebrated.

Criticism is minimal but sometimes points to the long runtime and the relentless tragedy, which can be emotionally exhausting for some viewers. A few scholarly critiques have debated its treatment of homosexuality, with some finding Dieyi's characterization to be a tragic queer stereotype, while others praise its boldness for the time. Despite these minor points, the general verdict from audiences is that it is a profound, unforgettable, and visually stunning film that offers a powerful human story against a grand historical canvas.

Interesting Facts

- The film was initially banned in China for its depiction of homosexuality, suicide, and the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution.

- Following international outcry and its win at Cannes, a censored version with 14 minutes cut was released in China.

- Leslie Cheung, who played Cheng Dieyi, was a native Cantonese speaker and not fluent in Mandarin. His lines were dubbed by the Beijing actor Yang Lixin, though Cheung's powerful non-verbal performance is celebrated.

- Director Chen Kaige had personal experience with the Cultural Revolution, having been a Red Guard who denounced his own father, a filmmaker. This experience lent authenticity to the film's portrayal of that era.

- "Farewell My Concubine" was the first and, to date, only Chinese-language film to win the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, an honor it shared with Jane Campion's "The Piano" in 1993.

- In a 2005 poll, the film was ranked as the most beloved film in Hong Kong.

- The film is considered a landmark of the "Fifth Generation" of Chinese filmmakers, who came to international prominence in the 1980s and 90s.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!