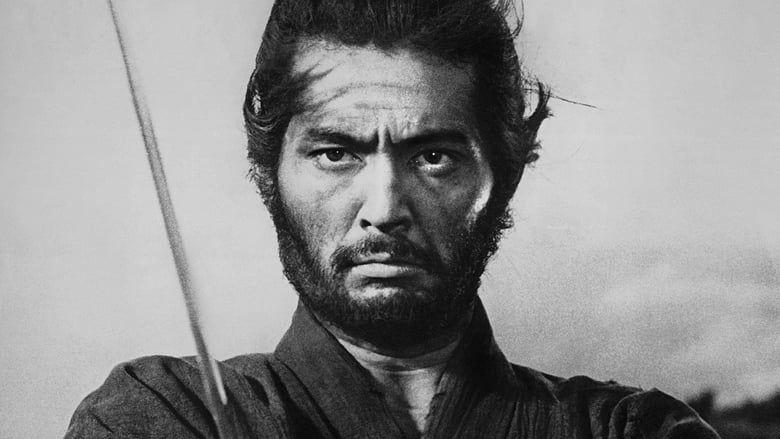

Harakiri

切腹

"What befalls others today, may be your own fate tomorrow."

Overview

Set in 17th-century Japan, "Harakiri" begins with an elder, masterless samurai named Hanshirō Tsugumo arriving at the estate of the powerful Iyi clan. He requests a dignified space in their courtyard to commit seppuku (ritual suicide), a fate he says he desires after a life of poverty and purposelessness. The clan's senior counselor, Saitō Kageyu, is suspicious of Tsugumo's motives, believing it to be a "suicide bluff" – a tactic used by desperate ronin to elicit sympathy and alms.

To deter him, Saitō recounts the grim story of another ronin, Motome Chijiiwa, who came with the same request a few months prior. The Iyi clan, determined to make an example of him, forced the destitute Motome to go through with the ritual using his bamboo practice sword, leading to an agonizing and humiliating death. Unfazed by the horrific tale, Tsugumo insists on proceeding. But before he begins, he asks for a moment to tell his own story, a narrative that slowly unravels the truth behind his request and exposes the cruel hypocrisy lurking beneath the clan's facade of honor.

Core Meaning

The core message of "Harakiri" is a powerful indictment of blind adherence to tradition and the hypocrisy of authoritarian power. Director Masaki Kobayashi uses the historical setting of the samurai era to critique the rigid social structures and inhumanity that can arise when codes of honor are valued more than human life and compassion. The film argues that true honor lies not in empty rituals and maintaining appearances, but in empathy, personal integrity, and fighting against injustice. It exposes how systems of power, like the Iyi clan, manipulate tradition to enforce control and preserve their reputation, even at the cost of profound cruelty. Ultimately, the film is a humanist plea, suggesting that individual dignity and family bonds are more sacred than any superficial code of conduct.

Thematic DNA

Hypocrisy of the Bushido Code

The central theme is the critique of the samurai code of honor, Bushido. The film portrays the Iyi clan as rigidly enforcing the code's rituals, like seppuku, not out of a sense of justice, but to maintain their reputation and authority. They punish Motome's desperate 'suicide bluff' with extreme cruelty, yet their own retainers, when faced with disgrace, choose to feign illness rather than commit suicide themselves. Hanshirō's systematic dismantling of their honor reveals that their adherence to Bushido is a facade, an instrument of oppression rather than a moral guide.

Critique of Authority and Power Structures

Director Masaki Kobayashi, a known pacifist and anti-authoritarian, uses the feudal Iyi clan as a metaphor for oppressive power structures in any era, including postwar Japan. The clan represents a soulless entity that prioritizes its own stability and image above all else. The story reveals how those in power manipulate history and truth, as seen in the final entry of the clan's official record, which erases Hanshirō's rebellion and frames the clan's actions as honorable. Hanshirō's individual rebellion is a direct challenge to this entrenched, unaccountable authority.

Humanism vs. Inhuman Tradition

The film creates a stark contrast between the desperate, loving actions of Hanshirō and his son-in-law Motome, and the cold, ritualistic cruelty of the Iyi clan. Motome sells his steel swords—the very soul of a samurai—to pay for his sick child's medicine, an act of profound love that the clan deems dishonorable. Hanshirō's quest is driven not by a desire for glory, but by love for his family and a need for justice for their suffering. The film champions these humanist values over the inhumanity of a code that forces a man to die in agony for being poor.

The Individual Against the System

Hanshirō Tsugumo embodies the struggle of an individual against a corrupt and unyielding system. He uses the system's own rules—the ritual of seppuku and the code of honor—to expose its moral bankruptcy from within. His methodical storytelling and eventual violent outburst represent a powerful act of defiance. Although he is ultimately killed and his actions are covered up, his rebellion leaves a crack in the facade of the clan's authority, symbolized by the lingering evidence of the severed topknot found after the cleanup.

Character Analysis

Tsugumo Hanshirō

Tatsuya Nakadai

Motivation

His primary motivation is not personal honor, but justice for the cruel, meaningless deaths of his son-in-law, Motome, his daughter, Miho, and his infant grandson, Kingo. He seeks to expose the inhumanity of the Iyi clan and make them account for their cruelty, using their own twisted code of honor against them.

Character Arc

Hanshirō begins as a seemingly defeated and destitute ronin, humbly requesting a place to die. Through his methodical storytelling, his true nature is revealed: he is an intelligent, patient, and deeply grieving man on a quest for justice, not honor. His initial calm transforms into righteous fury as he systematically exposes the Iyi clan's hypocrisy, moving from a passive storyteller to an active, avenging warrior who challenges the very foundations of the samurai code.

Saitō Kageyu

Rentarō Mikuni

Motivation

Saitō's sole motivation is the preservation of the Iyi clan's power, reputation, and honor at any cost. He is the enforcer of the rigid, unfeeling code, believing that any sign of leniency would make the clan appear weak. His actions are dictated by the need to maintain appearances and uphold the status quo.

Character Arc

Saitō starts as a calm, authoritative figure, confident in his clan's power and the righteousness of their strict adherence to Bushido. He is condescending and suspicious of Hanshirō. As Hanshirō's story unfolds, Saitō's composure cracks, revealing his deep-seated arrogance and concern for reputation over truth. By the end, he is exposed as a hypocrite, forced to orchestrate a massive cover-up to preserve the clan's tarnished image, embodying the film's critique of hollow authority.

Chijiiwa Motome

Akira Ishihama

Motivation

Motome's motivation was simple and pure: to get money to pay for a doctor for his critically ill wife and son. His 'suicide bluff' was a desperate, last-ditch effort to save his family, showing that he valued their lives over the abstract concept of his own samurai honor.

Character Arc

Motome's story is told entirely through flashbacks. Initially presented by Saitō as a dishonorable coward trying to exploit the 'suicide bluff', he is later revealed by Hanshirō to be a loving husband and father driven to desperation by poverty and sickness. His arc is a tragic recontextualization, transforming him from a cautionary tale of disgrace into a symbol of humanism crushed by a merciless system.

Symbols & Motifs

The Empty Suit of Armor

The ancestral armor of the Iyi clan symbolizes their hollow, superficial, and ultimately empty concept of honor. It represents the clan's glorious past and the rigid traditions they claim to uphold, but like the armor itself, this honor is devoid of any real humanity or substance.

The armor is shown prominently at the beginning and end of the film. During his final battle, Hanshirō contemptuously smashes the armor, symbolically destroying the clan's false honor and exposing its emptiness. The clan later restores it, signifying their commitment to perpetuating the lie and maintaining the facade of their authority.

The Bamboo Sword

Motome's bamboo sword is a powerful symbol of his poverty and the cruel inflexibility of the Bushido code. A samurai's steel sword was considered his soul, and by selling his, Motome prioritized his family's survival over this symbolic honor. The bamboo blade represents the tragic clash between human necessity and rigid, impractical tradition.

Saitō recounts how Motome, having sold his real blades to feed his family, was forced by the Iyi clan to perform seppuku with his blunt bamboo sword. This act turns a ritual of honor into a prolonged, gruesome torture, underscoring the clan's sadism and the tragic consequences of their so-called principles.

The Severed Topknot

For a samurai, the topknot was a symbol of status and honor, as essential as his sword. To have it cut off was a profound humiliation, a fate considered by some to be worse than death.

Before arriving at the Iyi estate, Hanshirō tracks down the three samurai responsible for his son-in-law's death and cuts off their topknots, a subtle and deeply personal form of revenge. He reveals the topknots in the courtyard, proving their cowardice and shattering the clan's image of martial prowess. A single topknot found by a cleaner at the end serves as the only remaining physical evidence of the true, officially erased events.

Memorable Quotes

After all, this thing we call samurai honor is ultimately nothing but a facade.

— Hanshiro Tsugumo

Context:

Spoken in the courtyard of the Iyi estate after he has revealed the truth about Motome and presented the severed topknots of the clan's three samurai. It is his final, damning verdict on their entire value system before the final battle ensues.

Meaning:

This line encapsulates the film's central thesis. Hanshirō speaks it after systematically proving that the Iyi clan's adherence to the Bushido code is not about true integrity but about maintaining appearances and power. It's a direct condemnation of the hypocrisy he has exposed.

What befalls others today, may be your own fate tomorrow.

— Hanshiro Tsugumo

Context:

Hanshirō says this to Saitō and the assembled samurai early in his narrative, framing his personal story as a universal cautionary tale. It sets a tone of foreboding and philosophical weight for the revelations to come.

Meaning:

This is a warning from Hanshirō to the comfortable and arrogant Iyi clan members. He reminds them that their privileged position is not guaranteed and that the suffering they inflict on the less fortunate could easily become their own reality, highlighting the fickle nature of fate and the arrogance of power.

A samurai's sword is his soul.

— Saitō Kageyu (paraphrasing the samurai ideal)

Context:

This ideal is articulated by the Iyi clan members to justify their contempt for Motome, who pawned his swords. They see his action as the ultimate disgrace, failing to understand the desperate, humane reasons behind it.

Meaning:

This quote represents the rigid, traditionalist view of the samurai class. It signifies that a samurai's identity and honor are inextricably linked to his weapons. The film proceeds to deconstruct this idea, suggesting that a man's soul truly resides in his compassion and love for his family.

Philosophical Questions

What is the nature of true honor?

The film relentlessly questions whether honor is an external code imposed by society or an internal moral compass. The Iyi clan represents external honor—obsessed with reputation, ritual, and saving face. Hanshirō and Motome represent internal honor—defined by love, sacrifice, and personal integrity. The film forces the viewer to confront the brutal consequences of prioritizing the former over the latter, suggesting that true honor is inseparable from humanity and compassion.

Can an individual successfully challenge a corrupt system?

"Harakiri" offers a cynical yet complex answer. Hanshirō succeeds in his goal of exposing the Iyi clan's hypocrisy to their faces and achieving personal vengeance. He dismantles their honor within the confines of their own courtyard. However, the system ultimately prevails. He is killed, and the official records are rewritten to erase his defiance, preserving the clan's reputation. The final shot of a cleaner finding a severed topknot suggests that the truth, while officially buried, can never be completely erased, leaving a lingering, ambiguous statement on the efficacy of individual rebellion.

Is tradition a source of moral guidance or a tool of oppression?

The film portrays tradition, specifically the Bushido code, as a tool of oppression. The Iyi clan weaponizes tradition to justify their cruelty towards Motome and to maintain their rigid hierarchy. Kobayashi suggests that when traditions are followed without question or compassion, they lose their moral authority and become instruments for the powerful to control the weak. Hanshirō's rebellion is a fight against the tyranny of unthinking, inhuman tradition.

Alternative Interpretations

While the dominant interpretation of "Harakiri" is a straightforward critique of feudal hypocrisy, some analysis points to a deeper, more tragic reading of Hanshirō's final actions. After spending the entire film exposing the samurai code as a hollow facade, Hanshirō attempts to commit seppuku in his final moments before being shot. This act can be interpreted not as a final victory, but as the ultimate tragedy: even a man who sees through the system's lies cannot fully escape its ideological grip. In this view, Hanshirō's final gesture suggests that the corrosive power of such traditions is so deeply ingrained that even its most ardent critic remains bound by its rituals in death.

Another perspective focuses less on the historical critique and more on the film's universal, existentialist themes. Hanshirō's journey can be seen as that of an individual creating his own meaning and morality in a meaningless, absurd world. Stripped of his status, family, and purpose, he rejects the socially prescribed code of honor and forges his own path of justice. His final stand is less about samurai tradition and more about an individual's ultimate, defiant assertion of his own humanity against an oppressive and indifferent universe.

Cultural Impact

"Harakiri" was released in 1962, a period of significant social and economic change in post-war Japan. Director Masaki Kobayashi used the jidaigeki (period drama) genre as a vehicle to comment on contemporary issues, a common practice for dissident filmmakers of the era. By setting the story in the 17th century, a time of peace when the samurai class was becoming obsolete, he drew a parallel to Japan's post-WWII identity crisis and critiqued the lingering feudal and militaristic ideologies he saw in modern Japanese society, such as in the corporate zaibatsu structures.

Critically, the film was hailed as a masterpiece for its powerful narrative, stunning visual composition, and thematic depth. It stood in stark contrast to many samurai films of the time that glorified the warrior code. "Harakiri" dismantled it, portraying it as a rigid, inhuman system used by the powerful to oppress the weak. Its unflinching critique of authority and hypocrisy resonated internationally and continues to influence filmmakers today. Roger Ebert included it in his "Great Movies" list, praising its ethical complexity and masterful storytelling. The film's influence can be seen in its deconstruction of genre tropes and its use of a nonlinear narrative to build suspense and reframe the audience's understanding of events, a technique that has been echoed in many later films.

Audience Reception

Audience reception for "Harakiri" has been overwhelmingly positive since its release, and it is widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made. Viewers consistently praise its masterful storytelling, which uses a non-linear, puzzle-like structure to slowly reveal the truth and build immense tension and emotional weight. The performance of Tatsuya Nakadai as Hanshirō Tsugumo is frequently singled out as legendary, conveying a profound depth of grief, intelligence, and simmering rage. The film's stark, beautiful black-and-white cinematography and its powerful thematic critique of hypocrisy and authority are also major points of acclaim. The most common point of criticism, if any, is directed at the film's deliberate, slow pacing, which some viewers may find challenging. The gruesome scene of Motome's seppuku with the bamboo sword is often cited as a controversial and deeply disturbing moment, yet it is also recognized as essential to the film's powerful anti-authoritarian message. The overall verdict is that "Harakiri" is a poignant, intelligent, and emotionally devastating masterpiece that transcends the samurai genre.

Interesting Facts

- Director Masaki Kobayashi was a pacifist who was drafted into the Imperial Japanese Army during WWII. He consistently refused promotion above the rank of private as a protest against the war. His anti-authoritarian and anti-militarist views heavily influence the themes of the film.

- Tatsuya Nakadai, who gives an iconic performance as the world-weary Hanshirō, was only 29 years old during the filming of "Harakiri".

- The screenplay was written by Shinobu Hashimoto, who was a frequent collaborator with Akira Kurosawa, having penned the scripts for legendary films like "Rashomon" and "Seven Samurai".

- The film won the Special Jury Prize at the 1963 Cannes Film Festival.

- "Harakiri" is often cited as one of the greatest 'anti-samurai' films ever made because, while it uses the genre's setting, it actively subverts and critiques the glorification of the samurai class and its code.

- The film's original Japanese title is "Seppuku," which is the more formal, Sino-Japanese term for the ritual suicide. "Harakiri," literally "belly-cutting," is the native Japanese term and was more commonly used by Westerners.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!