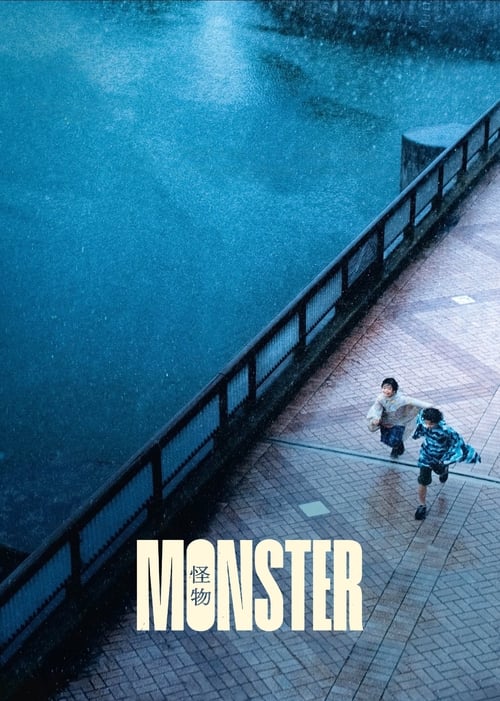

Monster

怪物

"Are they the ones we dream of, or the ones we fail to see among us?"

Overview

"Monster" tells the story of Minato, a young boy whose increasingly strange behavior alarms his single mother, Saori. Believing his teacher, Mr. Hori, is the cause, she confronts the school, only to be met with bureaucratic indifference.

The film masterfully unfolds through three different perspectives: Saori's, Mr. Hori's, and finally, Minato's. Each viewpoint reframes the events, challenging the audience's initial judgments and gradually revealing a more complex and heart-wrenching truth. The narrative peels back layers of misunderstanding, bullying, and societal pressure to expose the profound connection between Minato and his classmate, Yori.

Core Meaning

"Monster" explores the profound and often damaging gap in understanding between the world of adults and the world of children. The film posits that the true 'monster' is not a person but rather the societal pressures, preconceived notions, and rush to judgment that create misunderstanding and suffering. Director Hirokazu Kore-eda and screenwriter Yuji Sakamoto suggest that it is the adult world's rigid definitions of normalcy, particularly concerning masculinity, that persecute the children. It is a moving damnation of the effects of shame and a call for empathy, urging viewers to look beyond surface appearances and listen to the truths that children often cannot articulate.

Thematic DNA

The Subjectivity of Truth

The film is structured in a Rashomon-like manner, presenting the same sequence of events from three distinct viewpoints. This narrative technique forces the audience to constantly re-evaluate their understanding of the characters and the situation. What initially appears to be a clear case of teacher abuse is complicated and ultimately subverted as more perspectives are revealed, highlighting how personal biases and incomplete information shape our perception of reality. The film shows that 'truth' is often multifaceted and that jumping to conclusions based on limited information is where the real monstrosity lies.

Childhood Innocence and Secrecy

At its core, "Monster" is a sensitive portrayal of childhood and the secret worlds children create to navigate their feelings and escape the pressures of the adult world. Minato and Yori's bond, and their private sanctuary in an abandoned train car, represents a space free from judgment. The film explores how children hide their deepest struggles, insecurities, and emerging identities from adults who they believe won't understand. It captures the pain of being misunderstood and the desperate longing for acceptance.

Societal Pressure and Non-Conformity

The film critically examines the damage caused by societal norms and expectations. Yori is bullied for his perceived effeminate behavior, and his abusive father tries to violently "cure" him. Minato struggles with his feelings for Yori, internalizing the idea that he might be a "monster" for not conforming to traditional ideas of masculinity. The 'monster' of the title refers to this societal pressure to conform, which alienates and harms those who are different.

Miscommunication and Judgment

A central conflict in the film arises from the complete breakdown of communication between the adults. Saori's legitimate concerns are met with the school's defensive and disingenuous bureaucracy. Rumors and hearsay are weaponized, leading to false accusations and ruined reputations. The film demonstrates how quickly people form harsh judgments based on superficial information, becoming 'monsters' in their ignorance and lack of empathy.

Character Analysis

Minato Mugino

Soya Kurokawa

Motivation

His primary motivation is to understand and accept his feelings for Yori while navigating the fear of being seen as different or 'monstrous' by society, his peers, and even himself. He longs for a space where his friendship with Yori can exist without shame.

Character Arc

Minato begins as a quiet, withdrawn boy exhibiting confusing behavior. He is torn between his genuine feelings for Yori and the societal pressure to conform, which leads him to act harshly towards Yori in public. He internalizes the idea that he might be a 'monster'. His journey is one of self-acceptance, culminating in his decision to run away with Yori, choosing their bond over the judgment of the outside world.

Yori Hoshikawa

Hinata Hiiragi

Motivation

Yori is motivated by his deep need for connection and acceptance. His friendship with Minato is his lifeline, providing the love and understanding he is denied everywhere else. He seeks to protect their shared world from the cruelty of others.

Character Arc

Yori is openly bullied by classmates for his gentle and perceived 'effeminate' nature and is abused by his alcoholic father at home. Despite the cruelty he faces, he remains open-hearted and deeply attached to Minato. His arc is about finding solace and acceptance in his friendship with Minato, which becomes his only refuge from a hostile world.

Saori Mugino

Sakura Ando

Motivation

Driven by a powerful maternal instinct, Saori's sole motivation is to protect her son, Minato. She is determined to find the source of his pain and hold someone accountable, but her focused pursuit initially blinds her to the deeper truth of his situation.

Character Arc

Saori starts as a fiercely protective mother convinced her son is a victim of abuse by his teacher. She aggressively pursues what she believes is justice, inadvertently contributing to the escalating misunderstandings. Her perspective shifts dramatically as she learns more, moving from certainty to confusion and finally to a dawning, painful realization of the true, complex situation. Her arc is about learning the limits of her own perception and the difficulty of truly understanding her child's inner world.

Michitoshi Hori

Eita Nagayama

Motivation

Initially, Hori is motivated to be a good teacher. When accused, his motivation shifts to defending his reputation and proving his innocence. Ultimately, his empathy and lingering sense of responsibility drive him to understand what is truly happening with Minato and Yori.

Character Arc

Mr. Hori is initially presented as the titular 'monster', a potentially abusive teacher. However, from his perspective, he is a well-intentioned but flawed educator who becomes the victim of a vicious misunderstanding fueled by rumors and a defensive school administration. His life is nearly destroyed by the false accusations. His arc involves moving from a confident teacher to a social pariah, and finally to someone who begins to piece together the truth about the boys' relationship.

Makiko Fushimi

Yuko Tanaka

Motivation

Her primary motivation seems to be protecting the institution of the school at all costs, adhering to protocol over genuine engagement. However, her actions are also deeply colored by her own suppressed grief and a belief that some truths cannot be easily told or understood.

Character Arc

The school principal, Fushimi, appears as a cold, indifferent bureaucrat, offering disingenuous apologies while protecting the school's reputation. She is frustratingly opaque. However, a late-film revelation about a personal tragedy—the loss of her own grandchild—re-contextualizes her behavior. Her arc is a subtle one, from an apparent antagonist to a figure of quiet, unresolved grief, who ultimately shows a moment of empathy and understanding to Minato.

Symbols & Motifs

The Abandoned Train Car

The train car symbolizes a sanctuary and a private world for Minato and Yori. It is a space of freedom and acceptance, away from the confusing and judgmental eyes of classmates and adults, where they can be their true selves without fear.

The boys find and decorate the abandoned train car in a secluded railway tunnel. It becomes their secret base, the only place where their bond can flourish. They share moments of intimacy and vulnerability there, starkly contrasting with their tense interactions at school.

Fire and Storm

The film opens with a building fire and culminates in a typhoon. These elements symbolize destruction and renewal. The fire acts as a catalyst, bringing underlying tensions to the surface, while the storm washes away misunderstandings and falsehoods, ultimately leading to a form of rebirth or liberation for the boys.

The fire at the hostess bar is the backdrop for the initial events and is revisited from each perspective. The torrential typhoon occurs during the film's climax, creating a sense of crisis that forces confrontations and ultimately leads to the boys' escape into a sun-drenched, renewed world.

The French Horn and Trombone

The sounds of the French horn and trombone played by the boys represent their non-verbal communication and the expression of their true feelings, which they cannot articulate in words. The music is a pure, honest form of connection that transcends the misunderstandings of spoken language.

Minato and Yori sneak into the school's music room to play their instruments. In a key scene, they play them loudly out of the window, a cathartic release of their pent-up emotions and a way of communicating their shared experience to a world that doesn't listen.

"Pig's Brain"

The phrase "pig's brain" symbolizes internalized homophobia and the fear of being abnormal or monstrous. It originates from Yori's abusive father, who uses it to denigrate his son. Yori, and subsequently Minato, grapple with this insult, fearing that their feelings for each other make them less than human.

Minato unsettlingly asks his mother if he'd still be human with a pig's brain transplant at the beginning of the film. This is initially misinterpreted by the adults. The truth is later revealed: Yori's father claims his son has a pig's brain, a slur that Minato internalizes due to his closeness with Yori.

Memorable Quotes

怪物だーれだ?

— Minato Mugino / Yori Hoshikawa

Context:

This phrase is chanted by Minato early in the film, which his mother overhears and interprets as a sign of his distress. The question echoes throughout the narrative as each new perspective shifts the blame and complicates the notion of monstrosity.

Meaning:

Translating to "Who's the monster?", this recurring question is the central query of the film. It's not a literal question but a philosophical one, forcing characters and the audience to question who the real monster is: the accused teacher, the bullies, the abusive parent, the indifferent system, or perhaps the act of judgment itself.

Some truths cannot be told because there is no one who will listen and understand.

— Makiko Fushimi (Principal)

Context:

The principal says this to Minato in a quiet, vulnerable moment near the end of the film. Having just confessed a secret of her own (that she lied about hitting a child in a supermarket), she connects with Minato's inability to articulate his own struggles, showing a surprising moment of empathy.

Meaning:

This statement from the principal encapsulates a core theme of the film: the profound difficulty of communicating one's deepest, most vulnerable truths in a world that is not prepared or willing to hear them. It speaks to the boys' secret world and her own hidden grief, suggesting that silence is sometimes a form of self-preservation against inevitable misunderstanding.

Philosophical Questions

Who is the real 'monster'?

The film relentlessly poses this question, shifting the audience's suspicions with each new perspective. It challenges the very idea of a singular monster, suggesting instead that monstrosity is a product of circumstance, misunderstanding, and societal failure. Is it the abusive father? The rigidly bureaucratic school staff? The mother who makes false accusations in her desperation? Or is it the intangible pressure of social norms that forces children to hide their true selves? Ultimately, the film suggests the 'monster' is the collective failure of empathy and the act of judging others without understanding their full story.

Can truth be perceived from a single viewpoint?

Through its narrative structure, "Monster" argues that objective truth exists, but it cannot be grasped from a single, subjective perspective. Each character holds a piece of the truth, but their personal biases, emotions, and limited information create a distorted picture. Saori sees an abuser, Hori sees a bully, and only when the audience sees through the children's eyes do the pieces assemble into a coherent, heartbreaking whole. The film is an exercise in epistemology, exploring how we come to know things and the dangers of certainty in a complex world.

What is the nature of humanity when stripped of societal labels?

At the beginning of the film, Minato asks his mother if a person is still themselves if their brain is replaced with a pig's. This question frames the film's exploration of identity. The boys' sanctuary in the abandoned train is a space outside of society where they can simply 'be'. The film contrasts the adults, who are defined by their roles and social obligations, with the children, who are grappling with their fundamental sense of self. It questions what it means to be human when faced with labels like 'bully', 'victim', or 'monster', suggesting that true humanity lies in the capacity for connection and love, as exemplified by the boys' pure, un-categorizable bond.

Alternative Interpretations

The most debated aspect of "Monster" is its ending. After the typhoon, Minato and Yori emerge from their sanctuary into a sun-drenched landscape, running freely and laughing. This has led to two primary interpretations:

- A Hopeful, Metaphorical Rebirth: This reading sees the ending as a symbolic liberation. The children have weathered the storm of misunderstanding and societal judgment and have emerged into a new reality where they are free to be themselves. They are not literally dead or reborn, but they have been 'reborn' into a state of self-acceptance. The broken fence symbolizes the removal of the obstacles that previously trapped them. Director Hirokazu Kore-eda himself has described the final scene as a "blessing" and a "celebration" for the boys, freeing themselves from societal pressures.

- A Tragic, Afterlife Fantasy: Another, more somber interpretation suggests that the boys did not survive the typhoon and the subsequent mudslide that buried their hideout. The final sequence is seen as a depiction of their spirits in the afterlife, a beautiful and peaceful fantasy where they can finally be together without pain. The heavenly light, their dialogue about being 'reborn', and the fact that the adults cannot find them support this tragic reading.

The director has stated he left the ending intentionally ambiguous, wanting it to be both a cautionary tale for adults and a message of hope for children.

Cultural Impact

"Monster" was met with widespread critical acclaim upon its release, praised for its masterful screenplay, sensitive direction, and powerful performances, particularly from the young actors. It continued director Hirokazu Kore-eda's international recognition as a master of humanist cinema. The film's use of a multi-perspective narrative drew frequent comparisons to Akira Kurosawa's classic "Rashomon," but critics noted that "Monster" uses the structure not to question the existence of objective truth, but to build empathy by gradually revealing a complete, albeit complex, reality.

The film resonated deeply for its compassionate and nuanced exploration of queer themes within a childhood context, a topic often sensitively handled in Japanese cinema. It addresses issues of bullying, family dysfunction, and the failures of educational systems with a quiet intensity that sparked conversations about societal pressures on children. Ryuichi Sakamoto's final, poignant score also drew significant attention, adding a layer of melancholic beauty that became inseparable from the film's emotional impact. "Monster" is considered a significant work in contemporary Japanese cinema for its complex storytelling and its gentle yet firm critique of a society that can inadvertently create 'monsters' through prejudice and misunderstanding.

Audience Reception

Audiences have largely praised "Monster" for its powerful emotional impact, intricate storytelling, and exceptional performances. Many viewers found the film deeply moving, often to the point of tears, and lauded its ability to build empathy for every character, even those who initially seem antagonistic. The screenplay by Yuji Sakamoto is frequently cited as a masterpiece of structure, with audiences appreciating how the shifting perspectives slowly and masterfully reveal the heartbreaking truth.

The main point of discussion and mild criticism revolves around the film's deliberate pacing and ambiguity, particularly its ending. While many found the open-ended conclusion beautiful and thought-provoking, some viewers expressed frustration, desiring a more definitive resolution. The film's sensitive handling of its queer coming-of-age story was widely celebrated as poignant and respectful. Overall, audiences see it as a profoundly human and unforgettable cinematic experience that lingers long after the credits roll.

Interesting Facts

- This was the final film scored by the legendary composer Ryuichi Sakamoto, who passed away two months before the film's premiere. The film is dedicated to his memory.

- "Monster" marks the first time since his 1995 debut, "Maborosi," that director Hirokazu Kore-eda has directed a screenplay he did not write himself. The script was written by Yuji Sakamoto.

- The film won the Best Screenplay award and the Queer Palm at the 76th Cannes Film Festival in 2023.

- Director Hirokazu Kore-eda intentionally made the ending ambiguous to evoke a sense of fear in adults that they might be too late to understand their children, while also offering hope to young viewers that they can find happiness with courage.

- The film's Japanese title, "Kaibutsu" (怪物), refers to a physical, terrestrial creature, as opposed to "obake," which is more spectral like a ghost.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!